Cate Baum – Editor, SPR

Following on from my last article about editing, I thought it was about time we tackled some more bugbears uncovered in my most recent journeys into the self-published world I tend to inhabit these days.

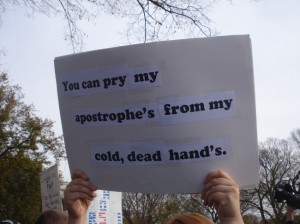

1. The “s” – Plural usage vs. Possession

For some unknown reason, some writers grow up and make life complicated for themselves with plurals. Often I walk by stores advertising “tomato’s” and “offer’s”. When we were kids at school, we all knew to make something plural you add an “s”. This all seems to fall by the wayside for some of us some of the time because maybe people get scared of the apostrophe. Do you put one in? Leave it out? Ah, what the heck. Throw one in. Well, no. You want to be a writer. So…

Here are the main rules I see broken time and time again.

a. Use the apostrophe when you need to show something belongs to someone, called possession. A singular noun, e.g. “teacher”, “dog”, “camp”, needs an apostrophe plus the letter s.

- The teacher’s apple

- The dog’s bone

- The camp’s clubhouse

When a word ends in an “s”, such as “class” or “bus” , there is a choice to either add an apostrophe and no “s” after it, or add both an apostrophe and an “s”. Whether you choose one method or another, stick to it throughout your work. - The class’ schedule

- The bus’s driver

b. If a person’s name ends in an “s”, the same rule applies, but make sure you put your apostrophe after the person’s full name, and not before the “s”:

- Mr. Jones’ car

- Miles’s bike

- Chris’ necklace

You maybe could see how the word sounds spoken before choosing your method. For instance, “Jones'” may sound better to you than “Jones’s – this form sounds like “Jones-es”. If I was a Jones, I’d be sick of the trope “Keeping up…”

c. Never use an apostrophe with a plural: “Blue Moon’s” should be “Blue Moons”. However, the exception to the rule is when a word that is not usually plural is used, such as “do” or “no”. These will then become “do’s” and “no’s”.

d. Irregular noun plurals need to be treated as if they are singular. The plural of “child” is not “childs”, but “children.” The plural of “sheep” is “sheep”. Therefore, the apostrophe is used in possession like so:

- The children’s things

- The six sheep’s food

There are many, many more rules to do with letters, numbers, groups etc. but there are the main offenders. Click The Oatmeal image, right, for more.

2. The Homophone

Some of the classics I have come across lately are:

- To all intense and purposes – I’m sure it could be intense to use this phrase, be it should be “intents and purposes”.

- He was adulteress – He’s not a she, so he’s not an adulteress, plus this is a noun. Therefore this should be “adulterous”.

- The bells were peeling out across the village – We’d best take cover, if lumps of paint are falling! This should be “pealing”.

- He wasn’t phased by her tone – He wasn’t rolled out in stages? Maybe he wasn’t fazed then.

So if you name something in your fictional world, you need to make a decision on that name. Is it a brand? Is it a company? A tribe? Capitalization needs to happen in certain situations in our world, and therefore that convention needs to be carried over into your new one. Brand names, company names, organizations, drugs, institutions, planets (but not the moon or the sun), religions and nicknames all need capitalization even if they are not real – but note, while religious books are capitalized, whether real or fake, heaven and hell are not – and capitalizing gods, including the Christian “God” is a matter of choice and faith. Here’s a passage I knocked up to show this:

In the city of Carth, ten Niam slaves bowed to the king at the foot of Mount Carbart. King Jamish turned to his knight, Hamiip “Ten Tigers” Mako to ask his advice. When the planets of Jupiter and Mars passed the moon and the city entered the Quake Era, they would be ready to start the National Competitions that Carth was so famous for. Many of these Niam were of the Dion religion, and they were willing to die and go to heaven for their beliefs.

4. The Heteronym

Often, this bothersome linguistic fool stays away from writing. A heteronym is a word that remains spelled the same, but that has more than one meaning. However, occasionally it’s a real nuisance to a sentence. And then, some writers don’t bother to restructure the sentence to accommodate it. Here are some examples from real books that really don’t need to twist the reading eye:

Often, this bothersome linguistic fool stays away from writing. A heteronym is a word that remains spelled the same, but that has more than one meaning. However, occasionally it’s a real nuisance to a sentence. And then, some writers don’t bother to restructure the sentence to accommodate it. Here are some examples from real books that really don’t need to twist the reading eye:

- I was not close enough to close it – why not say, “I was too far away to close it” so your reader doesn’t do a double take?

- The wind was so strong I could not wind in the kite – Why not say, “pull in” to rest the eyes?

- The bass was thumping on the floor – Well, this is about a fish dying. But the word “thumping” leads the reader to associate this bass with the music kind. “Flapping on the floor” would keep this word fishy.

- The woodsman bowed, his bow on his back – can’t his quiver be on his back? His bow is in his hand most likely anyway.

A sentence with more than one subject and verb with nothing to separate the phrasing needs fixing. Using the humble comma “splice” or well-placed period can help you out amazingly. Again, real-life examples show this issue:

He reached for his shake made with all the alien fruit he could lay his hands on even though Gara had warned him of the side-effects of some of these berries for humans.

could be:

He reached for the shake, made with all the alien fruit he could lay his hands on, even though Gara had warned him of the side-effects of some of these berries for humans.

Another example:

Kelly ran for the door knowing full well on the other side there was only misery for her when she made it to the new world without Toby as she hadn’t planned to be alone.

could be slightly rewritten:

Kelly ran for the door, knowing full well on the other side there was only misery for her when she made it to the new world without Toby. She hadn’t planned to be alone.

Personally, I think fragments are fine used sparingly for poetic effect.

Unless you are writing a way-out-there book, or some kind of Beat prose, please stick to one tense. There’s a few to choose from, but the main three are Past, Present, Future – sorry if I am being a little trite, but the things I’ve seen…

The choice is simple: if you want to get your reader running through dangerous forests and battle sequences and thinking on their feet with your character, you may want to use present tense. The Hunger Games Trilogy uses this technique to great effect, as does the dreaded Fifty Shades series if you like that kind of stuff.

Fight Club is probably the most famous book written in present tense. Why is it in present tense? Because The Narrator doesn’t know he is Tyler Durden, and he shoots himself in the end. So he can’t very well be telling us the story in the past tense. So have a good reason to write in present tense, because otherwise you could end up making your book look a bit – well, pretentious.

To me, however, past tense will always be more literary, more beautiful, and affords you both back story and room for regret and memories etc.

Future tense is going to be weird in a book unless it’s a prediction. The Bible, for example does it, as do some science and pseudo-science books. There isn’t much call for it otherwise.

But whatever you do, don’t go mixing it up unless there’s a really good reason for it. Here’s an example of a mix-up:

When I saw the coast it was beautiful. Tarifa mixes curling blue waves with foamy backs on a white sand that I love.

OK. That’s fine, but this can only really work if the character is introduced as narrating a memoir and is older in the beginning of the book, or maybe the book is a non-fiction account of traveling to Spain. Writing in this way can somehow break the fourth wall for the reader. It is a matter of taste, and it has to be dealt with well or not at all. Is it necessary to force your reader out of the scene to give them a quick bite of information?

Or can it be:

When I saw the coast it was beautiful. Tarifa mixed curling blue waves with foamy backs on a white sand, a combination that I grew to love.

I will return with more findings anon.

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Leave A Comment