Much of the time, self-publishing has a lot in common with the traditional small press. So it’s important for self-publishers to look at the successes and failures of indie presses to learn about how to survive in this climate. And it’s rough out there. Last week, Quarter Press, an up-and-coming romance e-publisher announced – very abruptly – that it was closing up shop. There aren’t full details of why this went down, but the info that’s available is pretty instructive about what it takes to start your own publishing house.

Kassia Krozser of Booksquare and partner in Quartet wrote about the difficulties of navigating the incredibly complex world of e-publishing. She writes,

The first thing you need to know is that there are very few industry best practices. They are developing rapidly. Don’t expect today’s rules to apply to tomorrow’s business, so plan for change, failure, and unexpected success (with a little expected success to make you feel good). I would not, however, suggest, for anyone starting in the digital first or digital only realm, to look to traditional publishers for guidance. Okay, maybe a few, but only in the instances where those publishers are doing it differently and taking real chances. Anyone who isn’t engaged in a level of messy experimentation, they’re not worth using as a role model…

Here are some pain points to consider as you try to build a digital publishing business — this is an incomplete list, of course: ISBN madness (really, one ISBN for every format? the mind continues to boggle) and alternate product identifiers; formats, formats everywhere and not a hint of resolution; third party distributors, or, how do you get your books to retailers in the most efficient manner?; customer service (see: formats, devices, and all-around confusion); the challenges of getting your book to show up in retail outlets before release, particularly when you don’t have a corresponding print product; the imposition of DRM despite your stated preferences (really, who are the retailers protecting when they force DRM on the publisher?); pricing and consumer savvy….

What we learned was that any financial model one builds for the ebook world must throw away traditional assumptions. Yeah, if you build everything around the belief that that those crazy customers will embrace your internal $26.99 price point model, then, yes, when Amazon and others start demanding better terms — and they will, they will — it’s going to kill some of your business. So it’s easier to start from the bottom, figure out what it’s going to cost, and then build the model.

Really, read the whole thing because it has direct applications to self-publishing. There are far more self-publishers than there are those who start an independent press – and in this climate it’s incredibly hard to keep any literary venture afloat.

Angela James, who was just hired on as editor, wrote:

To say I’m sick, and sad, and shocked (and other “s” words you can think of that might be appropriate) and, yep, angry might be putting it a little mildly. Who would have expected this? But as with my joining of Quartet Press, it’s abrupt closure has caused a lot of speculation, some general nastiness and lots of disappointment, and I know people are looking for some sort of answers that I’m very sorry I can’t give publicly. At the same time, the offers of support and well-wishes have been more overwhelming than anything. Thank you.

Publishing is a business, and like any other business, the chances we take and the choices we make aren’t always going to work out how we planned.

So what’s this all mean for self-publishers? It means, for one thing, that the state of publishing is in flux – the rules are changing and no one quite has a handle on how to manage the ebook revolution. It also means that a self-publisher might have it easier than a full-bore press that needs to turn a profit in order to pay its writers and cover overhead. There’s one truth to self-publishing: you’re probably going to lose money, at least at first. Count on it. But because you’re not carrying the weight of other writers, you will not drown in debt as quickly.

Because of this, a self-publisher has more freedom to undersell the prices of traditional presses. Sure, a self-publisher wants to turn a profit, but this shouldn’t be your sole motivation – it should be to find readers. Given the decreased distribution that comes with self-publishing, charging less for an ebook is a good move because it increases the potential for sales. We’re at the point right now where ebook readers are far less cynical about self vs. traditional publishing: they just want books to read, and if they’re cheaper, good. So self-publishers have a real advantage in being competitive in the ebook market.

The same does not hold for print, and this is where self-publishers really lose out. It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense for self-published writers to charge $20 per book. More expensive + less well-known is not a good combination. So as much freedom as Lulu provides, it makes a lot more sense to truly be a self-publisher and go directly to Lightning Source. Really, all Lulu is doing is providing a layout service, for which they charge a hefty fee per book – as is the case with all LSI-affiliated subsidy publishers. Instead, establish a real print outlet and publish directly with LSI. From a purely profit standpoint, it makes sense.

But Quartet wasn’t even testing the print waters – they were e-only and the enterprise eventually dissolved. The lesson for self-publishers is pretty basic: it can be as hard for indie presses as it is for self-publishers, which is in part why self-publishing is gaining clout. Right now, it’s hard for everyone to navigate the waters of the publishing industry, so it’s harder to thumb your nose at self-publishers when everyone’s in the same boat.

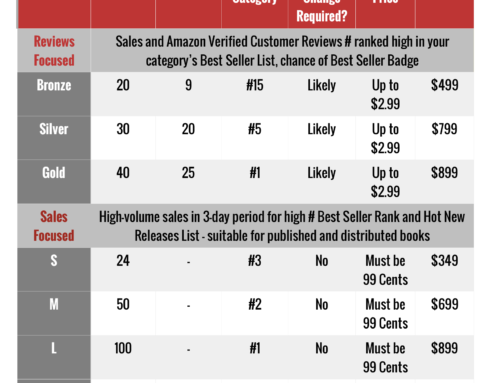

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Henry,

A sobering and informative piece on Quartet. Certainly the ground is shifting almost daily in publishing, epublishing and distribution. I think the turmoil also helps to point out what serious self-publishers (or independent publishers) have known for a long time. The right author, with a book produced at a professional level and editorially indistinguishable from other high-quality books in the market, regardless of who published them, still is an excellent and conservative business model for making money (eventually) at niche nonfiction.

But that is very far away from many of the ebook pushers and the “self-publishing factories” that are turning out the 1000 books a day we hear about so often.

Well, if I had to pick which boat to climb into, and I do, then I’ll take Random House, thank you very much. Some things in business never change no matter how much or how many would be authors want them to. Quality rules!

I just want to say, the people at Bowker are smoking crack if they think I’m using ISBN’s for my ebook formats. Ebooks are digital sales. they are automatically trackable. Sounds to me like a good plan to sell more ISBN numbers to people who want to look serious while losing their shirts.

Zoe,

The people at Bowker can afford all the crack they want. How do you like their business model? They sell numbers. No inventory problems, no cost of production, no royalties. Just numbers.

LOL Joel, actually it’s brilliant. I wish I’d thought of it.