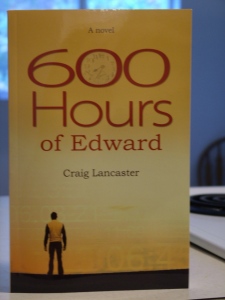

This interview with Craig Lancaster, author of 600 Hours of Edward, was originally posted on the blog of Jim Thomsen – “An Aspiring Author’s Journey to the Promised Land of Publication … Where Nothing is Promised.”

Edward Stanton is a man hurtling headlong toward middle age. His mental illness has led him to be sequestered in his small house in a small city, where he keeps his distance from the outside world and the parents from whom he is largely estranged. For the most part, Edward sticks to things he can count on…and things he can count. But over the course of 25 days (or 600 hours, as Edward prefers to look at it) several events puncture the walls Edward has built around himself. In the end, he faces a choice: Open his life to experience and deal with the joys and heartaches that come with it, or remain behind his closed door, a solitary soul.

— The back-cover copy for 600 Hours Of Edward, by Craig Lancaster

Last year at about this time, my good friend Craig Lancaster and I started the National Novel Writing Month event together. We checked in on each other every day, held each other accountable, talked one another through our struggles, kept each other excited about writing.

Only I blew it, getting bogged down by a bad start in mid-month, deciding to start over, and coming up short of the 50,000-word finish line by Nov. 30.

That’s right, folks … from nothing at NaNoWriMo time to mainstream publishing success in a year. I couldn’t be more proud of my pal.

As such, I think there’s a lot that all of us who have struggled to finish a novel — let alone get one published — could learn from Craig’s story. So, below is a Q&A I’ve done with him that may answer a lot of questions you may have about how he did it — and how you can do it.

Thanks, Craig. (By the way, if you haven’t already, follow him on Facebook here and on his fan page here.)

Q: I know you well enough to know that YOU are not Edward Stanton, the protagonist of 600 Hours Of Edward — even though you’re both fans of Dragnet, the Dallas Cowboys and rocker Matthew Sweet. So where did he come from? Was it from anything in your own experience?

A: That’s funny, because one of my family members, upon reading the book, said, “That’s you!” You’re right, of course. He’s not me. But I think, were Edward real, he and I could connect on a very narrow range of subjects we’re both interested in.

Edward’s creation stems from the chestnut about writing what you know. The things he likes are things I like, but those are only background pieces to flavor the story. His personality, his mannerisms, his heart — the things that ultimately make the story what it is — are his alone. He’s more afflicted, less bombastic, more regimented and far sweeter than I could ever be. I once described my method of creating characters like this: I steal attributes from people I know, and then I give them a good, hard twist into something else entirely. That’s what happened with Edward.

Q: 600 Hours Of Edward was written largely during NaNoWriMo in 2008. How much did the unique discipline of the event — the challenge to pound out at least 50,000 words in 30 days — fit with your personal work ethic?

A: I like to get to it, and NaNoWriMo certainly demands that. But I’d tried the event before and never made it very far, so I had more going for me than discipline. Actually, in a big sense, I credit you for what happened in those 24 days (that’s right — I finished the nearly 80,000 words of 600 Hours a week before the event ended). I was going to sit out NaNoWriMo 2008. I’d had a rough year, and I was just starting to emerge whole from a motorcycle accident I’d had in July of that year. To be perfectly honest, I didn’t want any more disappointment, and up to that point NaNoWriMo had been nothing but disappointing. But when you asked if I’d take part, I thought about it and figured I’d give it a whirl. I spent a day thinking up the broad outlines of Edward’s story, and on Nov. 1 I got to work.

Once I hit about 20,000 words, I knew I had something, but I was writing so quickly that I wasn’t sure how good it would ultimately be. I’m a pretty fast writer under any circumstance, but this was a marathon at sprint speed. These days, I still write every day, but I’ve learned to walk away when the wheels go a little wobbly. Whether it’s 400, 750 or 2,000 words that I’ve managed to get down, I know I’ve pushed down the road. Eventually, they all add up to a novel, if you keep going.

Q: Given your knock-it-out-of-the-park success with NaNoWriMo on your first go, what advice would you offer others who seem to struggle with the challenge?

A: NaNoWriMo 2008 wasn’t my first go; I’d attempted it at least twice previously. But it was the first time I’d put my ass in the chair and made myself write. The primary reason I was able to do so was I had a plan (read: outline) and a pretty clear idea of where I wanted to go. Those things help. Beyond that, I would tell anyone taking part in the event to really take the spirit of it to heart. The goal is to write 50,000 words, not 50,000 pristine, ready-to-be-published words. Allow yourself to write with abandon and with a minimum of cogitation. Accept the high probability that you’ll squeeze out some dreck. Form a symbiotic relationship with your story and write the living daylights out of it. If, at the end of 30 days, you have a good pile of clay to work with, you can worry about the finer points in December and beyond, as you hone it into something more approximating art.

In other words, don’t even worry about publication. Not yet.

Q: One of the more remarkable things about 600 Hours Of Edward, to me, is that you steer well clear of what I think of as “Debut Novelist Disease.” You don’t drown your characters and themes in dense poetic prose — in fact, you seem to have an excellent feel for what to leave out so that the story zips along and develops its characters and themes along the way. How did you manage to steer clear of the need almost every other first-timer has to describe the leaves on the trees and the dew on the grass and give every character a zillion pages of backstory?

A: My answers to these questions notwithstanding, I’ve always been a fairly spare writer. Part of that comes from my grounding in journalism and its demand that you draw the shortest line from A to B. Part of it stems from emulating writers I’ve admired, particularly Hemingway. When I was in high school, I mainlined Hemingway’s stories. At his very best, he wrote the most muscular, uncluttered prose imaginable. I think it’s a real shame that his style has fallen out of favor in popular literature, because to me, it’s timeless.

Here’s the other thing: Every time you flash back, or describe a room in punishing detail or whatever, the forward motion of a story stops, and so does that pleasant feeling of being swept along for the reader. You have to be able to judge when it’s OK — nay, when it’s vital — to stop the story like that. In all other instances, resist the urge.

One of the most enjoyable aspects of writing, to me, is letting the reader have some control over what a scene/person/object looks like. In 600 Hours, Edward spends a bit of time in his basement, building a toy for Kyle, the neighbor boy who is the first person to start breaking through Edward’s wall. I didn’t describe the basement at all. I figured that single word — “basement” — was evocative enough for anybody reading the story. He or she can decide whether it smells dank, or it’s finished, or where the work bench is, or how steep the stairs are. It’s out of my hands.

Q: Speaking of publication, how would you describe that feeling when you first held a bound, finished book, written by you, in your hands?

A: Everybody says it’s surreal, and everybody is right. You can’t help but think of what it took to get there and the high hopes you have for it.

That said, the biggest emotional payoff for having written a book is not rooted in the physical book living on someone’s shelf but in the story living in the mind of someone who’s read it and enjoyed it.

A: I would call it a mixed bag of success. I did so many things wrong, but I also did the biggest thing right: I wrote a good novel that captured the attention of a publisher who could do more for it than I could in terms of getting it out there. (The hard pushing of marketing and meeting readers and stumping for the book still fall largely to me, and that’s fine. Great, even.) In my haste to get the book into people’s hands, I emerged with a story that still needed editing and a cover that absolutely screamed “poor self-publish job.” Because the book was print on demand, I was slowly able to make good on those things, but it was a less-than-professional way to go about it, and one that still embarrasses me.

Q: What do you know now about self-publishing that you would have liked to have applied to that experience?

A: I would have been much more deliberate — securing a good editor and a good cover designer before the book ever saw the light of day. I would test-driven parts of it with public readings. I would have realized the value in a slower build, in getting blurbs and sending out review copies well in advance of the release. Slapped-together projects (very) occasionally work in publishing, but the smart money is on steady and professional. Self-publishers, more than anybody else, need to go with the smart money.

Q: Based on your experience, for whom can self-publishing work?

A: Despite some notable success stories — like my friend Carol Buchanan, who won a Spur Award for her self-published debut, God’s Thunderbolt — it’s undeniably a tough road for fiction writers. The audiences are harder to find and identify — this is also true for traditional publishers — and the legwork, beyond the marketing expected of almost any writer, tends to get in the way of the next book.

Peter Bowerman, the author of The Well-Fed Self-Publisher, contends that someone with a surefire nonfiction book and an established platform can realize some impressive pure profit by self-publishing. He seems to be proof of that contention. So I think, in a general sense, that nonfiction will fare better in that realm. Of course, nonfiction also fares better in the traditional realm.

I’m interested to see what the massive tectonic shifts in the industry hold for self-publishers. It seems obvious to me that the playing field is leveling a bit.

Q: Does having your book picked up by a publisher make you feel more “legit”? Or does your literary self-esteem come from other places?

A: I’m going to say yes, but in a very narrow sense. My publisher, Riverbend Publishing, has a reach into my market that I couldn’t replicate on my own, and if that reach means that more people will now read my book, that’s a good thing for my so-called legitimacy as an author. But the story was just as good when the book was a print-on-demand item that I moved one at a time.

As far as literary self-esteem goes, that comes strictly from readers. They’re the completion of the circle. The publishing apparatus is the necessary middleman between me and them.

Q: How has your newspaper background helped you as a novelist? Has it detracted in any way?

A: There is no writer’s block in journalism. You write, no matter what. So the biggest help has come from that. I have the discipline to sit down and do it, and if you sit down and write enough times, you’re going to reach the finish line (unless you’re Michael Douglas’ character in Wonder Boys). Journalism also helped me develop a sense for recognizing a good story — not just “news,” but also subtle human stories that really form the backbone of what I try to do as a novelist. I’m grateful for the ability to pluck those moments of inspiration out of the air.

Beyond the physical act of pounding the keyboard, newspaper writing and fiction writing are entirely different things. When I edit a news story, I want the salient details up top, because I’m banking on the fact that a good number of readers will never make it to the end. (Hmmm. Maybe I’ve identified what makes so many newspaper stories so relentlessly pedestrian.) With fiction, you assume that readers will reach the denouement and structure the story accordingly.

Q: You’re a very fast worker. Are you a writer who generally trusts his first instincts and find that they hold up through the revision process? How do you keep from paralyzing yourself over word choices, prose cadence, segues, plot points and the like?

A: My first instincts get plenty of challenges, but that happens in subsequent drafts. On the first go, I just try to get it down, baby. If you’re in perpetual first-draft mode, agonizing over every little thing, the finish line will never come into view.

I’m enormously hard on my work in the second draft. Things get bloody. The third draft may bring a smaller amount of corrective surgery. After that, I apply spit and polish.

I’ll say this: I’m thankful that it isn’t more of an ordeal. I know writers who put down 150,000 words in a first draft and spend subsequent drafts cutting that in half. That would drive me crazy. Or crazier.

Q: Writing for a small publishing outfit, you’re largely responsible for promoting your work and getting it into the hands of paying readers. What, in your view, are some of the best high-upside, low-cost ways of making that happen?

A: This is one of them. You have a lot of readers, and you’ve given me an opportunity to talk up my book. I’m involved in social networking about to my tolerance point — because I love it on its merits, and because it allows me to connect with readers and potential readers.

But here where I live, nothing beats shoe leather. I’m planning to support the bookstores that stock my novel, and I’ll go to any public library or civic group that will have me. And then I’ll hope that the math of word of mouth favors my book. We shall see.

Q: How confident do you feel in your public persona as an author? Do you feel comfortable giving readings, speaking to classes, gladhanding, talking with strangers, making friends among other authors?

A: I’m still a newbie at this, and I still have a vivid memory of my first public reading — the shakiness of my hands, the waver in my voice. But I got through it, and I’ve gotten progressively better at standing in front of a group of people and talking. Maybe I should join Toastmasters and really ramp up my game.

The thing that I struggle with, on a personal level, is that I’m fairly goofy, and I have to guard against that becoming too closely associated with my work, which is intended to be taken seriously. So in a public situation, I try to straddle that line between warm and amiable — which I am — and irrepressibly stupid. Which I also am.

Q: Who are some established authors you’ve gotten close to, and what have they been willing to do for you? What do you feel you can do for them … or do to honor in some way what they’ve done for you?

A: I’m lucky to live in a such a richly literary place as Montana. In my town alone, there are several established writers who have been very generous with their time and counsel, among them Sue Hart, Russell Rowland and T.L. Hines. Sue, who has forgotten more about the literature of the West than I’ll ever be able to learn, has invited me to her classroom and introduced me to other folks (and wrote a hell of a nice blurb for my book). I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to repay Russell for all he’s done. It was his encouragement, after he read 600 Hours, that convinced me I had something worthwhile. He’s given me opportunities I wouldn’t have had otherwise. And Tony has been a good friend to talk to about publishing and pop culture. We’re both kids of the ’70s and ’80s and we like a lot of the same stuff, and that makes our chatter free and easy.

Ron Franscell is another one, although not a Montanan. He’s been a vast resource for tips on staying sane and for some good, rollicking conversation.

I think the best thing I can do to honor them is to follow their example and be generous with my time and advice if I’m ever sought out in a similar way.

Q: 600 Hours Of Edward is set in Montana, and while its settings are largely urban and suburban, your reverence for the flavor and mythology of the West is obvious. What is it about Montana — and Billings, specifically — that speaks to you as an author as much as a person? Could 600 Hours Of Edward work just as well if it was set in, say, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania?

A: Billings is where I live and the place I know best, so it was an easy decision to drop Edward into this world. I’ve never been to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, but I suspect that Edward’s story could have been told there. You’d just have to change up some of the details; maybe Edward’s father would have a background in state government rather than in Big Oil.

In the stories I love best, setting is almost another character. Think of Of Mice and Men and that farm near the central California coast. Could Steinbeck have set it on a dude ranch in New Mexico? Maybe. But that changes the fabric of the story. Had he done that, we wouldn’t know what we were missing, of course, but imagining it retroactively takes something away from us.

Ultimately, I strive for a setting that provides a distinct flavor but a story that has universal themes.

Q: When you’re working, what’s a tolerable level of distraction? Music or no? Facebook or none? Dogs on your lap or no?

A: Absolute quiet and no external distractions. I’m lucky in that my most productive hours are after I get off work, between midnight and 3 a.m. My wife is in bed, the dogs are tucked away, and Facebook is more or less quiet. I sit in the dark and I try to find my way through the next scene, the next chapter, the next plot point.

Q: Do you ever have days where the words just won’t come? How do you deal with that?

A: If I’ve committed myself to writing on a given day, I really try not to leave without having pushed the plow down the field. I may know that I’ll never let the resulting pablum see the light of day, that I’ll double back and fix it at the first opportunity, but at least I will have done *something.*

As I write this, I’m in the middle of a lengthy break from fiction writing. In late July, I finished my second novel (now in the query stage), and I promised my wife that after writing two novels in less than a year, I’d let her see my face for a while. (And, to be honest, I needed the emotional recharge.) I’m about to start up again, and I’m eager to see how that goes.

Q: What expectations do you have for yourself in terms of eventually becoming a self-supporting, full-time writer?

A: It’s certainly my aim, though I’m heeding the advice of my friend Ron Franscell, who warns me that it’s a long road. Whether I ever get there, I’m going to keep writing and keep hoping that someone will find my stories worthy of publication. And, most important, that readers will find them worthy of their time and money. I don’t take either of those things for granted.

Q: What’s next for you? What can you say about Novel #2?

A: It’s finished. I’ve tentatively titled it Gone to Milford. Like 600 Hours, it delves into human relationships, but it comes with much darker undercurrents. 600 Hours is a very straight-ahead, sequential tale. Milford, I think, is the more difficult achievement. It spans a few decades and puts more things into play.

Here’s how I described it in query letters:

Mitch Quillen is in a rut. He’s on the cusp of his forties, his marriage is peeling apart, and his career has gone sideways. When his estranged father, Jim, calls unexpectedly — and then keeps calling — Mitch views the intrusion as one more problem he’s ill-equipped to handle.

Compelled by his wife to leave their home and go to his father, Mitch embarks on a journey not only forward in the here and now but also backward through a father-son relationship gone horribly wrong. Mitch goes to his father hoping to square accounts and find peace with what happened in the summer of 1979 in a small Western town, the place to which he traces a lifetime of losses. He finds reconciliation at home and with his father, and it comes with a harrowing yet affirming lesson in the power and the poison of the things we keep inside, and what happens when our secrets are dragged into the light.

Q: Any interest in doing genre fiction, or book-length nonfiction?

A: Genre fiction doesn’t hold a lot of appeal for me, at least not as a writer. I sometimes wish it did; if I could write two or three thrillers a year, my future in this business would probably be much more clear.

When I moved to Montana in 2006, it was partly with the idea that I would write a nonfiction book about my dad, who grew up here and whose young life was like something out of a Dickens novel. But then life and work took over, and I never made much progress on the intensive research such a project would require. As it is, I’ve managed to exorcise some of those compulsions through my fiction. It’s no accident that father-son relationships drive the narrative of both of my completed novels.

Q: What’s the nicest thing someone’s said to you about your writing?

A: A dear friend wrote to me some weeks back and told me that she works with someone who’s a lot like Edward — irrevocably fixated on details, difficult to know, obstinate and probably suffering from some of what ails my character (who’s OCD and has Asperger syndrome). She said that since reading my book, she has found herself caring more about him and being more patient with him. That brought tears to my eyes. I mean, imagine that: a fictional character inspiring more empathy in real people. And, brother, I can’t think of anything we need more than a greater understanding of each other.

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Thank you for sharing this story of persistence. Congratulations Craig! I agree with you on the importance of social media in your marketing and appreciate your understanding of the importance of these interviews.