Self-Publishing Review: When a self-published novel is awful, do you think the reviewer has any responsibility to spare the writer’s feelings?

Steven Reynolds: A writer will always be somewhat hurt by a negative review. You have to assume they’re reasonably happy with the book they published, otherwise why would they bother? So to have some stranger publicly detail its apparent failings is going to hurt.

When confronted with a book that doesn’t quite work – like Scott Cherney’s Red Asphalt – I try to do three things which I also do in manuscript assessments:

1. Explain what I think the author was trying to achieve, so they know if their intention was legible even if I thought the execution was lacking;

2. Explain why I think it doesn’t work, so the author has at least one considered opinion of what the novel’s core problem(s) might be; and

3. Foreground any good elements or signs of potential, so the author has something to work with.

It’s entirely possible to do those three things in sarcastic and humiliating language, or you can do them with a modicum of compassion. I choose the latter because that’s the way I’d prefer to get feedback about anything, and I assume other people are the same. Writing and publishing a novel is a serious creative undertaking by another human being, and that deserves some basic respect no matter what you think of the result. As John Lacombe recently said, the most important aspect for an author is the review’s tone. I’m also aware that my review might be one of only two or three a self-published novel ever gets. This doesn’t mean I apply lower standards. It just means I feel obliged to be more even-handed and to look at all aspects of the novel, rather than simply picking on the one thing that annoyed me the most.

Carol Buchanan: Yes, but not to the extent of writing a dishonest review. I think I’m responsible for letting readers know the quality of a book as I see it, and second, for giving writers an idea of how I think their writing might be improved.

“Quality,” that much over-used term, includes both the good and the bad. Aside from pointing out the book’s flaws, the reviewer should point out what the author did well. There’s always something to recommend a book.

It’s not easy for some writers to hear that a book they may have poured their souls into is not good, or has flaws. That hurts. I know. I had a bad review for my own novel, God’s Thunderbolt: The Vigilantes of Montana. I thought about why the reviewer didn’t like the book, and went on.

I assume when reviewing a book that it’s not the only book in that writer’s career. And while the writer may react as if that book is the best he or she can do, I don’t think so. We can always, always do better. If writers don’t let themselves quit, but consider what I and other reviewers may have written, the next book can be better. A career can grow.

SPR: Do you think reviewers should be paid for their reviews?

SR: Writing a review involves a good deal of effort, and that effort is valuable to other people. So, theoretically, yes, reviewers should be paid for that work.

Reviewers writing for newspapers are paid – much less than they used to be, of course, and there are fewer jobs. But they’re still paying ones. The business model of traditional media allows this. Newspapers earn money from selling advertising, and this requires content. Reviewers are content providers, and are paid by the publication. There is usually no connection between the publication running the review and the publisher/writer of the novel. Of course, it would be naïve to think media conglomerates with interests in both newspapers and publishing don’t run reviews of their own books – or that others aren’t influenced by publishers with deep pockets. But in most cases, there is no clear conflict of interest. The reviewer deals with an editor looking for good content, not necessarily “a good review”.

Self-publishing is a different proposition. Newspapers aren’t (yet) interested in running reviews of self-published novels. Websites that are interested, like SPR, usually aren’t monetized. So who would pay me to review for such a site? Only the book’s author. That seems to setup a conflict of interest: authors might have an expectation of receiving very favourable reviews; and reviewers who met that expectation might get more work from authors. So for money-grubbing reviewers there’s an apparent incentive to praise bad books. That’s the theory, anyway. This issue has been tossed about endlessly in self-publishing circles, and it always seems to land on the notion that author-paid reviews will be compromised and/or exploitative – or will be perceived to be so, which might be just as bad.

As I commented recently on another thread, I’m starting to think this “conflict of interest” notion is flawed. There is no incentive to write favorable paid reviews of bad books. You wouldn’t get away with it for long. Anyone reading your paid review can just as easily read the novel to test the veracity of your claims. The spotlight would be on you. So if you’re charging for reviews, there is actually a greater incentive to be honest and to work to declared professional standards. Everything in your paid reviews would need to be clear, well argued and justified with detailed examples. This could actually raise critical standards, not lower them. Successful reviewers trade on their reputation for impartiality and insight, and that would be quickly eroded if you were an obvious shill. So what’s the incentive to lie? You’d damage your reputation, and the reputation of self-publishing. And for what? The money you made until you got busted, I guess. A few hundred bucks at most. Wow, how exploitative.

Of course, the perception of corruption might still prevail, even if it’s a false one. But so what? Bowing to a perception strikes me as a strange path to follow here. Isn’t self-publishing advocacy founded on the notion that false perceptions can be changed? Aren’t sites like SPR dedicated to shattering the perception that self-publishing is a vanity ghetto of bad books that refuse to die? If we’re going to let our choices be driven by perceptions, we all might as well give up now.

CB: It would be nice, considering that we generally put in quite a bit of time into reading a book and reviewing it. After the initial reading, I’ll mull it over, sometimes for days, and then go back to it repeatedly to be sure of my reaction, especially if I find serious problems with it. By the time I click “Send” on a review, I have several hours into the writing alone. Fortunately, I’m a fast reader.

Conversely, paying a reviewer may bring problems, too. Salaried reviewers at some publications may be pressured to favor books from publishers with sizable advertising budgets. Or not to write a negative review of any book because the author or publisher might not advertise with that publication. From time to time, it has happened, but thankfully, not often. When someone’s job may be on the line, it would take a hard person to blame him or her if they chose to put principle behind feeding a family.

SPR: Aren’t reviews of self-published books simply another form of promotion?

SR: That’s never my purpose in reviewing a book, but most self-published authors certainly seem to see reviews in that way. They seek them out because they want to create a buzz or to build a readership, or because they want something to dangle in front of traditional publishers or agents. “See, I have all these readers who think my book’s magnificent! Interested now?” Despite all the posturing about “indie” spirit, a mainstream book deal is still the perfectly legitimate dream of many self-published authors. This is another reason I don’t mind the idea of authors paying for my time as a reviewer. They ultimately want to derive a financial benefit from my review – either a mainstream book deal or sales of the self-published edition – so why shouldn’t they invest a little money in trying to secure that?

It is questionable, though, just how valuable favourable reviews really are. They can help authors sell books online, no doubt. But no publisher is going to buy a book on the strength of reviews alone. They’re going to read the book themselves and make their own judgement. Same with agents. But good reviews could be one factor that helps them decide which books are worth considering.

CB: You might ask that about any book, self-published or traditionally published, but I have to say no. An author can use a good review for promotion, or learn from a bad review. The purpose of a review is not to puff the book, but to assess it, to analyze it for its strengths and weaknesses and to report on those to the reader and to the writer.

SPR: In your experience, what are the most common achievements and most common failings of self-published work?

SR: The near-universal failing of self-published work is the absence of editing. I find it immensely disappointing as a reader, not only because it’s annoying but also because it’s so unnecessary. The single biggest flaw in your work is the easiest one to fix! So why don’t you hire an editor to fix it? There are probably thousands of viable self-published novels out there that might have had a chance with a major publisher if the first ten pages were flawless.

For me, the singular achievement of self-publishing is that it provides an avenue for risk-taking. Authors who want to experiment with new styles, unpopular forms (like the novella), or confronting subject matter can leapfrog the gatekeepers and get their work out. Bonnie Kozek’s Threshold is a good example. It’s a terrific book, yet I can understand completely why mainstream publishers would shy away from it. It’s short, and way too weird and confronting for mainstream American tastes. Most publishers are too gutless to back weird-and-confronting. Until, of course, a weird-and-confronting book sells a million copies. Then they’re all into only weird-and-confronting for the next year.

I have to temper this praise with the observation that this achievement is far from common. Most self-published novels take no risks. Most appear to be sub-par attempts at mainstream fiction. I know it’s heresy to say this in self-publishing circles, but I believe the editors at mainstream publishers – the demonized gatekeepers – do a pretty good job in that regard, despite their conservatism. There is still a significant gap between the worst traditionally published novels I’ve read, and a lot of self-published fiction. The gap is narrowing, because the smart self-published authors have discovered the benefits of professional editing and good presentation, and they don’t mind investing a few hundred dollars to get these things right.

CB: The most common achievement is telling a good story. The most common failing is not telling it well. Notice I didn’t qualify the most common achievement, because simply telling a good story is not easy. From the most common failing, not telling it well, comes a host of other errors, or perhaps the errors add up to not telling the story well.

Add up. Notice that phrase: Add up. Quantity breeds quality. Like the Chinese water torture, an occasional typographical error, homonym, or grammatical mistake need not kill a book. Likewise, a flaw in characterization or plot construction or scene building might not ruin a story. But after awhile, when the errors have dripped long enough or often enough onto the reader’s consciousness, they may cause him or her to take the book back to the store. Or put it in the recycle bin. Or throw it across a room. Or worse yet, close it and forget it.

The broad categories of items writers should pay attention to are these:

- Mechanics: grammatical errors, typographical errors, homonyms, spelling errors, punctuation errors

- Plot construction: backstory, coincidence, illogical causation, deus ex machina*, conflict

- Characterization: motivation, psychology, physical realities, emotion, consistency

- Dialogue: speech patterns, dialect, carrying the story

- Point of view: clarity, logical changes, characters’ voices

- Setting: adequately described, suitable to the character

- Scene: reveals character, moves the story forward, forecasts events, builds conflict

- Description: adequate, lively, pictorial, effective

- Image and Metaphor: effective, building

- Writing (besides mechanics): sentence rhythm & variety, paragraph structure

Overall: These elements blend together into a story that engages the reader and keeps him reading.

Although there are no “rules” for writing fiction, there are best practices that time and again have proven to provide better reading experiences, i.e., to keep the reader in the novel’s fictional world, in the “fictive dream,” as one author calls it.

Consistently poor mechanics arise from not learning the tools of the trade, and can be prevented by studying writing or by hiring a good editor, or both. Problems in plot construction generally arise from not studying how good plots are constructed.

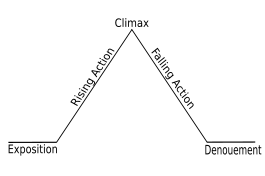

This illustration of Freytag’s Pyramid shows the general construction of plots in both novels and film. You can find more detail at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freytagspyramid.

Dialogue should carry the story forward as well as plot does, and good dialogue sounds individual to the character, but without using dialect. As I’ve said in a couple of reviews, I don’t think writing dialect is the best practice because the reader’s eye and brain stumble over unfamiliar spellings.

Another best practice in fiction writing is to keep to one point of view in a scene so as to avoid confusing the reader about whose thoughts he’s eavesdropping on. If a reader has to go back and figure out who’s speaking, acting, or thinking, he may stop reading. That’s not good for the writer and it’s not much fun for the reader, either.

The best writers not only know and understand English grammar, but love and respect our common language as well. These writers have an ear for the music of English, the elements that poetry teachers break out with terms such as alliteration, dissonance, assonance, and onomatopoeia. (Yes, I had to check the spelling. Doesn’t everyone?) All these combine to form the music of English, its sounds and rhythms, which help carry the story even though they may be considered “poetic values.” Besides these are similes and metaphors, which can add to the novel or detract from it.

Of course, if these values call attention to themselves instead of subliminally (as it were) increasing the reader’s enjoyment of the story, they also pull the reader out of the story. In that case, they become detriments to the novel.

SPR: Does a self-published book need to be free of grammatical errors to be considered for a good review?

SR: It’s a matter of degree. If an otherwise excellent novel has a few typos, or one consistent error that demonstrates a misunderstanding of formatting requirements (as Winter Games does), then I couldn’t condemn it. Sadly, the more common case is a book littered with errors of every kind: spelling, grammar, formatting … the works. It actually makes you wonder if the author has ever read a book.

I’m quite serious when I say that. The people who are best at spelling, grammar and layout are big readers. Spelling is 90% recognition, not recall: the word just “looks right”, and that only comes from a lot of reading. The same applies to grammar and layout. So broad sloppiness tells me the author has no real interest in reading. Why does such a person want to write a book? Because they want to be famous? Because it would be cool to see their name on the cover? Those aren’t good reasons to sit down at the keyboard, and even worse reasons for others to waste their time reading the result.

CB: Yes. At the very least a carpenter should know how to drive a straight nail. Grammar, spelling, and punctuation are part of the tools of our trade and we damn well ought to know them. Standards for self-published novels should be no different from those of traditionally published novels.

However, the grammar has to be appropriate to the characters, and sometimes the narrator is a character, too. If the narrator is big into rap, he might narrate the book in that form of English. I’d have difficulty reading it unless the writer is careful, or perhaps I’m not part of that author’s target audience. I’d recommend considering the audience, then writing for it. Don’t misunderstand me. I don’t mean dumbing down anything just to get more readers.

Being able to write in a different form of English implies that the writer can write good standard English in the first place. It’s entirely one thing to write grammatical errors because the character doesn’t know better (Martha McDowell in my own God’s Thunderbolt, for example) and another thing completely to write ungrammatically out of sheer ignorance. The first contributes to characterization; the second cheats the reader.

SPR: Should a reviewer always include positive aspects of a book even if it is deeply flawed?

SR: For sure, but only if the book actually has positive aspects. Some books don’t have any. If I can’t find anything to praise within the first 100 pages, I refuse to review it. This isn’t because I want to spare the writer’s feelings, but because I want to spare myself the agony. Life’s too short to waste a week reading and writing about something that bad, when there are so many better self-published novels to read and review.

CB: Yes. I would hope that novelists – myself included – can learn from a negative review. In the bad review I mentioned earlier, the reviewer did not at all like the love story in it. He mislabeled the book a Romance, when in fact it is anything but. I had included the love element in to lighten the story, to mitigate the violence. However, his review prompted me to consider why he might have come to that conclusion and to think about the role of a love story in a novel about violent times. One of my test readers had not liked that sub-plot, either. I won’t be changing my approach in the next novel (now under way), as it turns out, but I have refined my definition of my audience.

To answer the question directly, if there are no positive aspects in a review, the writer is less apt to consider anything the reviewer says. Including only flaws in a review is as useless as including only a novel’s strengths. Eventually, neither readers nor writers come to consider that reviewer trustworthy . And you know what? They’d be right.

(*Deus ex machina, literally god out of a machine, comes from an ancient device that brought an actor portraying a god down from the clouds to resolve the plot. Modern equivalents include the cavalry or the police arriving just in time to save the protagonist. )

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

I don’t remember the falling action as being equal in length to the rising action. Should be a lot shorter.

You’re right, Kristen. I grabbed that one out of public domain much too quickly. In terms of percentages, the correct pyramid might have about 10% exposition, 60% – 70% rising action, 20% – 30% falling action, and 10% denouement (aka wrap-up). Of these percentages are not hard and fast, but that seems to be about the proportion. (Obviously, they’re not hard and fast because added together in one way, they’re 120%.)

Thanks for pointing it out.

Carol

Carol – I’m not even sure why I DID point it out. Ha! It’s not crucial, and it’s not really relevant to the conversation. I was just thinking, “Wait a minute!” and commented before thinking about whether it was actually worth a post.

One of those days. 🙂

Kristen, it’s cool. Really. No biggie.

Steve has made a good point about writers needing editors. I could not have lived without the editors in my former life as a technical writer for an aerospace company. They took my fairly raw material and not only formatted it into clear manuals with different levels of heads and subheads, an index and a TOC, they also questioned my usage, grammar, punctuation, spelling — and the facts. They’d question me, I’d go back to the system or to the engineer and double-, sometimes triple-check. Together, we did good work in an arena that demanded absolute accuracy.

But sometimes the editing isn’t so good, and I’m seeing some pretty awful editing in some of the books I’ve read in the last couple of months — not only in the self-published books, but in traditionally published ones, too.

Homonyms — words that sound alike but mean something completely different — are something that often escape the editorial eye in self-pubbed books, and I have taken to task more than one writer who didn’t seem to know the difference between write-right-rite, or cite-site-sight, or grizzly-grisly-gristly. Sea-see-si I haven’t seen yet, but I expect to. And yes, I’ve done it myself, in this very e-zine (site-cite). It’s the accumulation of homonyms that mounts up to critical mass in a book and lowers its quality. Just as with other errors.

But now I’m starting to notice poorer quality among books that are edited. So I wonder sometimes if writers depend too much on editors who don’t have the knowledge or the hyper-critical eye to support their knowledge.

Living in bear country as I do, one of my favorite errors is: “grizzly remains,” when the writer means “grisly remains.” Maybe it’s time to find a completely different phrase to describe rotted cadavers, because I’ve seen it four times in different books during the last 6 months.

If it occurs only once in an entire book, it’s a slip. If it occurs more than that, I suspect the writer and/or editor just doesn’t know and should take the time to learn the tools before issuing a book.

It doesn’t only happen in self-published books, though. Just 2 days ago I started a gritty mystery by a Scottish author, published by St. Martin’s press. In the first 10 pages someone discovers the aged corpse of a small child, and soon the detective is looking at — you guessed it — “grizzly remains.”

The moral? Writers should be aware that skill varies widely among editors. Ask for credentials, samples of work, references. You’re hiring them and your potential career depends on getting the best you can.

My favorite was an author I was editing saying something missed a guy by “a hare’s breath.” How cute is that? Totally spoiled the scene suspense with the whizzing bullets and stuff.

Another one I see all the time is “make sure to keep me apprised of the situation.”

It’s just the kind of thing where people hear it one way as a kid, and never see it written, so it doesn’t even occur to them to look it up when they’re writing. Which is reason #487B why it’s good, and not shameful, to have an editor.

(And by “apprised”, I of course mean “appraised”, because I’m showing it the wrong way. Sigh. That’ll be reason #487C.)

“Grisly remains” pulls me right out of the story. It’s such a cliche, I don’t even see anything in my mind when I read those words anymore. I can almost smell “rotted cadavers”, though, even if it is a little clinical.

Now I’m confused. “Appraise” means to assess the monetary value of something (a house) or the importance or nature of something (poetry) , while “apprise” means to send word or give information about the state of something (a situation or event).

I love the example of a “hare’s breath” instead of a “hair’s breadth.” When I read that something missed by a whisker, I wonder whose and did the writer mean length or width?

The same Scottish author later in the book had such a vivid description of a rotted cadaver that I had to stop eating my supper. A good way to go on a diet.

I don’t think I’ll ever see the phrase “grisly remains” again without laughing and thinking of nine-foot-tall bears. Poachers at work!

This question is for Ms. Buchanan:

in your continuing dialogue with Steve Reynolds, part 2, you state:

“Quality,” that much over-used term, includes both the good and the bad. Aside from pointing out the book’s flaws, the reviewer should point out what the author did well. There’s always something to recommend a book.”

I’m interested to know where you think you followed your own advice, in your review of Winter Games. In hindsight, on the off chance that you don’t think you did, I’m wondering what you’d add or change.

Thanks

“The story is original and the main character is engaging.”

What made the story original and the main character engaging?

You present as far too learned and compassionate an individual for me to believe, for one second, that your idea of “pointing out what an author did well,” and “something to recommend” merits one cursory sentence.

I have followed the dialogue between Mr. Reynolds and you with an “insider’s bias.” I know John Lacombe. although not well by any means. When I read the comments above, and particularly since Mr. Reynolds seems to mention John in his examples, I consider what you both have to say in the context of Winter Games. Whiile other reviewers may comment on theory or general philosophy, few if any, are coming to this with an insider’s knowledge of the book. When I read your comments, always in the back of my mind is that you both reviewed the same book. That’s what prompted this dialogue. His review was positive, yours was not. This intrigues me. That intrigue, for me, goes way beyond differences of opinion or intentional fallacy.

You say the book is not well written. Mr. Reynolds strongly suggests that it is. Or, impressive enough for a first attempt. Both of you have sufficient English skills background. The developing dialogue strand is wrapped around techniques of writing, right down to homonyms. Now, I know you value Mr. Reynolds expertise. I know he values yours. And I’m sure you both know that John has a writing degree from a prestigious university and had an agent and editors who perused Winter Games.

So, why do you disagree to the extent you do, about the quality of writing in Winter Games?

“Janet”, your last comment seems to me to be a veiled accusation that Carol Buchanan has some kind of personal bias against John Lacombe. You cannot accept that differences of opinion or interpretation alone could possibly account for the different conclusions we reached in our reviews. So what else could account for it, except some kind personal bias, right? What else is there?

I’m not interested in getting involved in this kind of nonsense, as “intriguing” as you may find it, but I will say this. Yours is a quite remarkable accusation considering that, of the three of us, you’re the only one who personally knows John. Have you considered, even for one moment, that personal bias might have influenced your reading of the novel?

Bias factors in and if you look above, I stated that. I said I have “insider’s bias.” Nonsense you say? Your dialogue has evolved to a serious discussion about writing, including mini-lessons of a sort. There are no veiled accusations here by me. And what’s with the quotation marks? My name is Janet Stevens and I am a special education teacher at Lebanon High School. I do know John Lacombe because he was a student here, ten years ago. What are you suggesting, that no one who has a connection to John can participate in a legitimate discussion? That only reviewers can voice their opinions and be taken seriously? I made no accusation whatsoever. It’s almost as if you want to believe I did, so that you can lump me into some kind of evil conspiracy of those defending John Lacombe.

Whether you want to believe it or not, I really do want to know how two very learned people can disagree so pointedly about the quality of writing in Winter Games. After all, that was at least part of the impetus for “this dialogue.” I think the book well written. Teachers at this school use the novel in their classes. Call this the science of writing if you want. I’m not talking about interpretation and I said that. I’m talking about the mechanics of writing. I’ll ask the question again.

Why do you disagree to the extent you do, about the QUALITY OF WRITING in Winter Games? If you don’t want to engage in a discussion about a question I think is extremely valid, that’s your choice.

Please let me explain further. When you both discuss the mechanics of writing, as you do above, I look at Ms. Buchanan’s comments and infer that when she makes suggestions of what writers need to do, she’s implying that John Lacombe did not do those particulars in Winter Games. Your review, however, suggests that the novel is well-written. There’s a diametric opposition about the writing itself. Not the interpretation, the writing itself. And since this disagreement gave Mr. Baum the idea for the dialogue strand, I thought it fair to further the discussion in this venue.

I just returned from a Saturday lunch, during which colleagues and I planned an upcoming unit on Winter Games. At least one of them has already assigned the reading of Mr. Reynolds’ and Ms. Buchanon’s reviews of the book, and we expect this could be a significant motivator for our students. As a SPED teacher, my role is one of advocacy for the disenfranchised students. John Lacombe’s visit to Lebanon High School last spring was a tremendous motivator. Kids who never read anything on their own are reading his book now.

We have a golden opportunity here. Blogging has just tied video games in popularity. I’m not sure what the self publishing review site gets out of increased traffic, but you might be getting a lot more, soon.. You have probably grown weary of the “robot” issue, but please remember that high school kids are seeing this for the first time. What we want them to do is to examine each review, and defend their own analysis. We want them to translate, synthesize and evaluate.

My question to Henry Baum is: Can high school students get involved in this dialogue, and revisit some of the previously expressed sentiments? I want my own students to be passionate and to query the reviewers with thoughtful preparation. I do not want them to be treated disrespectfully, however, for seeking answers from either Ms. Buchanan or Mr. Reynolds.

The local newspaper, The Valley News, did a lengthy piece on John, after Winter Games came out. John covered sports for the paper while he was in high school. It’s possible the paper may pursue a story about students’ response to Ms. Buchanan’s review. That depends on how fired up the kids get, how many there are, and what can be quoted in the paper.

So please let me know your thoughts. Perhaps, if funds allow, this could culminate in a panel discussion at the school involving Carol Buchanan, Steve Reynolds and John Lacombe.

Thanks.

In response to #14: Okay, Janet, for the sake of argument, let’s assume you’re serious. Let’s review what I actually said about the QUALITY OF WRITING in “Winter Games”:

“The writing style is clear and efficient, but Lacombe also understands the music of language. He knows how the rhythm of it can propel you across the page. Exposition is kept to a minimum. Where it is eventually required, it’s mostly delivered through dialogue and in scenes that also advance the action, so Lacombe has clearly thought about how to deploy it. Some of these scenes are long and the exposition a little too wordy, but they often segue into action-packed flashbacks which ‘show’ more than they ‘tell’, which is satisfying. It’s mercifully free of the awkward phrasing and endless typos that plague so many self-published novels. My virtual editor’s pencil was hovering, but was rarely put to use. There’s the odd overuse of adjectives, but on the whole this is the clean, workmanlike language you expect in an action-thriller and it really is a pleasure to read.”

I don’t think it’s beautiful language. It’s not writing for the ages. It’s workmanlike and rhythmic. And I think that’s appropriate for an action-thriller. In my experience, readers of the genre expect the language to be almost transparent. It has a job to do; it’s not the raison d’etre of the novel. John’s writing does the job, and his training in journalism probably equipped him well for this. It ticks two boxes on the list of “good” qualities I mentioned in Reviewing the Reviewers Part I: an appealing voice; and a tone and style appropriate to the subject.

But John is, as I said in my review, an “emerging writer”. I’ve read better stuff in action-thrillers, and you probably have, too. I have a habit of noting down particularly powerful or technically effective passages from the novels I read. For about fifteen years, I’ve been adding them to an electronic notebook that now runs to over 40,000 words. I didn’t note a single line from “Winter Games”. This doesn’t make it “bad writing”; it just means the textual surface of the novel isn’t its strongest point. If you’d like to suggest a passage that does deserve high praise for its power or technical efficacy, let’s hear it.

In the comments on Carol’s review, I also pointed out a problem with the narrative viewpoint (another technical aspect on my list of “good book” qualities) and discussed its impact on emotional engagement (Comment #9). I hadn’t been able to put my finger on the problem when I read the novel back in April, but Carol’s review made me realize what it was.

As for Carol’s thoughts on all this, and why she might take a different view, she’s perfectly capable of speaking for herself, if she’s inclined to do so. Although I will say this, which I also said in Part I: Carol is a novelist, I’m not. As a novelist, she would spend a lot of time messing about with words on the page trying to get just the right effect, and she is clearly a deep thinker on the subject. She brings an insider’s perspective to the technical work of writing that I could never bring, so her opinion will carry some weight.

Yes, her opinion. Contrary to what you seem to think, Janet, reviewing is a matter of opinion. Subjectivity counts for a lot, even when looking at what you call the “quality of the writing”. I could give you two sentences that are both technically correct in terms of their spelling, punctuation and grammar, and which both attempt to describe the same thing. One could move you to tears, the other might fall flat. This is because, as I said in Part I, “…the act of reading – making meaning out of words on a page – is an essentially subjective experience. They’re just dots of ink assembled into shapes we call letters and words. The magic happens in our minds, and it’s going to be influenced by what’s already there.”

This whole dialogue has been about exploring that subjectivity.

In response to #15: I live in Australia, Janet, so I won’t be flying to New Hampshire for any panel discussion. But I’d be happy to answer questions from the kids via e-mail or on a blog, or respond to questions from the local newspaper.

By all means, have your students become involved. If this site can be a catalyst to get them interested in literary criticism and reading the book, then great. I’m sure Carol and Steven will be respectful if the students are respectful in turn.

Self-Publishing Review: When a self-published novel is awful, do you think the reviewer has any responsibility to spare the writer’s feelings?

“Responsibility”? No. Common courtesy? Yes. A review which does nothing but criticize and ridicule tells as much about the (unforgiving; unpleasant) reviewer as it does the book.

SPR: Does a self-published book need to be free of grammatical errors to be considered for a good review?

Mainly yes. You would expect a book off the shelves of a local bookstore to be 100% free of grammatical, spelling and punctuation errors. In general, SP books are intended for the same audience, so they should be of the same standard. OK, in practice SP authors don’t have editors and proof-readers to help them out so a handful of errors might creep through. But I think any reader or reviewer of an SP book knows that, and will make a (small) allowance.

SPR: Should a reviewer always include positive aspects of a book even if it is deeply flawed?

Yes, of course, if there are any. A reviewer acts as a sort of filter for interested parties – the reviewer didn’t write the book. He or she can only report on what’s there. If there are no redeeming features, then the reviewer must faithfully report that there are no redeeming features. But I’ve been reviewing short stories and scripts on and off for years, and I can only remember ever reading one story that had no positive features whatsoever.

People often disagree on whether a book is well done or not. Some people think literary fiction is the only kind worth reading. Other people dislike anything that is not written in their favorite genre. Still others consider literary fiction to be dull, depressing, and not worth the tree that was cut down to make the paper. They are entitled to their own opinion.

Steve and I come at this from two different perspectives, as he says. I’m a novelist as well as a reader. An odd thing happens when someone, people, like me for instance, changes over from reader to novelist-as-reader. Like a lot of writers, I’ve lost the ability to read purely for pleasure. I read all novels critically, not simply for enjoyment. I’m always alert for the poorly cast sentence, the major and minor errors in usage, the misused idiom, the poorly placed modifier, the flat characterization, the illogical plot step. All the problems I’ve listed above. At times I’ll find writing that moves like clotting blood because it’s so dependent on prepositional phrases to carry the meaning rather than on the kernel. (The kernel of meaning is the Subject and Verb together with the Object, Object Complement, Complement, and all their variations. It does not contain modifiers.) Some novels I absolutely love, but my critical mind has to admit that they might not be very good books. If I were to review a book that’s not so good but I like it anyway, I’d still be duty bound to state what its flaws are. I have hated some novels that won the Pulitzer Prize, and I think the Nobel Prize is politically motivated and not a reliable judge of good literature. However, I could be wrong. The Nobel judges look at literature worldwide, and admittedly my knothole is much smaller. I thought the female characters in Lonesome Done were flat, but it got the Pulitzer and has much to recommend it.

My liking a novel does not mean I think it’s necessarily the best book ever, still less that it has no flaws. I like some books because the characters are interesting as well as sympathetic, because the story takes me into the world of that novel, because the writing sings, or because the setting is fascinating. Or all of the above. I thoroughly enjoy Robert B Parker’s minimalist style and I love James Lee Burke’s stylistic opulence. Reading the two of them at the same time is great fun and somewhat mind-bending because they’re so different. In terms of truly great books, the novels of E L Doctorow stand first for me, although most of them are not especially accessible. My all-time favorite of his is The March, but his latest, Homer & Langley, while gorgeously written, won’t be ending up on my shelf. The first paragraph contains a sentence so long and beautiful that only a master of the English language could have written it with the control he demonstrates, but the novel is about two handicapped brothers’ slow decline toward death. Not for me. I prefer stories that are more upbeat.

When I review a book, I read it in context of all the English and American literature that I’ve read in more than 60 years, coupled with (as I mentioned before) a PhD in English Lit. I also read with a mission regarding self-published fiction in general.

I hope every time I open a self-published novel to find a book that can help dispel the prejudice against self-published novels. So far, out of 20 (by other writers as well as those sent me for review) I’ve found only one: Craig Lancaster’s 600 Hours of a Life, soon to be released by a traditional publisher as 600 Hours of Edward. Another book comes very close, while a third needs more work to overcome what I consider a serious flaw. In due course Henry will post my reviews of both of these and more.

A self-published book will be judged against everything else they’ve read by people looking for a good read. I’ve watched people in bookstores. They look at the title, then the front cover, then read the back cover, then open the book and read the first paragraph, maybe a page or two. Every step of that is a judgment call that leads up to the final question: buy or not buy? All the time they’re weighing the book against what else they like to read. Occasionally, a self-published book is picked up by the stores and has to meet those same readers’ standards. It has to compete with all the other books in the store for the readers’ limited discretionary spending.

I review books, then, from the perspective of someone familiar with English-language literature, with what it takes to write an award-winning novel, and with the perspective of a reader in a bookstore.

If people think I’m tough. they should hang out at their local Borders or Barnes & Noble, grab a coffee, and watch people decide what to buy to read. They are the truly ruthless ones, and all of us writers should be aware of that. I’ve watched people do that with my own novel. It’s not easy, but it was a good reminder. The ultimate critics are the readers. They’re the ones who judge all of us writers.

Re: #15:

I would be happy to respond to comments regarding reviewing, literary criticism, or standards in fiction generally, but I’ve said everything I have to say about Winter Games, a subject which seems exhausted by now. So far as traveling to New Hampshire is concerned, that’s not possible. I have commitments stretching beyond the next year. I’m committed to releasing the next novel in a year, a third the year after that, and I’m negotiating with a potential publisher to deliver the fourth book in 2012.

Outrageous oversight on my part! When I named the best self-published book I’d come across, I forgot to mention two others, which I reviewed for different online sites. One is The Shenandoah Spy by Francis Hamit, who has since become an online friend, and The Gathering, the first book in Celia Hayes’s Adelsverein Trilogy.

Unlike Craig Lancaster’s 600 Hours of a Life (the self-published version of 600 Hours of Edward), The Shenandoah Spy and The Gathering are historical fiction. Both are well researched and well written, and the characters are sympathetic and well drawn, and like people I could liked them a lot. Both could have been picked up by traditional presses, but as one agent informed me when he rejected my novel, “period pieces aren’t selling.”

Three good — self-published — books. Worth anyone’s time and money.

“Period pieces aren’t selling.”

Tell that to Hilary Mantel who won the Booker Prize.