With big publishing buying only the crème de la crème of books, and more authors turning to self-publishing, many literary agents are getting squeezed right out of the middle.

But some savvy agents are acting as literary consultants to help their authors self-publish, a role that offers up new opportunities and challenges for everybody in the industry.

I talked with three agents about their experiments to serve authors by widening their middle ground.

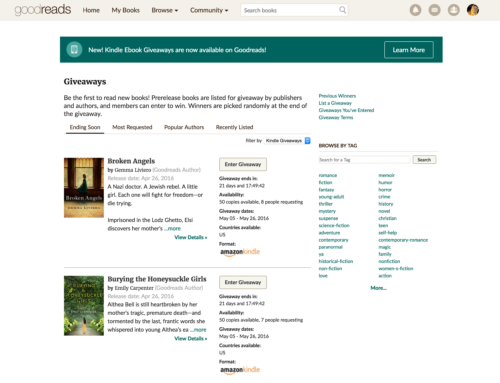

Ted Weinstein (left), a San Francisco-based agent who represents non-fiction authors, said that self-publishing “has added one more serious option for my clients when we are looking at all their possible opportunities.” He’s currently working with authors he has successfully placed with traditional publishers “to launch additional mid-length material and backlisted books using new self-publishing tools.” These tools include Amazon’s CreateSpace and Kindle Direct Publishing, Barnes & Noble’s PubIt, Smashwords, and more.

What this amounts to is agents turning into a kind of Author Solutions company – offering things that a writer could pull off on his or her own, but a one-stop place for certain services, including consulting. Moral: it’s as hard out there for people in the traditional publishing industry as it is for writers.

This is amusing (emphasis added):

Rennert shopped “Solstice” to traditional publishers, and it even went to acquisitions at one house. She said that when it was finally rejected (because it was too similar to another book being published by a big name house), “we realized this was a concern we were likely going to run into elsewhere, so Hoover made the choice, in consultation with me, to go the independent publishing route and be the first to work with our agency in this capacity.”

This goes out to all those people arguing about independent vs. self-publishing. Give in already, independent publishing has a new meaning (and I’m a person who always uses the term self-publishing). Agents are now using the phrase for the same reason that writers are: to soften the blow and make it seem more legitimate, so it’s a term that’s going to stick.

Meanwhile: AAA will not expel agents turned publishers:

The Association of Authors Agents will not expel those agents who have begun publishing their clients’ work, after a meeting of agents held last night came to what one agent described as a ‘consensus’ that it was not a conflict of interest.

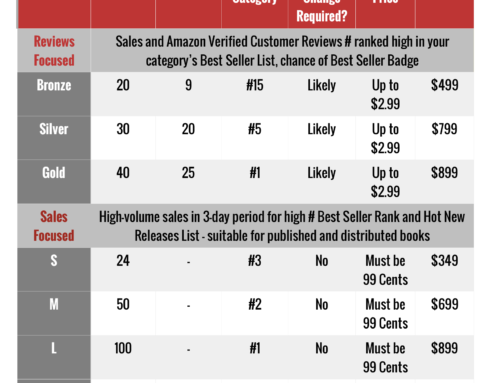

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

This has been a pretty live issue in the UK in the past couple of weeks. The below blog piece is UK literary agent, Peter cox, and his rebuke to agencies setting up imprints for backlist titles for ebook. Directing authors to services like CreateSpace etc for books reverted back to the author is a little less a ‘sensitive’ issue.

http://mickrooney.blogspot.com/2011/06/redhammers-peter-cox-slams-agencies.html

Thanks, Mick. I was going to write something about this, but couldn’t get my head entirely around it. At what point is it considered “publishing”? If an agent advises that a writer publishes to the Kindle and then takes 15% off the 30-70% is that “publishing”? For writers, publishing to the Kindle is considered self-publishing, but for consultants it might not be. It’s a bit different than setting up an imprint of Agent X publishing. The agents in the Media Shift article appear to mainly be participating in the former.

This is a absolute minefield, Henry.

As an agent, Peter Cox believes agents should not set up imprints to publish their clients books out of rights. He believes the line of agent/publisher should not be crossed. Agents should represent their authors, and deal with publishing avenues on behalf of the author. But yes, you’ve made a valid point. If an author with agent, who decides to use Amazon Kindle, have to concede 15% to the agent on the 70/30 deal. Personally, no, the agent did no work for their commission. Their 15% (or whatever) is based on a deal brokered by the agent with the third party.

Agents make their money on the sign-on deal with a publisher – which is why agents are reluctant to deal with an author who, after a book release, pedals short stories or poetry unless it is with a high-paying magazine or newspaper. Their paycheck is publishing deals, foreign rights, book clubs, translation etc. (So, no, if a book is free to sell rights, and the author negotiates with Amazon, or whoever, then the agent has no hand in that unless the authors says – yes do it – find an ebook deal)

Cox’s argument is that agents should never become publishers, because there is a conflict of interest. This becomes a ‘new’ uncontracted stream of revenue for the publisher and profit leads to their interests in the author being divided.

If I understand Cox to a point, he is concerned that the agent creams profit from the publisher/agent deal, and then seeks to follow up by creaming profit from the author/third-party deal without having to do very much. In the self-publishing world – we call that double-dipping – taking profit from the author to set up the title, and then a further profit from print mark-ups and every sale of the book.

So what do these new agents do for unknown independently publishing writers? Send their queries — now part of the same old slush pile — to the recycling bin because the agents, the professionals, have no idea of what the next big thing will be? Oh, well, this is another development that shows which way the wind is blowing. Thanks for bringing it to our attention, Henry.

The way I interpret this article is that **only writers who have been traditionally published in at some point in their lives** can now pay agents to help them self-publish. So … why would any writer in his/her mind do this? It’s not that difficult to self-publish one’s own backlist, is it? Assuming a writer who’s been traditionally published but got dropped for one reason or another still has a following, this should be a no-brainer unless he/she is completely technologically illiterate. (Hmm …)

Writers who’ve never been represented by an agent or traditionally published shouldn’t get up in arms about this issue, really; it doesn’t affect us. While I can’t speak to how ethical this practice is (sounds dodgy to me), this sort of indicates to me that new writers who are married to the idea of taking the traditional route (querying, pitching) are pretty much SOL. Forget the “next big thing.” There won’t be one.

P.S. A lot of traditionally published books did not sell well for a reason.

Good points, Lisa.