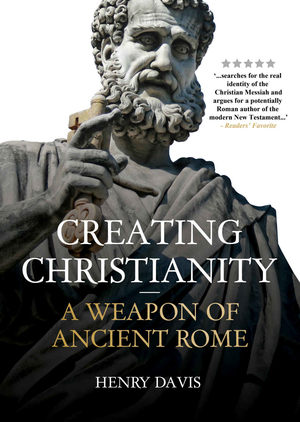

Since there is very little historical evidence of the existence of Jesus of Nazareth, many researchers, including author Henry Davis, assert that not only his person, but also the religion founded around him, were invented after his passing. Such is the case the Creating Christianity: A Weapon of Ancient Rome, a fascinating and thoroughly researched examination of this contentious topic.

Davis’s main thesis is that the gospels and other New Testament books were written not by Jewish/Christian scholars such as Matthew, Luke or Paul, but were fabricated by an aristocratic Roman family with the name Piso, notably Arrius Flavius Josephus, and that Arrius Calpurnius Piso was to all intents and purposes the first Christian pope. The tight-knit Roman families guarded the secrets of the religion’s authorship.

In support of these views, Davis notes that few people of the time could read and write, only the rich could publish, and the Caesars could simply destroy any literature they didn’t like. He points out that though the Gospels suggest Jesus had thousands of followers, no independent record of his activities has ever been revealed, nor is there any evidence of a sect of Christian groups gathering before the writings of Paul.

Of Paul, Davis notes that his name could be derived from the word “phallus” and suggests that since Christianity as created by the Romans was not catching on, sex was used as a means of drawing people in, the early “churches” being little more than brothels. Gradually Christianity grew as the Romans utilized its tenets as a powerful means of placating and controlling slaves and later, serfs, until eventually its ideals were accepted, spreading beyond Roman dominion.

Davis’s research on this subject began with encountering the writings of Roman Piso and Joseph Atwill, works that Davis freely admits have been questioned. Davis, who is briefly described as a researcher with a passion for history, presents the results of his own explorations thoughtfully, providing a plethora of supportive data. This includes lengthy listings of such arcane information as the development of family titles and pseudonyms, the translations and transpositions of numerous terms and nomenclature used in the Bible, and even a section on numerology that explains the derivation of the number 666 in the Book of Revelations. While such specificity will interest those already immersed in this unusual material, readers new to these radical ideas will be best informed by those sections that lay out, in engagingly readable narrative, the broad underpinnings of the author’s findings.

Davis rightfully stands by his exhaustive research indicating that there is no historical proof of the reality of Jesus, and that upper echelon Roman political activists were the likely authors of the New Testament as they struggled to gain control over rebellious Jews. But he also politely acknowledges that his book may well offend those with a connection to the Christian faith and its writings, so the book does not read like a scathing attack on closely held beliefs, and instead a sober investigation of the topic. He concludes that though “it is impossible to say without a doubt” that God, and even perhaps an actual individual named Jesus, does or does not exist, he advocates a belief in oneself and in making the best of the lives we are given.

A provocative and well-reasoned work, Creating Christianity is recommended for believers and non-believers alike, as the questions Davis is posing are worth exploring and well-argued.

Book Links

STAR RATING

Design

Content

Editing

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Creating Christianity: A Weapon of Ancient Rome – A Conspiracy Theory, Divine Providence, or Both?

I offer here an interpretation of “Creating Christianity: A Weapon of Ancient Rome” that neither confirms atheists’ affirmations, or religionists’ refutations, of the book, but, nevertheless, finds Henry Davis’s conspiracy theory about the origin of Christianity and a providential origin of Christianity as both plausible and not contradictory. Thus, those in both ideological camps of thought will find my review disappointing and likely triggering strong reaction (cognitive dissonance). I will borrow from agnostic historian Max Weber to explain how the supposed Roman creation of Christianity and divine providence are not necessarily antithetical.

Davis’s thesis is that the New Testament Gospels and Letters were written by the Roman senator Arrias Piso and his family clan and associates (Seneca, Pliny, Lucan, Petronius, etc.) who conspired to create a new peaceful form of Judaism to convert Jewish zealots resisting Roman occupation in Judea around the first century. Davis’s book links the Roman concoction of Christianity to the initially unsuccessful Pisonian Conspiracy to assassinate Roman Emperor Nero.

Davis employs two analyses to prove his thesis: 1) a 61-page analysis of the parallels between the Gospels and Jewish historian and Roman propagandist Josephus’s writing of his history of the Jewish War (chapter 3); and 2) a 149-page analysis of the real identity of authors of the Gospels, Paul’s Letters, Acts, Revelations, the historical accounts of Josephus and Tacitus and the first Catholic popes. Davis uses acrostic analysis (embedded code in text), numerology and genealogical methodologies to identify their real identities (chapters 4 to 10).

First, if Josephus wrote history to backstop the Christian story, Davis doesn’t explain why Jesus is not mentioned in Josephus’s writings, except for one passing reference that was apparently inserted in later versions by someone else (as pointed out by Jewish independent researcher Harold Leidner, The Fabrication of the Christ Myth).

Secondly, seemingly ridiculous on its face is Davis’s contention that his methodology proves Arrias Piso and his sons were really Josephus, Jesus, St. Clement and St. Peter, Ptolemy, Plutarch and wrote Job, Acts and Revelations. How he “proves” this is by searching the name genealogy of each person. Davis conveniently fails to consider that there were two other Roman senators with the name Arrias Calpurnicus Piso, one who served as Consul in 67 BC and another who was a general in the Numantine War from 133 to 143 BC (Wiki). Davis’s methodology suffers from confirmation bias of finding what he is searching for. But it apparently will give like-minded conspiracy theory readers what they want to hear.

It is plausible that Piso used many aliases, but Davis’s reasoning is circular. Defying statistical odds, not once does Davis fail to find what he is looking for in his investigation of family names. His analysis is more like a Dan Brown novel (The Da Vinci Code) that finds secret codes and aliases under every rock.

Nonetheless, I tentatively find Davis’s thesis plausible that those who wrote the New Testament were from the same Roman elite family clan (the Antonine Dynasty) rather than “peasants” as portrayed in the Gospels.

Despite all the faults of Davis’s book, I nevertheless find his Roman conspiracy theory to be self-evident for anyone who does a simple reading of the Christian Gospels. The Gospels call for believers to:

• Matthew: Turn the other cheek (don’t join Jewish Zealot resistance to Rome)

• Matthew: Pay one’s taxes and other tribute to Rome (Roman citizens were tax exempt)

• Mark: If one is rich, give away all their property and money to the poor (so that they cannot fund anti-Roman resistance)

• Matthew: To “go the extra mile” to help strangers (to help carry a Roman soldier’s supplies)

• Matthew: Avoid mass persuasion and hysteria which will cause those who are possessed with a demon to run to the sea and drown (allusion to Roman legions, Masada siege and mass suicide?)

• Matthew: “Put your sword into its sheath, for all who take the sword will perish by the sword” (by war against the Roman Empire)

• Luke: “Love the stranger” (Roman soldier)

• Luke: “Love your enemies” (the Romans)

• Matthew: Understand that Jesus was sent “only to the lost sheep of Israel” to convert them (the Jewish resisters against Rome)

• Mark: Not blame the Roman soldiers for the crucifixion (“Christ fiction” – but blame the Jewish priests)

• John: Lose their life for Jesus (not for the Jewish Zealots)

• Matthew: Who do you say that I am? (the son of God; contrary to Jewish law against idol worship).

• Matthew: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do” (Jesus forgives Roman soldiers but not Jews).

The above obviousness does not need Davis’s gnostic* and esoteric (understood only by a small number of people) analysis that Jesus is a humanly-created archetype for the Roman Emperor Titus (*having knowledge of the hidden secret code). Nor does it need an investigation of ancestor’s names to reveal writer’s real identities.

Assuming that Davis’s Roman conspiracy theory is flawed but plausible, to what extent can we be certain that his theory does not leave room for divine providence in the Jesus story? Is it plausible that Christianity was an unintended consequence of fraud that pullulated (spread so as to be common) to all scattered Jewish communities and the entire world?

Is it not possible that the Jesus story may have a theological origin anyway and that such unintended consequences might reflect the hand of God? This insight comes from agnostic historian Max Weber who pointed out that humans are not capable of predicting the outcomes of their actions, no matter if people otherwise believed in a conspiracy. Conspiracy theories replace the uncertainty surrounding the outcome of events. Even if Christianity was a plot to convert militant Jews, it later backfired and became the religion of the pagan Roman Empire. In other words, there may be room for providential coincidence in the Jesus story no matter if it was the outcome of fraud. If so, one might even say God had the last laugh!

To Weber, the emergence of Rome and Christianity cannot be explained by:

• The desire of one class to exploit another is not valid anymore than the end of Feudalism is explainable by the desire of the merchant and artisan classes to bankrupt the large landowners.

• Conspiracy theories are not entirely predictable because of the unintended outcomes of human action (example: Protestantism unintentionally brought about Capitalism).

• Even powerful rulers are not capable of predicting the distant outcomes of their actions.

• What we construe as the political order is the spontaneous effect of individual actions rather than their rationally constructed product.

• The social is not explained by the social but by cooperating and conflicting individuals. Thus, religion and money are not the creation of the state, elites or social class and are uniquely independent, spontaneous and not reducible (sui generis).

• Human action is paradoxical. Thus, religious or secular asceticism (avoiding self-indulgence) always creates the very wealth it denies itself. Weber stated: “puritan asceticism has always sought good and always created evil”.

• Contra Marx, religion is not merely an ideology or entirely a reflection of material interests of its social carriers and propagandist missionaries.

Thus, the collapse of the western Roman empire cannot be explained as the result of Barbarian invasions, immorality or the feminization of the culture (Edward Gibbon) but was an unintended consequence. Neither is the rise of Christianity totally explainable by Davis’s gnostic conspiracy theory, although I concur with it in part but for different reasons.

Davis’s conclusion that we can rationally learn from his study how “to avoid potentially catastrophic events” is not born out by the very history he cites. The Romans had no idea that Christianity would become the religion of its empire when they “created” it. Moreover, Christianity could not have been intentionally “weaponized” by Rome (except against Jews who rejected it) but, in fact, paradoxically ended up a weapon against Rome and its Paganism.

Disclosure: I am a heterodox Christian who does not believe that faith requires the certainty of inerrant scriptures, some propagandist posing as an historian; an infallible pope; some rare, saintly mystical experience that other people never have; some secret knowledge; some therapeutic experience; or participation in some progressive social change movement. I am equally dubious of those atheists who also seek certainty in historical relativism that would deny the human experience of religious transcendence and the mystery and awe of the unknowable. For a skeptical overview of Christianity, one might read the works of Peter L. Berger: Questions of Faith: A Skeptical Affirmation of Christianity, 2003; The Heretical Imperative (1980) and A Rumor of Angels: Modern Society and the Rediscovery of the Supernatural (1970).