FIRST lines are a book’s greeting to the reader and therefore a vital element in the whole. If it strikes the wrong note, a weak opening can nullify a great cover or an enticing jacket blurb. On the other hand, a good initial hook captures the reader from the start.

FIRST lines are a book’s greeting to the reader and therefore a vital element in the whole. If it strikes the wrong note, a weak opening can nullify a great cover or an enticing jacket blurb. On the other hand, a good initial hook captures the reader from the start.

Yet does it signal a bestseller? Consider some of these.

One of my favourite openings is from 1984 by George Orwell, and reads thus: It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.

Now here’s another teaser, simple but grabbing, from The Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison: I am an invisible man.

Any book browser has to pursue such an outrageous first-person claim.

Or how about Dodie Smith’s opening to I Capture The Castle: I write this sitting in the kitchen sink.

Why the heck is she in the kitchen sink? One can’t help but read on.

The same, yet more dramatic, applies to the intro of Run Maggie Run by John Ivor, which has been compared to a Dickens tale: A finger of sunshine poked through the grime of courtroom windows, polished the dock’s varnished panels and created a halo for the prisoner, she who was known as Maggie, age nine. The charge was murder.

A later novel, No Kiss For A Killer, allows John Ivor to flow fast action from line one: There was a time, a desperate time, when I cursed the gentle mists of my native Oxfordshire and regretted its picturesque vales and folds. Among the fruitful brown and green a deceptive dip will conceal the approach of riders.

Dickens himself is not noted for his openings, which are usually wordy and mild. His first published fiction, The Pickwick Papers, starts like this: The first ray of light which illumines the gloom, and converts into a dazzling brilliancy that obscurity in which the earlier history of the public career of the immortal Pickwick would appear to be involved, is derived from the perusal of the following entry in the Transactions of the Pickwick Club, which the editor of these papers feels the highest pleasure in laying before his readers, as a proof of the careful attention, indefatigable assiduity, and nice discrimination, with which his search among the multifarious documents confided to him has been conducted.

All one can say to that verbosity is Ouch!

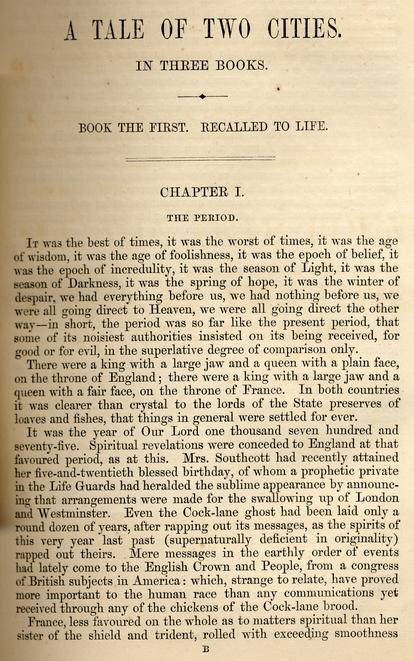

However, the opening of a later Dickens novel is often quoted: It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.

That is how he begins A Tale of Two Cities, which is a story of the French Revolution.

Another oldie, less intense than guillotine days but more intriguing in commencement, is still widely popular: Here is Edward Bear, coming downstairs now, bump, bump, bump, on the back of his head, behind Christopher Robin . . .

Guessed it? Winnie the Pooh, by A.A. Milne.

Charles Bryce uses the same technique to charm children in introducing Mousedeer: Deep in the forest comes a breeze. Hush! Hear it whisper . . .

For browsers, whether in a bookshop or online, first lines become mightily important in deciding whether to buy an unknown author. These lines need not necessarily be thrilling or puzzling. The only need is to get the reader’s interest.

Here’s one I particularly like. It introduced me to The Feng Shui Detective’s Casebook by Nury Vittachi: The tiger loping through the supermarket had blue eyes.

If that doesn’t grab you, nothing will. Now let’s glance at some current bestsellers.

Stieg Larsson, late author of The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo and other super sellers, doesn’t bother with a clever hook. He simply sweeps straight into the action, like a movie. His narrative comes close to ponderous, often boring, and yet it keeps moving.

While a good opening will influence a sale, it never guarantees a bestseller. There is no way to prejudge mass appeal. The phenomenal Stephenie Meyer began her Twilight series with an insipid girls’ school scene. No hint here of vampires and scary doings, nor worldwide fame for the author.

Dan Brown begins The Lost Symbol in gripping fashion, thus: The secret is how to die.

His thriller degenerates thereafter, yet still it has soared to bestseller status. It has the most valuable ingredient of all – a brandname author.

The 2009 Booker Prize winner Hilary Mantel opens Wolf Hall with a spoken jibe: “So now get up.” Felled, dazed, silent, he has fallen; knocked full length on the cobbles of the yard.

This is ongoing action, the middle of a fight, and encourages a read-on.

Bryce McBryce gives first lines his own delightful twist. The amusing and nostalgic Wee Charlie’s World starts thus: Smaller than a kitbag and only four years, the youngest in that army, Charlie watched the soldiers come aboard: pith helmets, khaki shorts, puttees, boots, bolt-action rifles.

The above book is presented as linked short stories while a boy grows from age four to nine pondering the weirdness of adults. All McBryce chapter opening are good, but one demanding instant attention kicks off The Spirit of Waterloo: Alphonse haunted the garrison school because it was there. It was heavily there, on his grave.

Brilliant lead-ins will always have their place in literature but do they really matter to the eventual destiny of a book? This is a question I challenge readers to answer, because there is no analysis that can enlighten us for sure. Apart from brandname authors who sell millions on reputation alone, it remains a mystery how book readers will respond to a particular title.

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

I think the modern reader has to–or chooses to–wade through so much hype before reaching the opening line, that even a good opener feels like an afterthought, perhaps only a bolster to the buying decision.

If you encounter the book in a store, you touch it, weigh it, read the flaps and back cover, perhaps read more hype inside. And then you get to Line 1, possibly following a pithy chapter title.

If you buy online, you get all the hype and might read the top three customer reviews before you make your buying decision, which you typically make without touching or leafing through the book.

Line 1 now seems anticlimactic.

I buy online only when I already know what I’m getting. In a bookstore, I pay very little attention to ‘packaging’. I open and read.

I tend to open and read too. I usually skim through the first page to see if I’m interested in buying the book. I really believe in the importance of the first line. It has to have some element of mystery that makes me want to continue reading.

I did a post a little while ago about this first-line business. I completely agree with you that it’s a mixed bag – another variation that I look at is the oft-overlooked second sentence, where a lot of good books have their hooks.

Really, though, I think it’s just a matter of hooking readers at some point in that first half of the top page. It might be writing, or a teaser, or just what’s actually happening in the story. Being too literal and saying “you have to hook them in the first sentence” seems to yield more disastrous attempts at wit than actually good hooks.

Interestingly, I’d consider that line about the tiger with blue eyes to be one of those overdone, too-obvious attempts to hook. I think my being an editor makes me harsher on this kind of thing than the average reader, though. I see that and think “yeah, the author’s trying to manipulate me” and put the book right down again. Just goes to show, eh?

Anyway, here’s the link to my post, for your further-pondering-the-issue pleasure:

http://blog.kallisti.ca/2010/04/its-second-sentence-stupid.html