Patrick Finegan was born during the latter half of the Eisenhower Administration and graduated during the Carter and Reagan Administrations from Northwestern University and the University of Chicago Law School and Graduate School of Business. He worked more than thirty years in law, corporate finance, management consulting and risk management. He has a wife and grown daughter and has lived in the New York metropolitan area his entire professional life – most of it in the same residential cooperative. Cooperative Lives is his first work of fiction.

Patrick Finegan was born during the latter half of the Eisenhower Administration and graduated during the Carter and Reagan Administrations from Northwestern University and the University of Chicago Law School and Graduate School of Business. He worked more than thirty years in law, corporate finance, management consulting and risk management. He has a wife and grown daughter and has lived in the New York metropolitan area his entire professional life – most of it in the same residential cooperative. Cooperative Lives is his first work of fiction.

Tell us about your book.

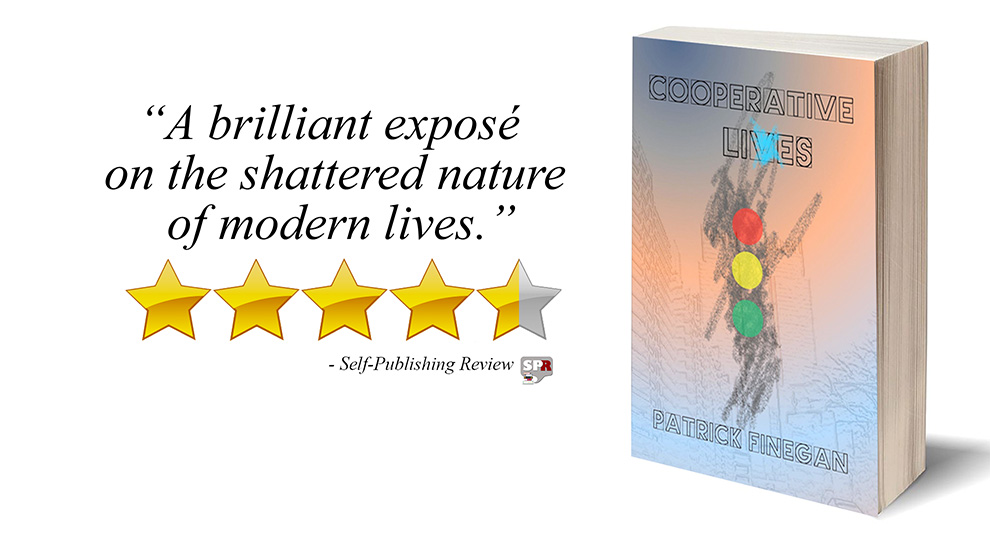

Cooperative Lives centers on two middle-aged, multi-racial Manhattan families – their professional and interpersonal misadventures and their considerably older and whiter neighbors. The events take place from 2010-13 in and around a staid 300-unit cooperative overlooking Central Park, where a minor traffic accident triggers a series of increasingly bizarre financial and intelligence investigations that expose the residents’ largely separate lives to unrelenting media scrutiny. Cooperative Lives is a novel about the fragility and resilience of bonds – between family members, co-workers, lovers and neighbors – when tested by illness, differences of class, race, religion and age, seemingly trivial misjudgments, and unwelcome outside attention. It was written post-9/11 but before the 2016 election in a world not yet untethered by rampant nationalism.

Why did you want to write a book?

Writing a book did not rank high on my “to do” list. I’d spent thirty years in corporate finance, law and risk management, authoring research articles for Corporate Finance Review and The Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, and opinion pieces for business magazines and newspapers. But a book, much less a novel? I considered it too time-consuming, too far afield, too unremunerative. A series of medical adventures and the financial crisis and softened my perspective. Unemployment granted me vast tracts of idle time and the medical adventures enunciated their significance. If I yearned to leave anything of literary value behind, those tracts of otherwise idle time were precious.

I chose an easy first subject: two fictionalized neighbors – a happy diversion from the frustration of applying for an occasional mid-management job opening with a specialized, senior-level résumé. I thought the short stories were good. So I wrote a couple more, drawing copiously from my medical, personal and professional ups and downs. Because inventing a new set of neighbors for each short story grew tiresome, I began to reuse them. Ties between those characters evolved subconsciously, eventually unfolding into a novel. Seven years later, I readied the manuscript for publication.

Why did you choose to self-publish?

Why did you choose to self-publish?

Necessity. I didn’t know any agents, established fiction authors, or fiction publishers personally in 2013 and still do not. Instead, I circulated the initial manuscript to friends who were journalists, academics and PR editors, hoping for feedback and advice. Alas, I received just one acknowledgement of even receipt. Crestfallen, I set the manuscript aside. I revisited the manuscript last Christmas and thought, as I did in 2013, that it merited publication. I resolved, one way or another, to publish it before my sixtieth birthday.

Thankfully, the world of self-publishing has evolved. Amazon is now brimming with best-selling self-published authors. The royalties are better, the timetables are better. What’s missing is the marketing muscle. But widespread sales were never my goal. Critical acceptance was, so self-publishing seemed just fine. It also met my timeline. I released the book on Kindle one week before my birthday.

What tools or companies did you use, and what experience did you have?

To write the book: Microsoft proofing tools and a desktop thesaurus. The initial manuscript took me seven months, five-to-ten hours per day. The pre-publication revisions took me four months, so nearly a year of writing, rewriting and editing.

To publish the book: Formatting the manuscript into kdp, epub and paperback- and hardcover-suitable pdfs was an adventure, made possible by Microsoft Word, an open-source text/HTML editor (Notepad++), and Kindle Direct Publishing’s Kindle Create applet. It took hours to assign standardized styles to each paragraph of the manuscript (they were originally double-spaced Times Roman), but once I had, reformatting the manuscript for each online and print version was easy. Pagination was tricky because certain pages, e.g., section dividers and prefatory material, are supposed to remain unnumbered. I resorted to covering them with white rectangles. One consternation I had was with embedded images or diagrams. Because KDP and ePub do not accept png files, backgrounds cannot be transparent. So the default background for my embedded images was white, which worked fine until a Kindle user elected to read my book in sepia or white-on-black. Then the images looked goofy. I used IngramSpark to produce hardcover copies of my book and reach non-Amazon sales channels. Paper stock and print quality were outstanding.

To market the book: I reached out to book editors at several newspapers and magazines but failed to elicit interest, so I submitted it to “sponsored review” programs at Kirkus, Blue Ink, Foreword/Clarion, Indie Reader, Reedsy Discovery and, of course, Self-Publishing Review. My general impression was that the thoroughness, insightfulness and accuracy of the review was inversely proportional to the amount paid. The upstarts work hard for their money; the more established players can be lazy.

What tips can you give other authors looking to self-publish?

Tip One: Apply for your Library of Congress preassigned control number (PCN) before you publish. I know from experience that it is nearly impossible to obtain afterward.

Tip Two: Hire an editor plus one or two beta readers. It will cost you $7,000 to $12,000, you’ll have to rewrite much more, and your publication schedule will stretch out 2-3 months farther, but you won’t regret, as I do, that certain passages dragged on too long or were too divergent. Once committed to paper, I fell in love with my words. Extirpating them, much less rewriting whole sections, was anathema. I had a friend and playwright who graciously ripped apart my first four chapters. With his observations as guidance, I attempted to apply a similar level of objective criticism to the 25 chapters that followed. I succeeded only partially. Had I retained an editor, the book would have been much tighter.

Tip Three: Hire a cover artist. I’m a cheapskate. I designed my own cover and remain happy with the creation. But the title doesn’t leap from the page as others do and the graphics don’t glisten. In 1980, the cover would have been eye-grabbing. But the technology has evolved. To compete for shelf attention today, it is wise to hire a professional.

Tell us about the genre you wrote in, and why you chose to write this sort of book.

Borderline historical fiction, possibly literary fiction. Cooperative Lives takes place from 2010-13 but the backstories transpire during NYC’s “go go” 80s and 90s. I sought to represent the epoch as richly as possible, so that the contemporary characters and plot twists were more plausible and more visceral. Ironically, even my description of 2013 seems nostalgic today. The political and economic landscape has changed so much. So definitely: borderline historical fiction. As a first-time author, I considered it prudent to write about familiar subjects. I had 30 years’ experience in law and corporate finance, 25 years’ marital experience, 20 years’ experience in the same residential cooperative, 15 years’ experience as a dad, an abiding love for skiing and skating, and a lifetime’s share of healthcare misadventures. What I lacked was any fiber of derring-do, ability to conjure up fantasy realms, real-life detective experience, or interest in steamy romance. So the remaining options were general fiction, literary fiction and historical fiction. I chose a blend of all three.

Who are your biggest writing inspirations and why?

My biggest literary inspirations are regrettably dated. My favorite novel remains Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence. But I also love the satire and richness of Anthony Trollope, the copious detail of Charles Dickens, the droll commentary of Henry James, the clarity of Somerset Maugham, and the poetic simplicity of Thomas Hardy. There are of course dozens of contemporary writers who blow me away with their craft. Eleanor Catton’s The Luminaries, Richard Powers’ The Overstory, Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See are nearly perfect. Today’s talent pool is just extraordinary. And not just here. The Internet and personal computer have made writing easier, more international and, in my opinion, more engaging. The future of the industry is bright.

How do your friends and family get involved with your writing? What do they think of your book?

Cooperative Lives remained secret until the first draft was nearly complete. I’d toiled in law, corporate finance and risk management for nearly thirty years but, like many of my peers, found myself adrift during and after the financial crisis. The book began as a diversion, a couple fictional accounts about my neighbors. I typed furiously at my desk behind the sofa for seven months. My wife and daughter assumed I was writing articles about applied corporate finance, perhaps even a treatise, but certainly not a novel. They were concerned, evidently more than I was, with how we were going to pay the bills. Until it was published, only three friends acknowledged perusing the manuscript (I sent it to dozens). Two were pen pals from Germany and Austria. They read it cover-to-cover and loved it. The third was a former law school classmate and present-day playwright who cut my first four chapters to shreds. I would never have published the book without their insight and support. Once published, the book surprised everyone, especially my family. No, they still haven’t read it.

How can someone afford to take up writing mid-career?

In most instances, I don’t think it’s possible, not without deep pockets, an absence of dependents, or a generous partner or spouse. Writing is extraordinarily expensive, not of course the pen and ink, but the opportunity cost. Research the New York Times’ bestseller list and nearly every author studied writing in college or began writing shortly thereafter. They forged their lifestyles, relationships, financial obligations and expectations around the often-meager prospects of their profession. Now consider someone who has been gainfully employed in an office or factory for thirty years, someone with a family, a mortgage, staggering insurance premiums, and impending college tuition costs.

There is no logical way to explain to friends, loved ones or even yourself how or why you plan to become a writer. I didn’t bother; I chose secrecy. But I had the good fortune of having only two dependents, of having repaid my mortgage, of not owning a car, and of having squirreled away enough to retire. Writing a novel is a full-time endeavor. There are perhaps writers who can devote an hour here, an hour there, and produce something meaningful. But they aren’t neophytes; they aren’t mid-career literary first timers. There is no shortage of budding writers post-retirement, just as there is no shortage of authors who began writing in college or shortly thereafter. But first-time authors in their forties and fifties, ones with personal insight into the world in which they actually worked? It’s a bit of a vacuum, a vacuum I’m trying to fill. I hope there are others who are as fortunate.

What are your plans now your book is published?

Collect fodder for a stand-alone sequel – the further misadventures of a handful of neighbors in a landmarked residential cooperative. I may revive certain characters; I might not. The possibilities are endless.

Author Links

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Leave A Comment