You’ve had the line edit and worked on the notes your editor gave you. You’ve had the manuscript proofread. Then why is the biggest issue with self-published books is that they get published too early in the process? Editor Cate Baum gives you ten reasons why your book may not be as ready as you think it is.

You’ve had the line edit and worked on the notes your editor gave you. You’ve had the manuscript proofread. Then why is the biggest issue with self-published books is that they get published too early in the process? Editor Cate Baum gives you ten reasons why your book may not be as ready as you think it is.

Lately, I have been editing books for authors who have already paid for edits, some with reputable editors. I have seen a sharp rise in remedial edit work coming my way. The issue is that their edits just were not aggressive enough, and the author’s reviews end up commenting on bad structure, plot holes, and weak characters. As an editor, it’s scary to walk the line between upsetting your author with too many notes, and not enough, but simply put, a good edit will follow certain guidelines to ensure an author will end up with a solid book to sell. Here are ten reasons I see most often that mean a book should not have been published in its current form.

1. You haven’t done enough work

A successful book may need seven or eight rounds of editing to nail the essence of the story. When I line edit a book for the first time, I round down on issues that are the biggest problems in the story, but most often I advise the author to come back for a further edit once they have worked on those issues. This is not because I need the work (I’m inundated!) but because a trade book, for example, will be edited up to ten or eleven times by various editors, the agent, and the publisher before it makes it to the publication stage.

Why? Because despite everything, there are notes that need to be hit in a reader’s world that have to be present in each book, whether it be fiction or non-fiction, to communicate your writing successfully. Don’t rush your editing phase. Make sure the book is entirely ready before you hit the publish button.

2. Dialogue as exposition

Dialogue is often a massive issue in stories that have a lot of backstory. Dialogue should not be the way that you tell your readers about an event. Show don’t tell. Dialogue that has more than one or two exchanges is running into exposition. One of the biggest turn-offs for agents and readers alike is pages of dialogue filling them in, as if they are simply eavesdropping instead of living in the moment.

You can do the scroll test to check how you are doing. Scroll through your Word document and if you see a lot of narrow text in a column, you’ve got far too much dialogue. How much of this can be action scenes in the present? Rewrite, experiment.

3. Overuse of Adverbials

Often, authors starting out will overuse something called adverbials to a ridiculous degree. This comes from inexperience in writing description. This is known as too much TRaMPing. Time, Reason, and Manner, Place.

In the summer (Time), despite knowing he’d be there (Reason), she’d nervously (Manner) go to the beach (Place).

Which is fine once. But when you start using the Manner part of this sentence over and over again, the “-ly” words add up. When you start putting the Time and Reason into every sentence, that’s when your writing starts to fragment.

4. Adverbs are evil

And so to the bad habit of adverbs in book writing. Adverbs belong in learning language, not in prose. If a character tells another to shut their mouth, we don’t need to know they said this “angrily,” because we can infer they were angry by what they said. The prettily made pink skirt is pretty by default. Adverbs are like weeds that spoil the flow of sentences, and need to be used with great caution. I’ve seen arguments that this advice is going out of fashion, but it’s just not true. Good writing doesn’t need the cheap trick of adverbs.

For more on why adverbs ruin your prose, don’t take it from me. Stephen King hates them the most.

“I believe the road to hell is paved with adverbs, and I will shout it from the rooftops. To put it another way, they’re like dandelions. If you have one on your lawn, it looks pretty and unique. If you fail to root it out, however, you find five the next day… fifty the day after that… and then, my brothers and sisters, your lawn is totally, completely, and profligately covered with dandelions. By then you see them for the weeds they really are, but by then it’s—GASP!!—too late.” ― Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft

UNLESS…

The adverb is your friend when you use it to mark out an opposite condition to what would be expected. For example, the pink skirt may be terribly made, by a monster for his captive princess. Maybe a dentist is kindly telling a child to shut their mouth after being brave with a tooth.

5. Characters are flat/tropey/offensive

Characters are easy to get wrong, because authors write characters they don’t know. Not knowing how a fifteen-year-old reacts to bad news, or how a woman’s thought process is different to a man’s about fixing a car, for example, will make your story falter. Often I see characters who blend into each other, and have no real voice. They speak the same, have the same opinions, and react the same. The reason for this is that the author is simply using them as an avatar for themselves instead of observing others, and crafting a personality for each character.

This issue often leads to characters that “have it all.” I’ve seen authors describe their characters as literally “having it all” in their blurbs! Beautiful model Savannah is also a pilot and works for the Peace Corps. She is also a millionaire. Come on!

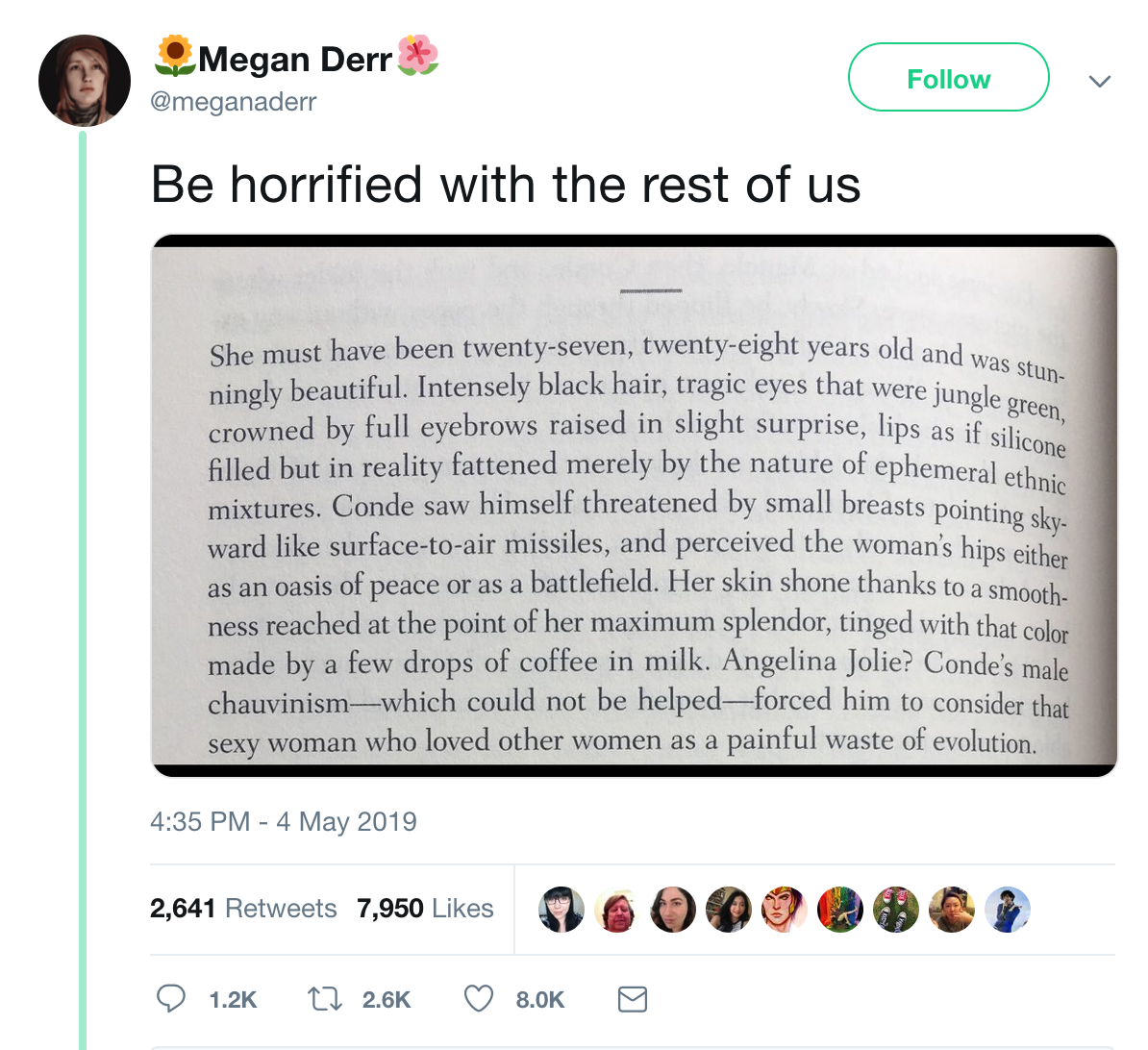

The sets of smouldering “jungle green eyes” (ugh) and legs up to their shoulders I’ve read, you’d think all men are married to supermodels, and all men are also supermodels. Careful also of describing BAME characters and trans characters. This particularly unthinking “jungle green eyes” piece discovered by author Megan Derr was met with horror by feminists and anyone of color recently on Twitter, shared almost three thousand times:

It’s actually more likely readers will loved flawed characters of average or ugly looks, or those with bad or peculiar personality traits. Take Scrooge, Malvolio, Villanelle, Lisbeth Salander, Patrick Melrose, Jay Gatsby. How much more interesting would it be for your character to find a woman attractive who is not gorgeous, because of a certain trait? Jane Eyre, for example, is described as ugly, but the dashing Rochester falls in love with her anyway.

6. Characters as lazy vehicles

Characters sometimes only exist to have thoughts about the plot, and those thoughts come in flashback or opinion so that the reader can learn backstory. In fact, that character is useless, and should not exist, because they do not advance the story in any real way. Ask yourself why you cannot just have these facts of the story in front in real time. If it is backstory, does the reader really need it? Write the scenes as action, not dumping facts as thoughts on the page.

7. Characters’ thoughts

Talking of characters’ thoughts…using a character’s thoughts in italics at all is so hackneyed at this point that it’s a real turn-off for readers. This is a book, not a radio play!

Tansy swiped at the monster. If only I could cut off his head!

It’s not necessary to know what she’s thinking at all. Put it into action.

Tansy swiped at the monster‘s head.

8. Punctuation

Lazy punctuation used on phones, as well as emoticons, seems to have got into our prose. Here are some punctuation marks that are not acceptable.

- Ellipses written as more than three dots. An ellipsis is three dots (…) and no more. So, ….. is not an ellipsis, but a bunch of dots that means nothing. An ellipsis should only be used when dialogue is trailing off, not interrupted. For interruptions in dialogue, use an em-dash.

- The ?! or the !? is NOT an acceptable punctuation mark. Choose one. If it’s a question, use the question mark, if it’s an exclamation, choose the exclamation mark.

- :), i.e. the smiley face, does not belong in prose unless you are quoting a text message.

- Start a new paragraph, i.e. a new line ONLY if a.) someone new starts talking, or b.) a new scene or idea starts. Otherwise, remain in the same paragraph.

9. Overuse of names

If there is only one woman in a scene, there is no need to use her name after the first time. You should then go to “she.” The only reason you would keep using her name, is because there is another woman in the scene. You can also link actions from the same character with an “and.” For example,

Sheena walked over to Steve and Mike and dropped the file on the desk. Sheena smiled. “What’s up?” Sheena sat down.

becomes,

Sheena walked over to Steve and Mike and dropped the file on the desk and smiled. “What’s up?” She sat down.

10. Lack of Plot Transparency

When you started this book, you had a convoluted plan for its plot. How do I know? Because everyone does. Sometimes I have taken out whole threads, in fact, whole chapters, where an author thought they would weave various characters’ stories into one book, kind of like the movie Crash, or the TV show LOST. The problem with this is that often those threads actually stop us from getting to know one set of characters in one story, unless the additional stories actually come together, like in Crash or LOST, in a clever way.

Expecting your reader to remember that so-and-so used a pen on page 13, and on page 215 another character used the same pen, for example, is too much to ask. Don’t be mysterious. There is a sparse amount of reveal needed in a book, because the reader will see through attempts you make to conceal ideas. You will then, in much the same way we might desperately cover a zit, start piling on stuff to cover up the evidence. You may even write new characters in an attempt to throw your reader off the trail. And you will end up losing your reader, confused and worn out, who gives up on what could have been a solid, strong story if only you’d got rid of all the extra bits.

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Leave A Comment