What are we talking about when we discuss the “voice” of the character you have created in your book? We’re discussing the way in which your character communicates with others in dialogue, but also how the character thinks and narrates to your reader. This is more than just how your character talks. This is the whole inner world of your character.

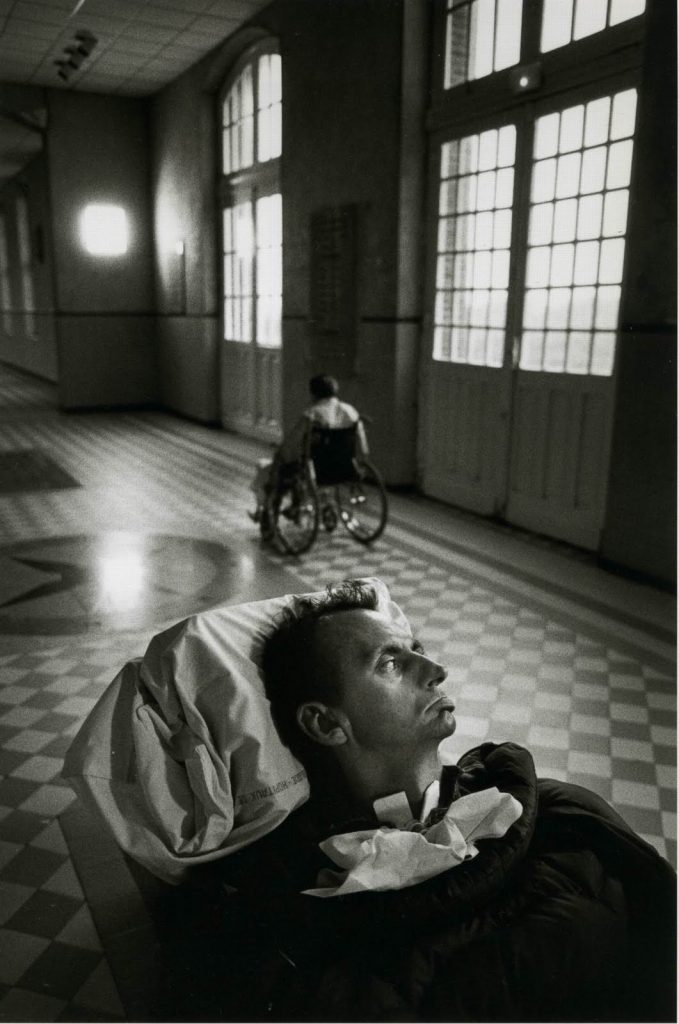

Jean-Dominique Bauby was paralyzed when he wrote his memoir

1. Physical Aspects

Your character needs to be able to communicate from within the body you gave them. A deformed mouth may mean no talking out loud, but the character can think and communicate to the reader. If your character is poorly, or a drunk, these aspects of their demeanor need to reflect in the energy they give to communication also. Look at how this passage from the memoir The Diving Bell and The Butterfly describes how it feels to be completely paralyzed when the protagonist is an incredibly intelligent and refined man (the author Jean-Dominique Bauby was previously the editor of Elle magazine in Paris before having a stroke that gave him Locked In Syndrome).

Speech therapy is an art that deserves to be more widely known. You cannot imagine the acrobatics your tongue mechanically performs in order to produce all the sounds of a language. Just now I am struggling with the letter l, a pitiful admission for an editor in chief who cannot even pronounce the name of his own magazine! On good days, between coughing fits, I muster enough energy and wind to be able to puff out one or two phonemes. On my birthday, Sandrine managed to get me to pronounce the whole alphabet more or less intelligibly. I could not have had a better present.

2. Vocabulary

The best way to set out your character’s voice is to plan their vocabulary. You don’t want your own author’s foibles invading the novel, so if you always say “OK” or “cool beans”(let’s hope not) or “wonderful”, ensure you map out which characters will say what words as a habit. We all do it, but it needs to be distinct in each character, and should only cross into another if the characters are, say, married a long while, or brother and sister. Remember people have “in-jokes” and words that can mean anything to the people in that relationship. You can also add local words if say, your book is set in a small local community. Mapping the language of each character will help prevent your own words repeating throughout.

Consider how protagonist Holden Caulfield, an American reprobate of a teenager, is talking about death and loneliness in The Catcher In The Rye, circa 1951.

Holden Caulfield

When you’re dead, they really fix you up. I hope to hell when I do die somebody has sense enough to just dump me in the river or something. Anything except sticking me in a goddam cemetery. People coming and putting a bunch of flowers on your stomach on Sunday, and all that crap. Who wants flowers when you’re dead? Nobody.

Compare that to this passage, where the delicate English lady Lucy Snowe works in loneliness in France, in the 1800s,

If there are words and wrongs like knives, whose deep inflicted lacerations never heal – cutting injuries and insults of serrated and poison-dripping edge – so, too, there are consolations of tone too fine for the ear not fondly and for ever to retain their echo: caressing kindnesses – loved, lingered over through a whole life, recalled with unfaded tenderness, and answering the call with undimmed shine, out of that raven cloud foreshadowing Death himself.

3. Accent

What accents do your characters have? Is it essential to convey the accent by writing the words phonetically? Writer Irvine Welsh does just that, writing in a thick Scottish accent, but it may be hard for some readers to grasp. Despite that, he’s a hugely popular and successful author. Here’s an extract from Trainspotting:

Society invents a spurious convoluted logic tae absorb and change people whae’s behaviour is outside its mainstream. Suppose that ah ken aw the pros and cons, know that ah’m gaunnae huv a short life, am ah sound mind, ectetera, ectetera, but still want tae use smack? They won’t let ye dae it. They won’t let ye dae it, because it’s seen as a sign ay thir ain failure. The fact that ye jist simply choose tae reject whut they huv tae offer.

Maybe it would be easier not to write in an accent. Instead, you could say, “she said, in a thick Scottish accent.” But maybe not as fun.

4. Roots

Where were your characters born? Maybe now they live in Los Angeles, but they were born in New York. Maybe they are a famous movie star now, but they were once a gang member in Detroit. Maybe they have a French mother, or a Jewish grandfather. What is it about your character’s vocabulary that betrays their roots? Perhaps, like me, they call a mess a “schmozel” because they have heard Yiddish in their family. Or perhaps they say, “What you on about?” like my American husband does nowawdays after years of being with a Brit. Give your characters backstory.

Not really having it all.

5. Experience

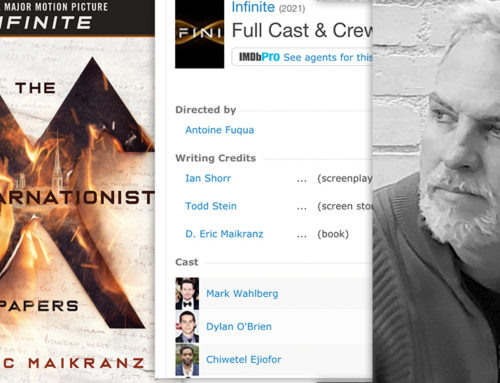

Characters are sometimes written so incredibly passionately by a writer that they end up being over-experienced and under-voiced. Let’s look at a book I once edited. An international spy who used to be a top attorney in Washington travels from the Caribbean to Iceland on a mission to save a top secret document. He stops to have dinner with the President’s translator. They are discussing the local mall’s cut-price socks and panties offer over drinks, having just spoken flawless French with the wine waiter… Give your characters the intelligence they deserve and talk politics, literature, science, or art.

I have edited many books where characters that “have it all” (my bugbear phrase), including traits such as having a diving teacher license, a pilot license, a doctorate from Harvard and the looks of a beauty queen, are the biggest dullards going.

The same is true when children are talking together: normal, having-fun children can descend into rhetoric, nuance and sarcasm despite being under seven years old. If in doubt, watch some documentaries on YouTube or some Ted Talks to boost your own character experience level knowledge.

6. Age

This can be a make or break. Authors can forget the age of a character and the nuances of speech. Would a granny in her eighties say “what a blast!” ? Maybe if she were a sassy granny from New Jersey. Maybe not if she’s a refined dowager in 1800s England. Would a child say they’ve lost their “dignity?” More likely they’d say they were “embarrassed” or “shy to” do something. Don’t let your own age group peek out at the reader.

7. Swearing

How does swearing suit your character’s experience and background in life? Do they change their quantity of swearing when they are with certain others, or are they the same whoever they talk to? For instance, a beggar may swear with his wife, but not with the kindly priest who gives him bread. There are many books with delicate, classy women characters that have them swearing like troopers. The opposite is also true, that the author’s strong view about swearing can come into play and have a book about troopers with no swearing!

Let’s try this, from the script for the movie “Platoon.”

Sgt. Barnes: Y’all take a good look at this lump of shit. Remember what it looks like. You fuck up in a firefight and I goddamn guarantee you a trip out of the bush in a body bag! Out here, assholes, you keep your shit wired tight at all times!

[to Taylor]

Sgt. Barnes: And that goes for you, shit-for-brains. You don’t sleep on no fucking ambush!

[to Junior]

Sgt. Barnes: And the next son of a bitch I catch copping “Z”s in the bush, I’m personally gonna take an interest in seeing him suffer. I shit you not. Doc, tag him and bag him.

Without the swearing:

Sgt. Barnes: Y’all take a good look at this one. Remember what it looks like. You mess up in a firefight and I guarantee you a trip out of the bush in a body bag! Out here, you lot, you keep yourselves wired tight at all times!

[to Taylor]

Sgt. Barnes: And that goes for you, too. You don’t sleep on no ambush!

[to Junior]

Sgt. Barnes: And the next one I catch copping “Z”s in the bush, I’m personally gonna take an interest in seeing him suffer. I kid you not. Doc, tag him and bag him.

Seems tame, doesn’t it? All the tension is pushed out of the dialogue. Suddenly it reads like rather refined scouts on a camping trip.

However moral a viewpoint, cursing needs to be realistic to your character. Also, if you are writing a fantasy novel or futuristic novel, you may want to consider my point about vocabulary. Historical novels need checking for swearwords that maybe didn’t exist back then. Although you’d be surprised by what did…

The words you use around your character’s voice are just as important. These are known as “dialogue tags”. These should be used sparingly, and only to enhance a scene. If in doubt, the rule of thumb is “show not tell.” Use action to explain mood. Stick to “said” or “asked” because these types of generic tags are more obsequious and tend to remain unobtrusive to the writing. Click the image for an infographic that gives you 100 ways to say “said” from Write At Home.

When should you use different tags? One book I read recently had nearly every character “giggling” :

“Oh, yes!” she giggled.

“I’ll be there!” the policeman giggled.

See how wrong that seems? Now try this:

“Oh, yes!” she giggled.

“I’ll be there!” the policeman said.

Here, the policeman feels in control and well, like a policeman.

Here’s another example where dialogue tags are needed.

“You go that way and I’ll look for the suspect over here!” Margot said over the roar of the crowd in the stadium.

“OK, take care, he’s armed, remember!” the sheriff said back, not sure she could hear him as the home team scored a goal.

While it’s not terrible, dialogue tags would enhance the exchange:

“You go that way and I’ll look for the suspect over here!” Margot shouted over the roar of the crowd in the stadium.

“OK, take care, he’s armed, remember!” the sheriff yelled back, not sure she could hear him as the home team scored a goal.

Here’s an example of action over tags:

The girl rose from the flames, commandeering her people as she said, “I am your queen!”

Let’s try that with a dialogue tag:

The girl rose from the flames. “I am your queen!” she commandeered her people.

In the end, it might be a case of taste and style, but bear in mind your options.

Cate Baum is the book editor at SPR. You can get your book edited here.

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Society invents a spurious convoluted logic tae absorb and change people whae’s behaviour is outside its mainstream. Suppose that ah ken aw the pros and cons, know that ah’m gaunnae huv a short life, am ah sound mind, ectetera, ectetera, but still want tae use smack? They won’t let ye dae it. They won’t let ye dae it, because it’s seen as a sign ay thir ain failure. The fact that ye jist simply choose tae reject whut they huv tae offer.

Society invents a spurious convoluted logic tae absorb and change people whae’s behaviour is outside its mainstream. Suppose that ah ken aw the pros and cons, know that ah’m gaunnae huv a short life, am ah sound mind, ectetera, ectetera, but still want tae use smack? They won’t let ye dae it. They won’t let ye dae it, because it’s seen as a sign ay thir ain failure. The fact that ye jist simply choose tae reject whut they huv tae offer.

Leave A Comment