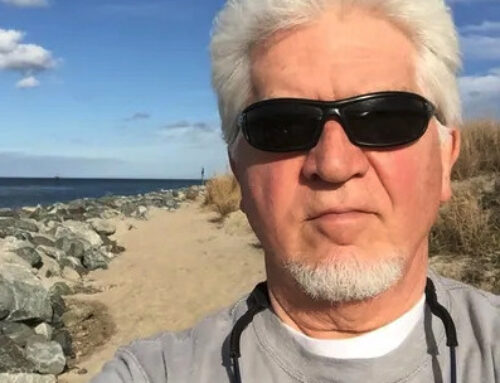

Bob Ashley is a herpetologist, serial entrepreneur, and museum director. He has a lifelong passion for reptiles and amphibians, beginning with a childhood fascination with the local turtles and snakes in his home state of Michigan. He’s turned that passion into a multifaceted career with a theme of advocacy and education. Bob founded ECO Wear and Publishing nearly thirty years ago, a company that offers natural-world-themed apparel, art, and books. He’s published more than 40 books on reptiles and amphibian natural history.

Bob Ashley is a herpetologist, serial entrepreneur, and museum director. He has a lifelong passion for reptiles and amphibians, beginning with a childhood fascination with the local turtles and snakes in his home state of Michigan. He’s turned that passion into a multifaceted career with a theme of advocacy and education. Bob founded ECO Wear and Publishing nearly thirty years ago, a company that offers natural-world-themed apparel, art, and books. He’s published more than 40 books on reptiles and amphibian natural history.

Bob is also co-founder of the North American Reptile Breeders Conference and Trade Shows with partner Brian Potter and a former president and current Vice President of the International Herpetological Symposium. In 2009, he opened the Chiricahua Desert Museum in New Mexico as an educational exhibit of reptiles and amphibians associated with the Western Hemisphere and the deserts of the Southwestern United States and Mexico. He has served continuously as its director since its inception.

His wife, Sheri Ashley, works with him at the Chiricahua Desert Museum, managing gift shop buying, marketing, and order fulfillment. Their miniature schnauzer, Trixie, also works at the museum as the official guest greeter.

Tell us about your book.

I started collecting snake bite kits about 10 years ago. Initially, I was buying kits for a good friend of mine in Australia, who had been collecting them for 50 years. Whenever I visited him once a year, I would bring a few extra kits from different places. As I collected these kits, I developed an interest in them myself and began my own collection. Over time, I ended up buying several collections and received many items from my friend when he retired. Now, at the (Chiricahua Desert) museum, we have a display of almost 200 kits, more than we had when I wrote the book. Our Science Director, Gordon Chewett, suggested we do a book on this eclectic and interesting collection.

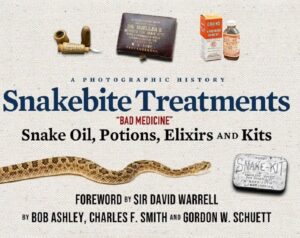

Two years later, we published a book that includes various anti-venoms, snake oils, snake bite kits, tourniquets, and other related items. Interestingly, most of the items don’t work at all, except for the snake anti-venoms. That’s how the collection started and eventually led to the book. Through a rich series of photographs and text, A Photographic History of Snakebite Treatments, Bad Medicine: Snake Oil, Potions, Elixirs and Kits, chronicles the history of snakebite treatments, from the approach we call “kill ‘em or cure ‘em” to the era of modern medicine involving anti-venom.

Why did you want to write a book?

Why did you want to write a book?

I’ve always been interested in history, and a lot of it is at risk of being lost forever – like the old snake oil salesmen and the old carnivals. I’ve always found those fascinating, so I started collecting related items. I think there’s a population out there that would find it interesting. If we don’t save and preserve these things, they’ll just disappear, becoming part of the folklore and history of our existence that would be lost.

What was your steepest learning curve during the publishing process?

It’s all about marketing and promoting. You need to find a way to market your book effectively. We specialize in a very niche market, so it’s tough. If you pay to market to the general public, only a tiny fraction might be interested in your book. You can’t afford that because you’ll never recoup your advertising costs. Social media and other modern tools are essential for this. These tools didn’t exist 10 or 15 years ago the way they do now. Today, you can write a book on snakebites and market it through Facebook forums, podcasts, and similar platforms to reach your target audience.

As a writer, what is your schedule? How do you get the job done?

I worked on some of this towards the end of COVID, doing little projects here and there. Often, I would come to the museum around 4 or 5 o’clock in the morning to work on things when the phone wasn’t ringing and things weren’t crazy. I’d put in an hour or so before the day started, then set it aside when the regular workday began. Gordon Schuett, our science instructor, is a PhD and one of the best editors I’ve ever known. Without him, my handwritten notes and drafts wouldn’t have been edited properly. He played a major role in making this book what it is today.

How do you deal with writer’s block?

When I write, it usually takes me about half an hour to 45 minutes to organize my thoughts, almost like creating an outline. Once it starts to flow, I get interested—especially when I discover a fascinating new tidbit of information during my research. It takes me that initial half hour to 45 minutes to get into the groove. After that, I can sometimes write for 4 or 5 hours straight. It’s hard to accomplish much in just half an hour because I need that time to find my way. Once I do, I grab onto an idea and follow it, like a trail of popcorn through the woods, maintaining a steady train of thought.

Why did you write about this particular subject?

I love the history of it all. Part of the excitement is in the chase. I have a couple of hundred old snakebite kits, and sometimes I come across something truly unique. Recently, I found an antique snakebite kit on eBay by searching under “antidotes,” which I hadn’t tried before. Some of these items can sell for $200 to $300, but this particular kit, which included old glass-blown suction cups with a rubber part from the late 1800s, was listed incorrectly and I got it for just $8.17. If it had been listed under “snakebite kits,” it could have gone for $700.

The thrill is in finding these rare items. Usually, there are many listings of common items I already have, so it’s rare to find something new and exciting. There’s also the competition – there are a few other collectors like me, and we often drive the prices up for each other. Sometimes, I’ll end up paying $600 for something I really wanted. It’s a fun and exhilarating hobby, despite the occasional high price.

Why is it important for a layperson who may not know that much about snake bites to go deep into that niche and read your book?

If you’re interested in history, it’s amazing to think about how people used to handle snake bites. You can still go to a sportsman store or a hardware store and buy a snake bite kit today, but they don’t do anything at all. A band-aid would be better because it won’t cause any harm. Knowing how to properly take care of yourself if you get bitten by a snake is very important. If you get bitten by a snake and you’re not sure if it’s venomous, you need to go to the hospital for treatment. Our bodies react differently to snake venom, much like how some people can have severe reactions to bee stings while others do not. One person could get bitten by a Western diamondback and have mild effects, while another might have a severe reaction. So, knowing what to do in case of a snake bite is crucial for everyone.

What did you learn by writing this book?

I learned a lot while researching these kits. My friend, a photographer, helped by illustrating the entire thing. He photographed the kits against black velvet to showcase all the different, eclectic parts, like strychnine and other components they included for treatment. I also researched ancient texts like the Brooklyn Papyrus from ancient Egypt to learn how they treated snake bites. Through this process, I gained twice the knowledge on the subject compared to what I knew before I started. I learned a lot about the dates, companies, and how these kits evolved.

What was the most surprising thing you learned while writing this book?

There weren’t many surprises, but I did come across some fascinating anecdotes. For example, my good friend John, from Australia, shared a story about historical snake handlers and snake oil salesmen. These men would let venomous snakes bite them repeatedly to build up immunity. However, this practice could also lead to hypersensitivity, making subsequent bites potentially fatal. One such snake oil salesman convinced people to buy his antidote by letting snakes bite him. Unfortunately, one mayor, skeptical of the snake’s venomous nature, insisted on being bitten and died because he wasn’t immune, unlike the charlatan.

This story highlights the dangers and misconceptions surrounding snake bite treatments. There’s no oral treatment for snake bites that works, but there’s a promising new treatment undergoing FDA trials. This oral medication could suppress the effects of neurotoxic snake bites, like those from cobras in India, until the victim can reach a hospital. If approved, it could save tens of thousands of lives.

What are your plans now your book is published?

We’re marketing it through various channels, including podcasts and extensive use of social media. I also give talks; for example, I was flown to Prague this winter to speak about snakebite kits and treatments. I’m scheduled to give another talk in Knoxville, Tennessee, at the International Herpetological Symposium in June.

Author Links

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Leave A Comment