Cate Baum – Editor

It’s time again. Cate Baum, SPR Editor is back to enlighten writers everywhere on how not to drive their editors up the wall.

Here, I have listed my top bugbears uncovered editing self-published works from around the world. Enjoy, learn, share. If you want to find out more about our editing services tailored to the needs of self-published authors, have a look here.

1. The word “OK”/Ok/Okay

The most overused word in most books I see today, especially from American writers. The most common spelling it seems, for some unknown reason (I’m blaming texting and tweeting) is “Ok”. I have just corrected this in a manuscript 648 times. Imagine!

Let’s get this straight. “Ok” is half a word. The way we spell this pet hate of mine is “okay” or “OK”. The word “okay” is a verb. People also use it as an affirmation, “Okay then.” I will accept “OK then.” at this juncture. “OK” is a term of speech, and for more modern, zippy work it’s mildly acceptable. Style comes into it, too.

For the most part, I will always edit a book with the full spelling of “okay”, but leave “OK” if it’s in speech – and consistently used by the author. However, if I see this word in a book set in the past in certain countries, I have to check the history books, because it originates in the “mid 19th century (originally US): probably an abbreviation of orl korrect, humorous form of all correct, popularized as a slogan during President Van Buren’s re-election campaign of 1840 in the US; his nickname Old Kinderhook (derived from his birthplace) provided the initials,” according to Google.

2. Paragraphs

When faced with a page of dialogue interspersed with descriptive passages, I am astounded by the amount of clients who don’t understand how to space their work. I spend most of a proofread edit formatting these. Here’s the skinny. You have choices, but some rules.

When someone new starts speaking, you need to be on a new, indented line. If your character is described doing something and then speaks, you don’t have to go to a new line unless you want to, or until the speaker or described action changes:

Chris was tired. He put his keys down on the table. “What’s for dinner?” he asked.

“Oh I forgot to make it!” said Cindy.

When you change times, such as “Half an hour later…” start a new line. When you start a new train of thought, start a new line.

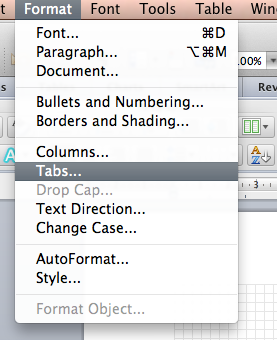

There are a few ways to indent a paragraph in Word. You can set your tabs by going to Format > Tabs and set the indent you want. I wouldn’t go above 1.7 here:

However, it might be a good idea not to use tabs when you are formatting for e-book publication. I usually remove and replace all tabs with an indent in my e-books by doing the following:

- “Find/Replace” and using the symbol “^t” in “Find”, with nothing in “Replace” and then “Replace All”. This removes all tabs.

- Then go to Format > Paragraph > Indents And Spacing tab.

- In Indention, choose “First Line” from “Special”

- Choose the size of the indent in “By”

- Click OK.

3. Using foreign languages in your book

It’s all very well using the odd “Monsieur” or “As-salamu alaykum” to give a book flavor; most readers know what these mean even if they never took a language at school. But don’t bind your readers to a paragraph of schoolboy Spanish! For a start, you’ll have to get it native-correct. Lucky for me I speak several languages well enough to fix errors in grammar, but I do end up fixing a lot of errors.

The only reason I would use a foreign word without explanation is to alienate readers on purpose, maybe to create the feeling of “a fish out of water” as your character struggles to fit into a new country, for example, or because the word is meant to be not understood from the character’s perspective, in order to uphold the plot of the book. Otherwise, it’s plain showing off.

4. The Ellipsis (again)

Just remember it’s dot-dot-dot…and nothing else. More dots don’t make more pauses.

5. Capitalizing after speech

This one makes me want to scream. Mostly because Word’s spellchecker (and other autocheckers on the market) loves to make this wrong. Let’s get this straight – Word is not your bar. It’s a guide, and often that guide is incorrect in certain situations.

Do not capitalize after speech marks. It seems wrong in our internet-weary, short-attention-spanned minds. Despite what punctuation is in speech marks, you should follow like this:

“Hi, can I speak to you?” said Danny, “I need some help.”

“Whatever happens,” said Jill, “I’m here to help you.”

“Thanks!” he said, warmly.

6. Their/They’re, It’s/Its

Why is it so difficult? Maybe because writers need to read many more good books than they do. Hearing language, and not seeing usage regularly enough in print can lead to this phenomenon. We all know the truth about these words, but get lazy about using them properly. It’s been getting worse lately as we take in so much unedited guff online.

Let’s recap.

Their – Possessive. “Their coats are on the hook.”

They’re – Short for “They are”, denoted by the apostrophe “‘”. “They’re on the hook.”

It’s – Short for “It is”, denoted by the apostrophe “‘”. “It’s too cold outside for the baby’s ears.”

Its – Possessive, when we don’t know the gender of an animal, creature, or baby. “It’s too cold outside for its ears.”

7. Characterization

Characters so vain and impossibly perfect are all the rage

It happens again and again. I read about these characters and I can’t believe them. Why? Let’s look at a few examples of recent times.

Brad (we’ll call him Brad) is a pilot with a muscular but trim body, looks 25 but he’s 40. He’s got perfect teeth and exudes sexuality with his thick blond hair and deep blue eyes. When he was ten he won a national wrestling contest. At eleven he graduated high school. He’s got a degree in cryptology from Harvard, for which he was national first, and was top of his class when he took his PHd in Astrophysics. He served in two wars and won eighteen medals. He’s also kind, caring and sensitive and amazing in bed. He speaks seven languages. His parents couldn’t be prouder and he has a great relationship with everyone. He is the most popular everywhere he goes.

Daphne (we’ll call her Daphne) is sure of herself and knows she has perfect breasts, athletic but slim legs, thick lustrous black hair, the most unusual eyes in the world, a husky voice, looks 30 but is 45, speaks four languages despite growing up in Ohio, where she won a scholarship to study engineering (she came first) before becoming a businesswoman refurbing furniture, for which she is now a millionaire. She has six kids and three lovers. She’s a tennis champion and a fantastic gourmet chef. All her kids are gifted and look like models. She’s amazing in bed.

Do these people feel real outside of Baywatch or The OC to you? Do you like them as people to relate to?

Despite all these “genius supermodel” traits, the way these characters speak and act matches a medium-intelligence, untraveled and naive set of behaviors. In other words, the writer has no experience of being the characters they have written, and has done no research.

8. Character Reaction/Action

Easier to ignore the character’s reaction?

Another example of bad characterization comes from reaction/action. Would a woman who had just been raped be talking about the way her hair is a mess? Would her father be commenting on the nurse’s looks? Would a man whose wife just got murdered in front of him be eating a hot dog? Would that same man in the next scene be fine, like nothing happened, and never mention it again? You’d think not. But apparently, these characters can have no reaction whatsoever, and it’s fine.

Fiction editor Beth Hill says,

A character does not need to reveal his response overtly to other characters, of course. But if he has no response—if the reader can’t see a response of any kind—then there isn’t one. Characters can keep their emotions hidden from other characters but not from readers. A response hidden from the reader is the same as no response.

9. Lack of Research

I have had all kinds.

- A captain that sails up to Seville along the river in a ship then jumps into the bullring (Seville’s bullring is on the other side of the road to the Guadalquivir)

Seville’s Bullring – Quite a jump from the river…

- A writer in London who runs from Big Ben to his office in Brixton, taking five minutes to get there (This is an hour by bus)

- A woman who irons a mound of clothes while her husband is out feeding the pigs, 1442, England (the flatiron was invented in 1882, and most families at this time would have had maybe one or two outfits if they were lucky)

- Talking about “black sand” on Santa Monica Beach, Los Angeles. This beach has yellow sand.

The point being, I only had to Google these points to find out they were incorrect. Using Wikipedia and Google Maps is essential to check facts at the very least before writing them down. Street View and Google Earth can prove invaluable for checking locations, as can local travel sites. My advice is “write what you know”. Travel to places and take photos. Use hard copy books in reference libraries, and museums to research instead of the internet, because “online facts” can be wrong with no governance.

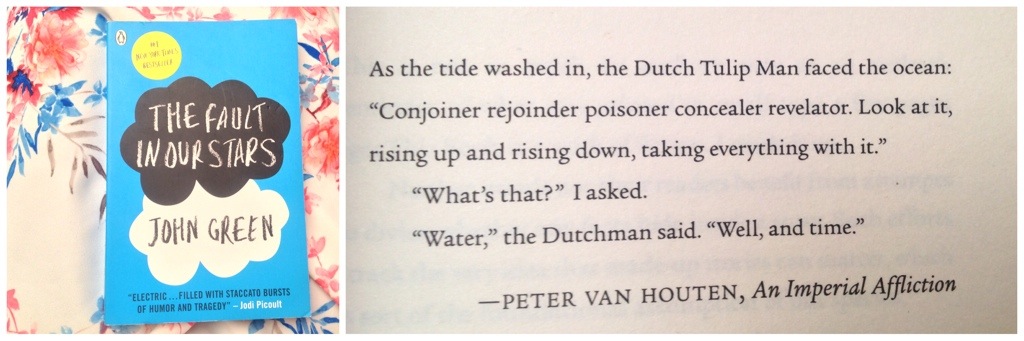

10. Epigraphs

“An epigraph is a brief, interesting, memorable, and sometimes surprising or satirical statement.” Wikipedia

When you write a book, think about this. Do you really need to add an epigraph? Employing this literary device isn’t always a good idea. Ask yourself why you want to quote your favorite band, writer or poem. Is it going to add to your work, or could it detract something? After all, quoting Shakespeare ahead of your own writing could be a bit like taking your best-looking friend on a date-hunting mission to the local disco – will the beauty of your epigraph show up your literary zits and extra flab? Mostly, yes.

Could the mysterious allure of your epigraph show you might also be alluring and mysterious by association? Maybe a little. In the right light. But please, steer clear of the following, for cliche’s sake: HG Wells, Shakespeare, Gandhi, Mandela, Luther King, Oscar Wilde, The Bible, Lewis Carroll, Pope, Greg Packer, Steve Jobs. I cannot tell you how many times…

And one last note: Please don’t use Goodreads to look up quotes. They may not even be correct. I have seen many incorrect quotes on there, shamelessly flanked by the correct quote. “Which one?” you cry, hopelessly Googling the quote, and both variations showing up…Ah, for the days of dusty library research. Nothing went wrong there. (Except books having pages torn out. At least that’s how it was in England’s East Anglia’s backwater village libraries where I grew up; grey affairs of prefab origins with posters of dancing toothpastes and road safety squirrels guarding the microfiche and several copies of Who’s Who.) Check the actual book you want to quote, and get permission if necessary.

A faux epigraph from John Green’s “The Fault In Our Stars”

My favorite style of epigraph, such as in “The Fault In Our Stars” by John Green or “Cloud Atlas” by David Mitchell, is the faux epigraph. These epigrams are quotes from characters’ works inside the novel itself. Think about this; it’s a lovely and original way to step into a book’s world.

If you would like to submit your book for editing or proofreading take a look here.

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Good advice. I’ll add another. Avoid the hassles and meddlesome intrusiveness of Microsoft Word by using an app such as Scrivener which is specifically designed for writers. Versions for Macs, Windows and (soon) iPads here:

http://www.literatureandlatte.com/scrivener.php

I’m not sure if I would undertake some writing projects without it. It is that good.

–Mike Perry, co-author of Lily’s Ride

I’m so glad my books don’t have these kinks. I’d like to suggest more basic stuff, like the use of hyphens. I’ve seen people completely avoid them. I rather like the look of hyphens in a manuscript, self-control, blue-footed booby, etc.

Also, don’t depend on the spellchecker. It may be spelled correctly but be absolutely the wrong word.