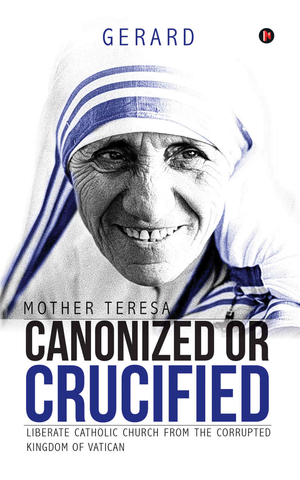

A Catholic Christian writer asserts that the Vatican sought to prevent the canonization of Mother Teresa, the Albanian-born nun who created a community convent in the slums of Calcutta, in Mother Teresa Canonized or Crucified: Liberate Catholic Church from the Corrupted Kingdom of Vatican.

Author Gerard presents his case against the Catholic hierarchy with a combination of cold logic and heated diatribe. He believes the loving service of Mother Teresa should serve as an example for all Christians and that the Church should open the roles of priestess and bishopess, cardinal and even Pope, to women, giving Catholic men more time to do the kinds of social outreach that Mother Teresa was noted for.

Gerard explains the process of beatification and canonization, which, by Church law, can only happen after the death of the proposed saint, prompted by two miracles that must occur through the spiritual presence of the candidate. In the case of Mother Teresa, he sees the approval process as having been needlessly prolonged and at times, stymied.

Rather like a modern Martin Luther, the author rails against the Catholic structure in which priests are called “father” and are the intercessors, along with saints and the Pope, between humans and God. He extols the virtues of Mother Teresa, who treated the sick and ministered to the dying without requiring any form of conversion from their traditional religions. He sees her as a bold exemplar of the idea that anyone can access God directly, and accuses the Church of wishing to maintain power by enforcing religious conversion on those they help physically. Initially, Gerard notes, Mother Teresa began doing the work in India on her own, and only later garnered support from the church. She began her mission 17 years before the Vatican II Council decreed that the Church could engage in such “merciful acts for the people and the poor.”

Gerard, about whom little information is supplied, has clearly researched the situation of the Vatican’s treatment of Mother Teresa’s possible sainthood in deep detail. He notes that the Church officials released her confessions, which contained her stated wish that they be destroyed. He decries Church custom that allows statuary to be clothed in silk and jewels when someone like Teresa wore only simple saris woven by the poor folk of her community. As his argument builds, it becomes plain that his real opinion is that Mother Teresa should not be canonized at all, believing that her sainthood would “ring the death knell for her charitable service of 49 years.”

Curiously, this book was published less than a month before Mother Teresa was officially canonized, a circumstance the author almost certainly knew was in the offing. Unfortunately, his readers are not privy to his reaction to that significant event. While that fact does lessen the impact of the book’s central argument, the book does cover other important topics beyond the canonization of Mother Teresa, such as that women be given more power in the Church and ordinary people be allowed to feel that they have a direct connection to the Almighty.

Though the book is not necessarily well-timed for some of its focus, and suffers from editing issues as can be seen in the book’s subtitle, thoughtful Catholics and other religious activists may find in Gerard’s points a helpful guide to future useful changes in the internal structure of the Catholic Church.

Book Links

STAR RATING

Design

Content

Editing

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Leave A Comment