Melissa McPhail is a classically trained pianist, violinist and composer, a Vinyasa yoga instructor, and an avid Fantasy reader. A long-time student of philosophy, she is passionate about the Fantasy genre because of its inherent philosophical explorations. For this interview, we focus on the author’s selection and use of languages in creating a world for her fantasy series, A Pattern of Shadow & Light. Our story is set in the mythical realm of Alorin, three centuries after a massive war which almost wiped out an entire race called the Adepts.

SELF-PUBLISHING REVIEW: In my SPR review of Cephrael’s Hand, Book One in your series, I labeled it Epic High Fantasy, with Epic referring to a mythology the characters will play out and High referring to a fictional world you create for these characters to live in. I’m generalizing these definitions, of course, but I’m curious, did your characters come to you first, or did their world?

SELF-PUBLISHING REVIEW: In my SPR review of Cephrael’s Hand, Book One in your series, I labeled it Epic High Fantasy, with Epic referring to a mythology the characters will play out and High referring to a fictional world you create for these characters to live in. I’m generalizing these definitions, of course, but I’m curious, did your characters come to you first, or did their world?

MELISSA McPHAIL: My characters are definitely the driving force of the story, and they’ve anchored it, as much as my interest in it, since the beginning. The world changed around them many times as I reworked the plot and expanded the nature of the conflict, but the core viewpoint characters barely altered from their original personalities. First came the characters, and the world had to evolve until it gained enough detail (and cast enough shadows) to become an adequate field for their stories.

This is simply my instinctive approach. It’s more natural for me to start with a character, a solitary point, and spin out the story linearly from his viewpoint, than to craft the broad world and then go back to fill in the details. The world is only interesting because of the characters’ interaction with it.

SPR: Ah, so let’s talk about this passage:

In the desert tongue, a simple phrase had a plethora of meanings—meanings often derived from the parable in which the phrase was first used, thereby necessitating an understanding of the kingdom’s history as well as the language itself. With the common tongue, in contrast, a plethora of words were used in place of a simple phrase. Thus, though it wasn’t his first language, Trell had come to find the implicit desert tongue far more appealing than its explicit counterpart—as any thoughtful, scholarly mind would, he felt.

In terms of your creative process, then, Trell of the Tides is a philosopher by nature, thus needing a philosophical language to be drawn to?

MM: Yes, you could certainly say that. Trell is a thoughtful, introspective character, and it would follow that he would notice this type of difference between two languages he spoke well.

Trell’s view of the desert tongue comes from his experience in learning it. In order to teach someone to speak the language fluently, it is necessary to tell them the history of the land.

I’m intrigued by the way languages are created. The desert tongue derives from the combined language of nomadic tribes—warriors, not scholars. There are parallels to the Native American languages in terms of customs and ceremonies (as well as superstitions and religious beliefs) incorporated into the language. It is a spoken language more than a written one, and therefore draws upon the stories of its history in defining terms and use.

SPR: Yes, that’s what I got from this passage:

He knew just from speaking the common tongue that the culture of its peoples was very different. In the desert, as in the language itself, there were nuances—huge disparities, actually—in what was said and what was understood.

SPR: My impression is that Trell’s thoughts about the two languages mirror his questions of origination and identity that are part of his quest to solve, that he is part of two cultures.

MM: You’re very perceptive to Trell’s state of mind. His conflict with the languages is certainly a harmonic of the struggle he feels over choosing a side. Though he has not yet been forced to do so, he fears—and rightly—that his family’s allegiances lie elsewhere than the Akkad. While inclining toward a philosophical language as a natural extension of his general outlook, were he to examine this viewpoint, even as you have, he would wonder if he leaned toward the Akkadian language—not because it is inherently implicit and therefore kin to his own nature, but rather in an attempt to avoid the fear that his native tongue held painful associations, that it was too closely associated with whatever tragedy (of birth or act) brought him to the palace of the Emir. The very fact of his nobility, though hidden from his knowledge, causes him to constantly question it.

SPR: I want to ask about Old Alaeic, the mother language of what is called the Common tongue of the northern regions. An example is the phrase ma dieul tan cyr im’avec. Did you invent this Old Alaeic language, or is it a derivative of one of our Earthly languages?

MM: Old Alaeic is one of several languages used in the novel. It has the longest history of any language in the story, dating back to the Sobra I’ternin. It isn’t a dead language, such as Sanskrit, since some are still able to speak it (notably among them those sworn to the First Lord), but like Sanskrit, it is mostly a written language now.

I didn’t base Old Alaeic on any earth language, but it is similar to Sanskrit in that only certain types of words derive from it—mostly those concerning Adepts, the varied Adept races, and the use of elae. It is one of three root languages to the common tongue, along with Cyrenaic and Veneisean (that last two of which are based on earth languages). Occasionally we’ll find other languages feeding the common tongue as well, but more rarely. Like English, it’s a hodgepodge of different dialects and tongues spoken by the early settlers of the northern kingdoms.

The desert tongue is based on a combination of Turkish and Farsi with some Arabic mixed in.

SPR: How many languages are spoken in Alorin? Will there be additional languages introduced in Book Two or have we “heard” them all in Book One?

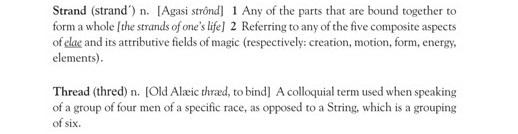

MM: There are seven languages discussed in the series, either in the first or in subsequent books: The common tongue, Old Alaeic, the desert tongue, Veneisean, Sevillian, Cyrenaic and Agasi.

Old Alaeic is the language of the Sobra I’ternin and the angiel. It is spoken among a few, including the Empress of Agasan and her Consort, the drachwyr and zanthyrs, and others sworn to the First Lord. Because it is the language of the Sobra I’ternin, it is studied by many scholars but widely considered a dead language.

Cyrenaic is still spoken in Vest and parts of Avatar (we’ll introduce this language in Book 3) and is a root for the common tongue.

The common tongue is the trading tongue. Like our English, it is spoken around the realm. It is derived most closely from Old Alaeic but also has root words from other languages.

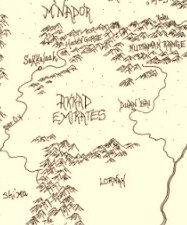

The desert tongue, of which there are several dialects, is spoken in the Akkad, M’Nador, Kandori, Avatar and Saldaria. It is unclear whether the tribes of the Akkad were settled by the Avataren and absorbed their language, or the other way around. The oral histories of both peoples claim origin. Most likely the language spread with the Cyrene Empire, who opened a slave trade to Avatar several millennia ago.

Veneisean is spoken widely among the educated.

No new languages are introduced in book 2, but in book 3, we’ll be introduced to Sevillian, the language of Rimaldi; and Agasi, which is a blend of New Alaeic (the spoken Language of the Scholars) and Sevillian.

Many cultures still have their own tongues, some of which are mentioned in book 2 but not introduced (in terms of actual words), specifically the Bemothi, the Fhorgs, and the Danes.

SPR: I’m not seeing “language scholar” in your bio, yet you draw convincingly on a variety of languages in creating the cultures coexisting in Alorin.

MM: Thank you, Lela. Not being a languages scholar, I’m relieved you found them convincing.

It’s important to me to convey the world of Alorin with as much depth as possible. Obviously languages play a vital role in that process. They help define and give shape to a culture, and they bring a breadth of outlook to the world and alter the reader’s experience in it. I’m always on the lookout for opportunities to plug in new details that add texture without slowing down the pace of the story, and language can be helpful in that regard.

I can’t honestly say I put much thought into planning the languages ahead of actually writing the story. The desert tongue began with “Khoob, that is well for the sun,” an off-hand comment that floated in on the current of author creation. Yet even as I wrote it, my concept of the language started taking shape, and the details of it became clearer thereafter.

SPR: So language contains and reflects history; history is reflected in the cultural practices, beliefs, and motivations of your characters; and your characters came to you first in your creative process. With that, I feel we’ve come full circle. Is there anything about the languages in Alorin that we didn’t touch on that you’d like to add, anything you were especially pleased with or exceptionally frustrated about with regard to world-building?

MM: I think the hardest part was developing the colloquialisms of the desert tongue, such as “only the wind knows the truth in the water.” In fashioning them, I had to take into account that they would be given to the reader translated from their original language, which condition, I’ve found, makes many sayings either meaningless or hopelessly confusing. So it was challenging to create these, yet fun at the same time.

Thank you so much for the interview, Lela, and for your many thought-provoking questions. It’s been a wonderful experience exploring my story from such a specific viewpoint.

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Thank you for this insightful article! I am one of Melissa’s biggest fans – I’ve read “Cephrael’s Hand” twice, and have been privileged to read a draft of “Dagger of Adendigaeth.” (Fans are in for a real treat when that comes out!) This article gave me a deeper insight into the realm of Alorin, it’s development and its depth, which helps me appreciate this epic series even more. Great job!

As evidence of the convincing languages–I paid no attention to them except to notice some of the prettier, although hard to pronounce, pieces of Old Alaeic.

I’ve read “Cephrael’s Hand” once and I’m in the middle of reading it again. I’ve never–although I haven’t read every book out there by any means–read a more intelligently written book. “Cephrael’s Hand” is never clichéd, always interesting and impossible to put down.

Thank you for the article and interview. I really enjoyed Cephrael’s Hand. Melissa commented on this in your interview and it really feels true as a reader; her characters really create the story – they drive the story versus the story including them. Her use of lanugage and hearing her discuss the depth of research really evidences the depth of this great book. I can’t wait for the rest of the series!!!

What a joy to read a well prepared and thoughtful article that begins to reveal the work it took Melissa to write this wonderful story. We learn that this small look at the discussion of the role of language in the writing took on a life of its own. Like all great writers, it is the passion of the work that drives the will to create avenues that take on their own life. Well done Lela, exceptional insight into the work you did to create this success Melissa. I look forward to more excellence in the work to come.