For information and to request a copy of the novel this piece refers to, absolutely Free-Of-Charge, please visit

www.ktapproximate.blogspot.com

It has long been my belief that any and every opinion that can be held about a novel will be—that there is an artificiality in an author desiring to know whether their novel is “liked” or “disliked.” In my heart, there has always been a desire to converse about my work, to know someone’s “thoughts” on it, their “opinion” being an attaché, unavoidably there, but not of grave relevance. When I converse with friends or colleagues about some novel, it begins with an opening salvo, often knowingly hyperbolic in one direction or another, such as “This novel by Duncan McLean was brilliant” or “I don’t understand why anyone even reads Rupert Thomson” and only after this is out of the way does commentary of any value come along—commentary more to do with Literature as it is viewed by those speaking than with the content of the work prompting the dialogue. I have never been steered toward or away from anything I had a mind to read based on the “opinion” of another, but have been deeply affected—more often toward than away—by what someone “thinks” about some work, whether these thoughts are accurate to the ethereal “purpose and meaning of the author,” something irrelevant to me. Novels are dialogues waiting to happen, interchange: a novel not discussed, probed, touched, riffed on, is a dead thing, no matter the opinion of whomever.

It has long been my belief that any and every opinion that can be held about a novel will be—that there is an artificiality in an author desiring to know whether their novel is “liked” or “disliked.” In my heart, there has always been a desire to converse about my work, to know someone’s “thoughts” on it, their “opinion” being an attaché, unavoidably there, but not of grave relevance. When I converse with friends or colleagues about some novel, it begins with an opening salvo, often knowingly hyperbolic in one direction or another, such as “This novel by Duncan McLean was brilliant” or “I don’t understand why anyone even reads Rupert Thomson” and only after this is out of the way does commentary of any value come along—commentary more to do with Literature as it is viewed by those speaking than with the content of the work prompting the dialogue. I have never been steered toward or away from anything I had a mind to read based on the “opinion” of another, but have been deeply affected—more often toward than away—by what someone “thinks” about some work, whether these thoughts are accurate to the ethereal “purpose and meaning of the author,” something irrelevant to me. Novels are dialogues waiting to happen, interchange: a novel not discussed, probed, touched, riffed on, is a dead thing, no matter the opinion of whomever.

I want my novel to be a living thing, to travel, be thumbed and regarded, thumbed and ignored. The method I devised to accomplish this was to give it away. But, not just to give it away, willy-nilly, as this would accomplish nothing but having it perhaps read, perhaps not, likely winding up on some bookshelf or the floor of the back seat of a car. I wanted to give it away to a purpose, track it, give it to someone who would give it to someone else, too. Most important, I wanted to know what people “thought” about it—like it or not—and to converse with them, know the individual minds behind the thoughts.

It is well and good to hear some bit of praise—but praise from whom? It is often disheartening to hear work talked down on—but who is talking down? Either way, what else do these individuals have to say: about the novel, literature, music, film, architecture, anything? What germ is it that lead them through the novel? Who, exactly, did my work infect, one way or the other? I want to know: not to reverse a negative opinion or bask longer in the warm of a positive, but to actually have a conscious, individual, active audience.

Audience is something to cherish, to build, to keep. Whether the audience is comprised of “fans”, “detractors”, or people-who-just-like-to-read, opinionless, it is Audience that I have always sought for my work. But anonymity, on the part of Artist or Audience, is something I do not feel the need for.

To this end, my novel sent a calling card: ‘You may have a free copy of me, if you write a few remarks about what you thought of me, then hand me along to someone else, asking them to do the same’. My novel introduced itself, gave some context, a preview, politely saying ‘If this isn’t your thing, it isn’t–fair is fair. If it is, I will show up in your mailbox inside of a week’.

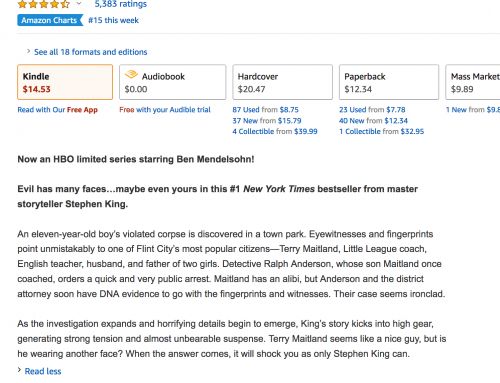

This cost me next to nothing—cost me less than the least expensive methods of advertising the novel I’d come across, methods hoping to flush out “paying customers”, to coax not only interest in the work, but interest in the transaction. It is not that I would ever put down on an author interested in promotion involving sales and I certainly would never devalue a work on such basis, but for myself Literature—certainly independent literature—has to be about the work, the transaction something cumbersome, better to jettison before it taxes one too dearly. For me, it could be said, the novel is the advertisement for the novel, readers are the profit, a currency far more valuable than three, four dollars in royalties, fought for tooth-and-nail, dribbling in now and then.

The way I see it, if it costs me six dollars to print and ship a novel to an actively interested reader and I get even a three remark back-and-forth correspondence, I have more than “evened out”. If each copy is read and remarked on by two people, I have profited immensely. Even if every reader just garners me another request, for which I pay for another book and shipping, I feel I am earning as I go.

It has never been and never will be the norm that a novelist will make a living for writing anything they feel like, has never been the norm that a novelist will make a living without getting a day job to do so. But, sadly, it is becoming the norm that a novelist who writes whatever he or she wants then becomes a scavenger, drooping over for pennies and crusts of recognition, losing, in my way of looking at it, the purpose behind literature: expression, connection, and, most importantly, open, unfiltered dialogue.

I have come across many brilliant writers, many sharp minded readers, and it seems repulsive to me to consider “paying out” a few dollars to know them—their insights, their individual perceptions of my words—a loss.

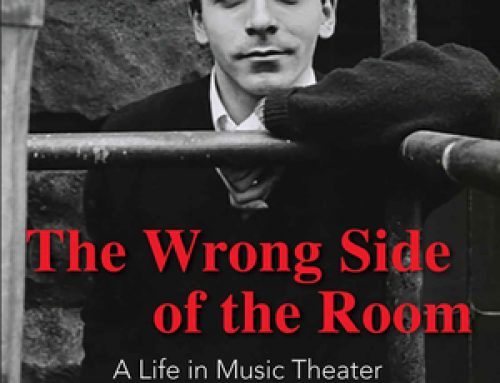

So Kaspar Trualhaine, approximate is free. Inside of one month, it has traveled to some four dozen people in the United States and has been received in Croatia, in France, England, The Netherlands, Australia. The books go out immediately, arriving in a week. And every time my bank account deducts six dollars and change (slightly more for France, I admit) I smile, leaning back, full, sated as though from the finest meal a restaurant ever served me.

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Leave A Comment