Jeff Lee, a retired educator and once avid sailor, currently divides his time between Chester County, Pennsylvania and Lewes on the Delaware Bay, where he now directs his creative energies to his life-long love of writing.

Jeff Lee, a retired educator and once avid sailor, currently divides his time between Chester County, Pennsylvania and Lewes on the Delaware Bay, where he now directs his creative energies to his life-long love of writing.

Tell us about your book.

Set in 1955 in Lewes on the Delaware Bay, the novel Karl Myers meets James Ellroy’s characterization of Noir as “the wrong man and the wrong woman in perfect misalliance … it canonizes the inherent human urge toward self-destruction.”

Former Marine and small-town police chief Karl Myers is one of four principal characters, each of whom hurtles headlong toward personal demolition; the others are Jerry and Vivian Peterman and their 12-year-old son, Greg.

Myers’ marriage had dissolved before WW II, and the life that has followed has been a life lived in the strange world of uniforms where a man, surrounded by hundreds of other souls, can find himself sucked into an unyielding vortex of loneliness, which threatens to drown his soul. Jerry’s abuse of Greg and Vivian, and Vivian’s rationalizations for accepting it, have created a dysfunctional family that is on the brink of collapse when there is a horrific accident.

Greg, along with the reader, knows what has happened, and the boy is fearful of his father’s certain retribution, but the boy successfully hides the truth from his family and from Myers until the chief resolves the mystery almost too late to save the victim’s sister, who is in a catatonic state caused by the trauma of witnessing the accident. Complicating Myers’ challenges are the attitudes of too many White residents in Sussex County toward their Black neighbors–like Moses’ African-American mother–attitudes that reflect the enduring White supremacist beliefs of the Confederacy; for example, schools and many public places in Sussex County, including hotel accommodations, are still segregated in 1955.

Another war has a bearing on the people of Lewes and the nation in 1955: the crucible of World War II produced a generation of heroes who understood manhood as a stoic duty that demanded complete intolerance of weakness. Many returned from battle eager to raise sons who would be prepared to bear the responsibilities of a hard world. Military service had forged warrior personas by replacing personal will with unquestioned obedience, the denial of which threatened pain and humiliation or worse.

Many veterans returned from the war believing their sons would benefit from the same demanding discipline that they had followed on the battlefields of Europe and the Pacific; unfortunately, unyielding expectations communicated through clenched teeth or china-rattling shouts, often reinforced with untempered smacks from calloused hands, or worse, a father’s disdain applied to the soft underbelly of a child’s ego, spawned a cadre of boys in the 1950s who craved the approval of their fathers while being simultaneously terrified of them.

Why did you want to write a book?

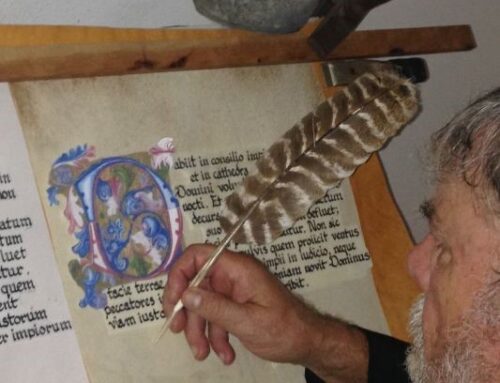

The wanting to write was unwittingly born in 1956, when at the age of 9, I discovered novels, the first of which were Stevenson’s Treasure Island, DeFoe’s Robinson Crusoe, and an abridged version of Sir Thomas Mallory’s King Arthur, the copies of which I read having once belonged to my father when he was a boy. At 11, during my first exploration of a high school library left behind at a newly configured junior high school, I encountered Joseph Conrad’s The Shadow Line, which cemented my lifelong devotion to the novel: the longer and more intricate the plot, and the more elegant the writing, the better!

Why did you choose to self-publish?

Why did you choose to self-publish?

25 years ago, I needed to make a choice: use my time, energy, and intellect to pursue a very uncertain career as a writer, or pursue my then career as an educator, which promised a much more likely return on an investment of time, energy, and intellect. I choose the latter, but I could not stop writing, so I continued to write for the sheer joy of it.

Influencing that choice was what I had learned about publishing: finding a literary rep that would be essential to being published by a traditional publishing house did not involve the quality of one’s writing as much as 1) going to a college noted for its writing program would have been, a school where one can ingratiate oneself with professors who would be willing to push your work with friends in the business, and 2) having the financial means and time to network via writers’ conferences et al.

With the advent of services like Xlibris, and then CreateSpace, the opportunity to publish a book that I could hold in my hands was too much to resist. I have written and self-published a handful of novels and until now, I have made no significant attempts to market my work.

What tools or companies did you use, and what experience did you have?

I published my first book Angel In the Valley via Xlibris, but all my other titles have been published by Amazon services: CreateSpace and now KDP. In every case, I have found the related technology easy and interesting to use. I use Word to write and format the content, and have used MS Paint to craft covers, but since I have recently decided to spend some energy and money on marketing, I am using rockingbookcovers.com as a relatively inexpensive resource for great-looking covers, and I am considering working with amazonkindlenetwork.com to design the cover for a revised and polished edition of The Helper.

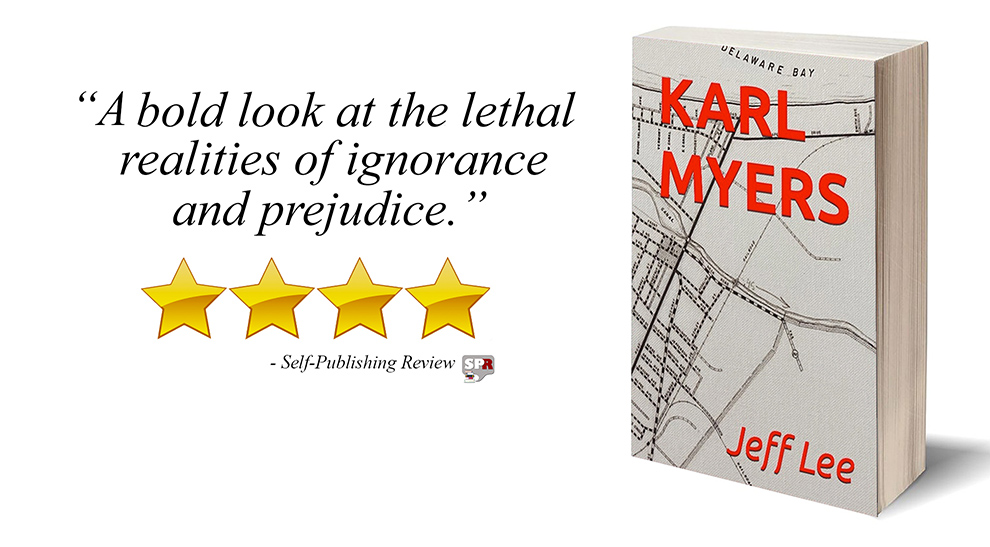

Paying for a third party like Self-Publishing Review to review your work can be a tad expensive, but it can also be one of the more helpful things a writer interested in marketing a book can do. Those reviews are a hell of a lot more valuable than the friends who read your book but are loathe to be truthful because they love you.

What do you think are the main pitfalls for indie writers?

There are two. The first pitfall is delusion, manifest in the apparent belief of especially first-time novelists that there is a Publishing Fairy who will whisk one’s manuscript straight from one’s computer to a Big-Four publishing contract. I was fortunate to receive this advice at the very beginning of my writing “career” from Peter Bart (a movie executive, novelist, and editor of Variety who was married to my then wife’s BFF): “Never write a novel because you want to make money, because the chance of that ever happening is slim and none. Write because you like to do it.”

Time and again over the past 25 years, I’ve spoken with wannabe authors who have just begun to write what they are certain is going to be the next great American novel. In “Writing Books Is Not Really a Good Idea,” Elle Griffin writes: “People don’t read books – and the ones that do aren’t buying them. To make matters worse, ‘books that publishers released’ are only the ‘success stories’ – those books that scored hard-won Big-Four publishing contracts – and those are already a small piece of the book publishing market.” According to Bookstat, which looks at the book publishing market as a whole, “there were 2.6 million books (titles) sold online in 2020 and only 268 of them sold more than 100,000 copies – that’s only 0.01 percent of books. By far, the more likely thing is to sell between 0 and 1,000 copies – and that was 96 percent of books last year.”

The second pitfall is the handmaiden of delusion: workshops and other costly learning opportunities offered by failed authors, a burgeoning American industry that exploits the delusions of wannabe novelists whose naiveté makes them impervious to the obvious: the insignificance of the commercial success of the literary works of the purveyors of said industry may be evidence of the actual value of said purveyors’ advice.

What tips can you give other authors looking to self-publish?

Read, read, read as much as one can of as many varied authors as possible, not to imitate what you read but to allow what you read to permeate into your writer’s mind. And then write, write, write, and rewrite until what you’re reading satisfies the innate need to create that resides within you. You can access lots of information about marketing just by browsing the internet, reading articles about success stories and strategies et al, but beware delusion! When you have a finished novel, consider paying for a review and then consider incorporating any suggestions therein to improve your work.

As a writer, what is your schedule? How do you get the job done?

When I was working, I would just make the time to write, which is a hell of a lot harder to do than to say. Discipline is essential, and so is something that I have heard/read over and over again in interviews with “successful” writers: “I just have to write; I cannot not write!” Without that intrinsic emotional need, discipline is even more difficult.

How do you deal with writer’s block?

God, I hate this question because I’m afraid my answer will “jinx” me! I cannot recall ever having had writer’s block. Perhaps the reason is because I become obsessed with escaping into my characters’ lives and into their stories, and my favorite thing is waking up in the morning and finding fully formed in my mind, a plot direction that resolves an obstacle I recognized the day before. Obsession with writing, having the emotional need to write and create is, I suppose, a unique blessing for which I am most grateful.

Tell us about the genre you wrote in, and why you chose to write this sort of book.

I write historical noir mysteries and adventures about fictional characters that lived in the last half of the last century. I did not choose this because I thought it would be commercially advantageous (beware delusions!); rather, the genre ended up choosing me because doing so gave me pleasure.

Who are your biggest writing inspirations and why?

Conrad, Maugham, and Dickens have provided the most influence on my writing because I honor their mastery of the English Language and I admire their capacity to create complex and believable characters and stories.

Author Links

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Leave A Comment