What’s also problematic is that writers may take this one step further and consider that their writing is indeed better because it has been accepted by an editor. I don’t want to limit the idea that getting accepted by an editor and receiving a paycheck is enormously validating. Of course it is. I’ve been traditionally published as well with Soft Skull Press in the U.S., Canongate in the U.K., and Hachette Litteratures in France. I come to self-publishing with a sense of both sides of the aisle.

But just because a book has been accepted by an editor does not mean it is automatically better – and dispelling this idea could help self-published books gain more clout, and reduce the amount of prejudice.

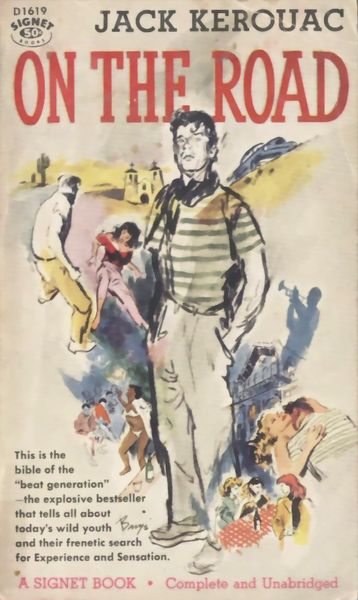

Let’s look at a writer like Jack Kerouac. Most people think of Kerouac as a fifties writer. Actually, Kerouac was going on the road in the late forties, after the war. On the Road was written in 1951 – but it was not published until 1957, towards the end of the decade. Jack Kerouac did most of the writing that’s part of his legacy before On the Road was ever published. Is On the Road a better book in 1957 than it was when it was initially written in 1951? I think most people would say no: publication doesn’t determine worth. The book is the book.

Take other writers like Herman Melville and F. Scott Fitzgerald. They both died unheralded and Moby Dick and Gatsby become a part of the literary canon only posthumously. The same goes with a writer like Philip K. Dick. Read to some degree while he was alive, but not nearly as regarded as he is today, with editions being put out by the Library of America. Crime writer Jim Thompson is another one, who had a renaissance in the nineties.

Obviously, not all self-publishers are geniuses like the writers mentioned above. They don’t have to be. This is just to point out that a book’s success or lack of success does not determine if a book is worthwhile. It can take decades for a writer to be discovered and reexamined.

Literary Longevity

One of the major problems in the publishing industry is the fact that they gauge writers one book at a time – if one book doesn’t sell, writers are boxed out. But really, this isn’t how writing – or any art – unfolds. Someone said that writers generally write the same book over and over again in different ways. Not to say those books can’t be unique, but personally I feel like I’m writing one long novel made up of smaller novels. Each novel builds on the last.

So writers should be gauged on what they’ve accomplished during their entire careers, not based on one or two books. Supposing a writer self-published five novels, and then the sixth novel gets picked up by a traditional publisher, who then puts out traditionally published editions of the first five books – which are all successful. Are those five self-published books now better than they were before? No, because that would be like saying that book sales equals artistic worth. It doesn’t – it’s just that the books are more accessible now that they’re distributed traditionally.

There is some proof in consensus. But Dan Brown sells more books than, say, Michael Chabon. Is Dan Brown a better writer? “Better” is subjective, not based on sales figures.

This idea that editorial acceptance means that a book is more worthwhile just needs to go away. Books have worth regardless of an editor’s stamp of approval – even the number of readers. That’s just an example of how much money has changed hands. To claim that is proof of a book’s worth is a seriously corrupt model of how art should be valued.

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

This is an excellent article. It’s true: the literary value of one book over another is entirely subjective. And even when there’s something approaching a consensus — when you encounter many people agreeing about the worth of an author — that consensus is subject to change over time. Today, the consensus would rank Dickinson over Longfellow — but that rank was reversed a century ago.

And I think all writers — even those who put down self-published authors — recognize that this is true. After all, if there were such a thing as objective literary value, and if agents and publishers made their decisions based on that objective determination, then there wouldn’t be any point in sending a manuscript off to more than one agent or publisher. If literary value were objective, then that first rejection that you would receive would be enough to convince you that your manuscript ought to be thrown in the trash. But the fact that writers send manuscripts and queries to dozens of agents and publishers is at least an implicit recognition that judging the value of a piece of writing is always a subjective process.

You’re absolutely correct, and it’s perhaps even more clear in music, film, and visual art. Acceptance by the industry’s established gatekeepers has no relationship to quality, in either content or execution; as you say, it’s just about “how much money has changed hands.” We live in a celebrity culture that would have us believe that fame equals talent. But I’ve found that whether I want attention from the masses or not is meaningless, because I can only write what I can write. I express who I am, and it does not fit current trends, it falls way outside the zeitgeist, but it is what it is. I’ll be grateful for s small audience of discerning readers; there must be a few who share my sensibilities, and so I’ll count them among my friends. Making a living from my fiction is a fantasy that I can use for a moment’s entertainment, but I’m too old and realistic at this point to imagine my quiet little stories will set the world on fire. Still, if a few people beyond my freinds and family think they’re good, I’m happy. Maybe that’s literary value.

Since Roland Barthes proclaimed “the death of the author” and the emergence of the reader as the sole arbiter of meaning, “literary value” has been seen as an entirely subjective, not to mention deeply suspect, notion – in academic circles at least. No student of literary studies would attempt seriously to define it.

Back here in the real world, we assign literary value all the time – as individuals and as a culture. I love certain books; I can even come up with my own personal literary canon. So does the culture at large, and here in the English-speaking West that canon would include books as diverse as “The Da Vinci Code”, the Harry Potter series, “The Catcher In The Rye”, “To Kill a Mockingbird” and the Bible.

People assign literary value for all kinds of reasons: books they enjoyed; books that spoke to them about their own lives; books they read at school and remember fondly; books they feel morally obliged to say they enjoyed, even if they hated them. I’m sure millions of people could assign “literary value” to thousands of self-published novels if only they got the chance to read them. But they don’t. And they won’t get that chance until self-published books get taken seriously by bookstores (because, despite Amazon, physical bookstores are still where most people prefer to browse and buy) and taken seriously by mainstream reviewers in the mainstream media. And that won’t happen until a singular self-published novel comes along that is either so good or so word-of-mouth-popular that it forces the world’s attention en masse towards it, AND the author subsequently REFUSES to sign it over to a mainstream publisher.

I’m not sure that will ever happen, though. Most self-published authors crave the mainstream’s stamp of literary credibility – of literary value – as much as readers do, don’t they?

A well-executed self-published book (good design interior and exterior, good marketing, good writing, good story, good characters) can erase the perception that the book wasn’t vetted by a traditional publishing house. I still have people congratulating me on being published (and gushing over the book after reading it), which I accept, since it demonstrates that I’ve reached my goal of obscuring the fact that my book is self-published. There is still a stigma, and I wanted to leap it so readers would engage with the book.

Your statement really resonated with me: “This idea that editorial acceptance means that a book is more worthwhile just needs to go away.” Editorial acceptance is virtually meaningless for fiction as far as assessing its quality. The big publishing houses can assert that they improve the quality of the books they choose, and that their selection process is meaningful, but we’ll never know, will we? Do interventions from commercial agents and editors preserve and enhance a new voice’s interesting qualities or mainstream them out? There’s no transparency without self-publishing to show what can go on otherwise. Given the number and consistency of successful self-published books, I’m becoming convinced the editorial selection and editorial processing of commercial publishers probably weren’t all that helpful to many good writers.

In some fields — scholarly communication, for instance — peer-review and editorial processes are extremely important, because what is being pursued is an approximation of the truth, if not actual new immutable facts of physics, biology, or earth sciences. The reports of researchers need to be able to withstand a crucible of scrutiny and validated by experts. But for fiction, where it’s art and entertainment, why shut down a motivated author with a story to tell?

The “scarcity model” of marketing, printing, and distribution is going away. Mass media is fading. Niche media is emerging. The guardians of resources at old-guard publishing houses will have less and less to do as time goes by.

This I found yesterday on Bookforum from David Ulin — a great read and another take on Kerouac if anyone is interested.

http://www.bookforum.com/inprint/014_03/831

Great article, thanks for posting that. His cover for OTR is amazing – how is it I’ve never seen that, and how is that an edition was never released with that illustration? It’s amazing that Kerouac still needs to be trumped up as a legitimate writer, and not just a fad or a spokesperson, but an actual artist. A book like “Why Kerouac Matters” shouldn’t have to be written.

My comment/question does not have anything to do with literary value and self-publishing. I am convinced that a self-published work can have literary value.

I have another question, for someone to answer: Going the traditional route, is there ever a concern about recycling your work to multiple publishers(in the fact of rejections) that the ideas can be “stolen”(i.e. recast in just different words)? I realize that the likelihood of this is small. Still, an individual who has put in so much work can’t afford to take a chance. One possible value of self-publishing is that it is “submitted” once and accepted. Is the issue that I have brought up ever been referred to before, or is it even a realistic concern?

Thanks for your help.

Good question, but honestly I don’t know the rate of stories getting stolen so I’ll have to look into it. I imagine though that a virtually unread self-published book could get stolen as well, and the publisher could claim ignorance about the previous book – with even more cover because the book was never submitted.

I’d ask this question again in one of the forums because it’s likely that a lot of people won’t see this on an old post.

Thanks, Henry. Someone was telling me about the “poor man’s copyright”(mailing it to yourself). Once again, I think it unlikely that anyone would risk his/her reputation, but it doesn’t hurt to error on the side of caution.

I agree that it’s all subjective. Look at LORD OF THE RINGS. It has a cult following. You either love it, or hate it.

I’ve said before and stand by this statement: the ratio of good books and bad books in both forums (SP & TP) is 50/50. I even had a sales girl at Borders tell me about 50% of what she comes across in the store is total trite, overdone garbage & formula fiction.

OF course it’s all subjective. Today you could meet a person who says ERAGON is crap, but PERN books are “LYK OMG AWESOMENESS11!!!”

And, one week later you get a person telling you how much Pern books suck…

ART, as a whole, is subjective. And literature is art.

IMO, there are more true artists self/indie publishing & small press publishing. And more writers seeking commercial publishing are just looking to “get rich quick.”

A friend of mine told me she’d rather get commercially published because then her children’s stories can get made into a cartoon…

I’d be offended if someone made Wishful Thinking into a cartoon. Well an anime film maybe…but not like

a cutesy, disneyesque thing. That would bother me.