I’ve always been a publishing person, from the time I spent studying copyright pages in books around age 8 to creating what still look like sophisticated magazines as an adolescent using only a typewriter, pen and ink drawings, and Scotch tape, then photocopying the resulting layouts. I’ve worked in bookstores, typeset professionally, written for newspapers, compiled indexes (or indices if you so prefer), launched titles, designed and created reference works, redesigned magazines and journals, created web sites, and done a myriad other things in the realm of publishing.

And now, I’ve self-published my first novel.

I didn’t self-publish because the publishing process confuses, baffles, or overwhelms me. I don’t need a publisher to figure out discounting, rights retention, royalties, or the mechanics of publishing.

I did it precisely because I understand the traditional publishing process, and I didn’t want it or need it. Not for a work of fiction, at any rate.

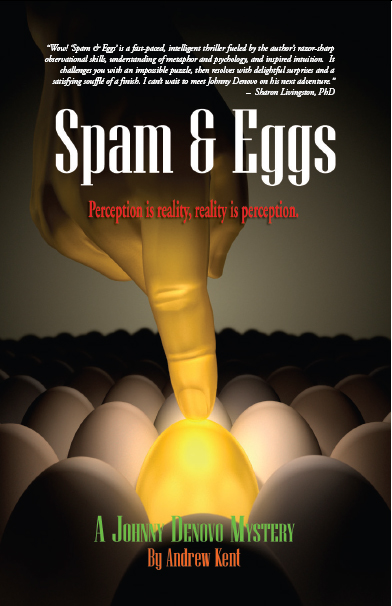

I’d been trying to write fiction off and on ever since high school, but university, work, family, and other interests made the efforts sporadic at best. A couple of years ago, I began writing yet another novel. Very quickly, I discovered the characters, plot devices, and time I needed for the work to really flow. Finally, in 2008, I finished my first complete novel, a mystery-thriller entitled, Spam & Eggs: A Johnny Denovo Mystery, which was published in February 2009 under the pen name Andrew Kent.

Because I liked the book so much, I decided to try the traditional publishing route for a few weeks to see if I could make a quick score, all the while lining everything up to begin self-publishing. It only took a little more evidence for me to decide to self-publish exclusively:

- There’s not much money in traditional publishing. Traditional publishing inserts layers of people between you and the customer, and each layer wants a cut. By the time you get your share, it’s a percentage of a percentage. And as far as having a bestseller or blockbuster goes, publishing through a major publisher increases your chances only slightly, by as little as 2%.

- Wanting a traditional publisher’s acceptance is probably even more vanity-driven than self-publishing (“Look at me! Harcourt accepted my manuscript!”). In fact, after separating the author from the commercial realities, vanity is largely the only thing left. Self-publishing is about really engaging the audience. There’s less vanity when you have skin in the game.

- Email has accelerated the submission and rejection game so much that neither agents nor authors are getting a true read on commercial opportunities this way. And, too often they’re looking for “the next [fill in the blank].”

- Even with a faster query process, it takes too long to get published through a traditional publisher. Authors have to wait anywhere from 2-7 years from an agent accepting them as a client to the publication of a first book — assuming a book emerges at all.

- New authors in this economy are low on the totem pole, especially for fiction titles. Agents and publishers want to bet on thoroughbreds. Few want to raise ponies.

- Old-fashioned consignment publishing is struggling. The economy has everyone in big, highly leveraged businesses (like consignment publishers) running scared.

- Amazon.com is the 700-pound gorilla in book sales these days. If it isn’t on Amazon, it has no commercial potential. Bookstores are only a piece of the puzzle.

- Even if a commercial publisher picks up your book, you’re still a small fish in a vast ocean, and the chances of success rest largely with you, yet with little chance of commensurate reward. And you close off important options a self-published author retains.

The Urban Elitist puts it very succinctly:

If I were to publish my novel with a publisher, the book’s chances for success would be slim and would be entirely dependent upon my own actions. If I were to self-publish my novel, the book’s chances for success would still be slim and would still be entirely dependent upon my own actions. Therefore, I wonder, rather than spending potentially years searching for an agent and/or publisher, might I be wiser simply to self-publish and give it my best shot.

I wanted a book, not a process. With self-publishing, there’s the sense of control — over the artwork, the rights, and the amount of effort expended. And then there’s the fun of doing the publishing work (I’m in the publishing business because I like doing these things). Self-publishing made a lot of sense.

I found a reputable self-publishing company, one of many out there. Their model is straightforward, and their owners and staff have the right attitude. You pay a fee for services, price your book and set the discount rate, and keep the margins. I don’t expect to make much money, but given the odds with other investments, this one has about as good a chance as any of working.

Is self-publishing the future? The Urban Elitist thinks it hints at changes in the industry. Consignment publishing emerged with the Great Depression so that bookstores could carry inventory without risk. Nowadays, anywhere from 10% to 50% of books are returned to their publishers. Returns are the bane of the consignment publishing industry. We’re familiar with this model, but there are major weaknesses in it. Amazon.com is exploiting these with the way it can fulfill orders, with its own print-on-demand services, and with the Kindle.

What about the stigma of self-publishing? Isn’t it just vanity publishing? It sure can be, and I avoid those books just as scrupulously as anyone. But more and more often, self-publishing is commercial publishing. More authors have calculated the risk:return ratio and are making the right choices. More authors have access to and know how to use the tools available. The stigma won’t last.

So, rather than dealing with rejections, negotiations, delays, long publisher contracts, or a bureaucratic and indifferent management of my account, in a matter of months (not years), I have a book that has garnered incredibly positive reviews, a readership base of acknowledged fans that spans many countries in the English-speaking world, and some interest in subsidiary rights, all within 2-3 months of publication. Best of all, I can concentrate on the sequel.

And guess what? I’m starting the process of publishing the sequel this week, and will have the book out by early Fall 2009. Beat that, consignment publisher!

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

My novel, Writing Therapy, was effectively self-published last November with the aid of a UK peer-review site, YouWriteOn.com. Having effectively been edited by a team of fellow writers, I was happy that it didn’t need the attentions of a traditional publishing house. I’ve retained complete control of my story – about a young girl writing a novel – and it’s worked. Reviews have been fantastic; sales good and getting better, and – best of all – the book has made the longlist for the YoungMinds Book of the Year Award, 2009.

Great explanation of why self publishing is a viable option for writers. I especially liked your point about traditional publishing being a vanity. I also decided that I was wasting my time seeking rejections from agents and publishers who had no inclination to actually read my work. I began self publishing almost 5 years ago and totally do not regret it.

Do I hear an echo in here?

Thanks for sharing. A very good explanation for why self-publishing is better. It made my understanding of it so much better.

Cheers

Freya

Wow. Great article. I love the vanity publishing comment. I keep thinking of going the traditional route so I can get some respect. I also chose to self publish the first time because of the time of the traditional process. The one caveat here is that self publishing means shelling out money (unless you’re lucky enough to have volunteers) to proofread the work. You can format the book yourself and create your own cover but I don’t think anyone is capable of editing their own work sufficiently.

Donald James Parker

Author of eight novels including Love Waits

I’ve been self-publishing for years, selling to publishers in other countries (now out in three languages and nine countries), and making my income on things other than books. I also have a novel/blog for teens in progress with a post every ten days at http://www.MaydenChronicles.com. I was big publisher published early in my career, and while the money was good at first (upfront), that was a fluke and not the traditional market. Even so, I made enough money on my first self-published to help put myself through college. Thanks, a great article!!!

An informative article that reinforces the suspicions we have about the traditional publishing route, especially the comment that it is just as much vanity driven. Like Tim Atkinson (above comment no. 1) I am also ‘essentially self-published’ by Youwriteon (more info on my historical fiction novel, at my website: http://home.cogeco.ca/~wrabbani).

The sales, for this debut novel, have been reasonably good, on the Internet. However, due to the 40 – 45% discount demand, I am unable to place the book in physical bookstores, unless I am willing to take a loss and write it off as publicity. This brings me to the point of the high printing costs of POD books, compared to similar ones put out by traditional publishers in bookstores, using the offset-printing method. Is there any way we can reduce the printing costs of our self-published, POD, books?

Wally Rabbani (Wallyr20045@cogeco.ca)

MPG Biddles are quoting some pretty good PoD/Low volume costs, minimum 100 books, for people in UK, or I have found (as I’m in Spain) Publidisa in Seville. They have an American born, Spanish raised, bilingual chap running their International Dep’t and their prices are amazing. They have sent me a sample book which looks good enough for me. Of course, delivery costs outside the printing country are pretty horrendous. I think if one searches hard enough one can find good prices. But this is real self publishing and just using PoD/low volume digital printers. Outside of printing you do everything yourself, your work, your profit.

With all due respect, Mr. Baum, your view here seems to raise as many questions as it answers. I’d like to offer just a few comments and ask a few questions. (I could do more.)

“1. …By the time you get your share, it’s a percentage of a percentage.”

This seems actively deceptive to me, in two ways. First, the share is always quite clear in a contract. A first-time mass-market paperback is 6-10% of cover price. Hardcover more like 10-15%. Higher if you are established and sell well. Second, what is the denominator? 10% of a million is a lot more than 50% or even 80% of 100. 100 is about the average for a PublishAmerica book, for example.

“And as far as having a bestseller or blockbuster goes, publishing through a major publisher increases your chances only slightly, by as little as 2%.”

Where did this number come from? I’d like to know how you calculated that. It’s an interesting assertion,and I can imagine ways to estimate it, but I’d like to hear yours.

“Wanting a traditional publisher’s acceptance is probably even more vanity-driven than self-publishing… There’s less vanity when you have skin in the game.”

Excuse me? Pardon me while I scoff. Deciding that your judgment is superior to a host of professionals in terms of writing, editing, publishing, marketing, selling, and cover design means you are LESS vanity-driven? This is merely insulting. Besides, ALL writers have their skin in the game — the fruit of their creativity. As writers, that’s the most important part — or should be.

“Even if a commercial publisher picks up your book, you’re still a small fish in a vast ocean, and the chances of success rest largely with you, yet with little chance of commensurate reward. And you close off important options a self-published author retains.”

True, but as a self-publisher, you close off options a major publisher can offer. What’s more, chances of success rest ENTIRELY with you, without the benefit of professional marketers and salespeople and an established distribution system. Granted, not everyone gets equal access to these benefits, but as a self-publisher I guarantee you won’t get any unless you hire them yourself, at your own expense.

Mr. Baum assumes that any sensible cost-benefit analysis leads to self-publishing. To a very large extent that depends on how much you value your time, and what you want to spend your time doing. Is it writing? Or something else?

Steve,

This article wasn’t written by Henry, but by me, Kent Anderson, writing under the pen name of Andrew Kent. So I’d like to respond.

The “percentage of a percentage” comment is legitimate. I’ve handled book contracts, read royalty statements, etc. There is a perception that authors get rich using traditional publishers. This is often far from the truth. The number who actually do is very small, most barely earn back any advance they received, and advances are shrinking. There is nothing “actively deceptive” about this comment at all. I can make 50% of the cover price on my novel if I sell it directly. That’s a lot more than the 6-10% you cite. As for sales, selling a million copies after returns is very rare. Of novels published in 2004 (when self-publishing couldn’t have skewed the figures much), 80% of the books published sold less than 99 copies; only 2.1% sold more than 5,000 copies (data published in 2006 in Publisher’s Weekly). The perception that traditional publishing is superior is driven by a huge availability error on the part of book shoppers — we go into bookstores, see stocked shelves, see sales, know bestseller titles, but that is all just the tip of a very deep iceberg. I used to work in bookstores. I’ve stripped covers off plenty of returns. We used to spend almost all of Saturday evenings doing this, big racks of returns. Customers don’t see this. Most traditionally published books are under water financially. Most traditionally published authors aren’t anywhere near getting rich, or even making a living at it directly from their book sales. Keeping 40-50% of my money as a self-published author means I only need to sell 1,000 copies to make the same amount as I would with a rare (2.1% of the time) hot selling novel, by industry standards.

As to the 2% statistic, see above.

Your response to the question about vanity — well, I personally think my judgment about cover design, text, etc., is as good as any publishing professional’s because I AM A PUBLISHING PROFESSIONAL. I’m an award-winning writer, editor, and designer. I’ve won regional, national, and international awards. Is my judgment as good as yours? I don’t know. Is it good enough to publish a book? Definitely.

And I have witnessed many times, first-hand, the vanity that drives the need to submit to traditional publishers. It is real. It has to do with the ability to say, “I’m publishing my book with Harcourt,” no matter the financial model, chances for success, or forthcoming grind. Even being accepted by an agent can lead to boasting and other symptoms of a vanity satisfied. But I’m not casting stones — most publishing is vanity-driven to a large extent. To say that self-publishing is more vanity driven than traditional publishing ignores basic human nature. It’s an unfair caricature because the vanity exists regardless of how you’re published. We just need to get beyond it as a differentiator.

As for whether the success of your book rests entirely with you, plenty of traditionally published authors say that it still does even when you’re with a traditional publisher. Marketing support is rare, often inadequate, and when it comes, it requires the author to do a lot. I see very little difference here for the vast majority of authors.

I personally like spending time marketing my books. It seems natural. And having worked with successful authors in my day job, I know the ones who succeed often are very hands-on. I think it comes down to whether you care about your book. J.K. Rowling and other major authors are renowned for how hands-on they get. Authors who give over this kind of control might not care as much, but that’s just speculation.

Andrew and Steve

Interesting discussion and I am going to throw in some comments. First, I am a professional writer and editor – have made my living (six figures) at it for 20 plus years. But that is in magazines and now the web.

I agree with Steve’s comment re percentage of a percentage. You get the royalty you get. However the real issue here is clarity of accounting. Traditional publishers not only DO NOT PROVIDE clarity into the numbers – at all – they also pay a minimum of six months and sometimes 18 months in arrears.

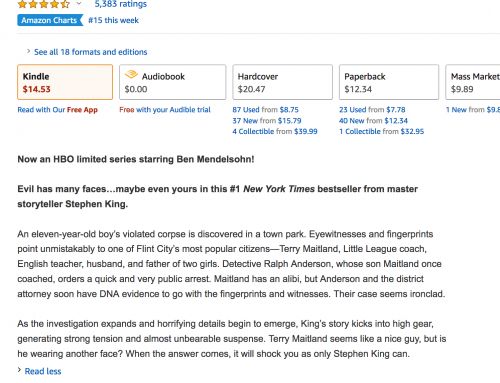

Bat I think aAndrew is right about the numbers and denominator. I have friends who are ‘best-selling’ authors – real ones – on NYT lists. They do not make six figures. Some barely make 5 (that is – they make less than $20,000 per year from an NYT best-seller). So that tells you how much the average author is making since the vast majority are not selling as much as that. Sure Stephen King does very well. But he’s Stephen King.

best-seller/blockbuster and 2% – this is frankly irrelevant – I don’t care if it is twice as likely with a traditional publisher – or even five times as likely – it is still not a whole lot more likely than winning the lottery.

Vanity – well – you both have points, but having met and interacted with and talked to many new york publishing house book editors – let’s just say that I don’t consider that much of a qualification. Every single magazine editor who has been in the field for more than four years is IMHO a better editor than any book editor with less than twice the experience.

So – do I think that 20-somethings at book publishers are good at selecting, advising, editing, reshaping, etc? No – I do not. And their world view is staggeringly narrow. What is more, this problem is getting worse and worse. As for marketing – pardon me while I fall over laughing. 95% plus of new books from traditional publishers got no marketing at all of any kind from the publisher – they are essentially giving up on them before they even start. Marketing is the responsibility of the author. So just how is it that we are supposed to value this? Most current writers who succeed are NOT the chosen ones or the best writers or the ones with the most compelling topics. They are the ones who also happen to, innately or through hard work, be good marketers.

Incidentally – if you go with the new breed of self publishing company you in fact DO get all the distribution advantages – some even more.

oops – make that MORE than twice the experience in the editor discussion!

Thanks for all of these great comments. The discussion is rich, even if the authors are not always! I agree that many of those going throug the slush pile don’t hold the values of the diversity of readers out there. Publishers want winners, yet so much gets lost in the assumptions around that that is.

For me, one of the greatest perks of self-publishing is giving away my books, such as the one at http://www.VenusForADay.com. Since the bulk of my income comes from working with individuals, not publishing books, giving away a book is an excellent sales tool. My reader/customer knows if we are the same kind of people/thinkers and so self-select. If we are on the same page (no pun intended), it’s great, because it is hard for my niche audience to find anyone else like me. I rise to the top very quickly. A book allows you to stand apart in specific ways. Retaining control of it, including the ability to give it away for free if it is part of a larger plan for income generation, is something I feel is well worth considering.

Thanks for the response, Kent. It does indeed give your name — though it also says “All posts by Henry Baum,” so you can understand my confusion.

I am well aware of the state of pay for most authors; I’m a published writer and my wife is an multiple-award-winning mystery and urban fantasy writer, and it’s a darn good thing I have a real job. However, I am also aware that you have to do far more work yourself to sell that stack of 1,000 self-published books you cite, and when you factor in the cost of that time, it’s not really as advantageous as you imply. Unless you like being a salesperson, of course. The average PublishAmerica book sells about 100, which means you make far less money than even the pittance that is the average advance for a first-time author (~$5000).

Your point on vanity does not convince, I’m afraid. Self-confidence is one thing; being certain of your ability in the face of compelling evidence otherwise is something else. You may be an exception; but you generalized to “self-published writers” and “traditionally published writers.” At the end of the day, being willing to let your work be judged by others is about being willing to take feedback and face relatively objective standards, even if it hurts. That doesn’t sound like vanity to me. Publishing is no more or less vanity-driven than any other job that requires you to get other people’s attention. If you want to know what drives published writers from a scientific point of view, see my (conventionally) published book Motivate Your Writing! from the University Press of New England. I’m a motivational psychologist and researcher by training, and spent some time studying what makes writers tick rigorously.

Your “speculation” about authors who “give over this kind of control might not care as much” is, frankly, insulting and categorically wrong in any case — and I have done my research here. Hands-on about what? The responsibility of the writer is to write, first and foremost, and to do it well. If you aren’t good at that, the rest is pointless. I don’t pretend to be an expert in the various diverse fields that make up publishing — but many self-published people do, and it reminds me of the old joke that a person who represents himself has a fool for a client. The percentage of people who can genuinely handle all aspects well is vanishingly small, and that is one of the most compelling reasons for the vast majority of people to consider mainstream publishing rather than self-publishing. There are good and legitimate reasons to self-publish — most obviously, when you have a topic of interest to a group of people too small to justify mass publication; or in special cases where you have other platforms from which to build your business. But for most fiction writers, I don’t see it justifying the effort unless, as you note about yourself, that you like to do it. Doesn’t guarantee quality in any case, but it means you enjoy the process more.

Steve,

I’m confused by the “stack of 1,000 self-published books” comment. You do realize almost everyone self-publishing now is using print-on-demand technology (not necessarily print-on-demand publishers… POD publishers and POD printers are two diff things), right? I mean we don’t have books sitting in our basements. We aren’t shipping them out on consignment to bookstores. We’re using Amazon.com and the like, and never physically touching a book (except the copies we buy for ourselves or to sell directly to readers off our sites, but that might be around 20 copies at a time for most indies.)

And it doesn’t MATTER what the average PublishAmerica book sells. If you’ve got it in your head that this is the way most indie authors are publishing, you’re mistaken. For example, right now I’m just on the Kindle, and though my price point is low to start building a reader base, I’ve sold over a thousand copies just on the Kindle since the end of November of my novella. (and generally speaking stand-alone novellas aren’t that popular to begin with) I’ve had another 4,000 copies downloaded from other places free. (The Kindle I have to charge for because of their policies, so you’re just paying for format, which is why the price is low right now.)

Nevertheless my kindle store sales rank is almost always in the top 2,000 (out of almost 300,000 books) and more than 2,000 of them are priced at my price point and below, since there are some publishers authorized to offer free books on Kindle.

If I was actively marketing it, I would be moving more copies. Now granted an 80 cent Kindle purchase is worlds away from a $14.95 trade paperback, BUT when we’re talking about exposure here and the possibility of sales, without very much personal marketing push at all, I’ve had over 5,000 readers in just a few short months.

A large percentage of those have been from word of mouth and my Amazon kindle sales ranking.

When I release my first print copy using Lightning Source for POD printing, and going largely through Amazon and a few other places, I absolutely expect to easily sell WAY more than 100 copies. And I will be making 4-5 times as much per book sold as I would through a traditional publisher. I’ve crunched the numbers.

My point here is that I’m not all that remarkable. I feel I’m a pretty good writer, but so are a lot of the “new indie authors.” We shouldn’t mistake self publishing with lack of publishing/writing savvy. And we shouldn’t forget that those who are NOT savvy are bringing down the sales averages.

When we talk about average sales being 100 copies on PublishAmerica we have to take into consideration all the truly crappy and completely unmarketed books dragging the averages down. It’s not a very good assessment of what a “good” book with “decent” marketing can do. And it’s most definitely not a very good assessment of what “great” book with “great” marketing can do. (On that second point I’ll let you know when I get there.)

Will I sell thousands of copies of my books? I absolutely fully expect to on every single book I release. I have no doubts I can.

As for “being willing to let your work be judged by others…” How on earth is putting something for sale in a major sales channel (like amazon) and marketing it and making sales, NOT being willing to let your work be judged by others? OH you meant those “special magical elf others” in NY who get to define what is worthy and what isn’t?

What they are defining is what they believe is “marketable.” In the last ten years I have read more crap published by NY publishing houses than I care to. Random House, Avon, Bantom… these are no longer indicators of a quality book. It’s only an indicator of a book someone thought they could make money off of which is not the same as literary value or quality. There are many beautiful books consistently rejected because they are “too literary” which isn’t code for “pretentious.” No, I haven’t written one of them, but I’m aware of many who have gotten rejections from publishers and agents lauding how wonderful it is but they don’t know how to market it.

This isn’t really a newsflash since they don’t seem to know how to market much of anything and marketing is primarily the author’s responsibility now in trad publishing.

And I can say personally there are two reasons I would have ever let a major publisher publish me. 1. They gave me a ridiculously amazingly high advance which would necessitate them actually marketing me. 2. To be able to say “so and so publishing me”

Number 1 is completely unreasonable and unlikely. Number 2 is vanity. Once I realized those were the only two reasons I’d ever choose trad publishing for my work, going indie became a big no-brainer. I also don’t think Mr. Kent was saying trad published writers were more vain than self-published, only that both are equally vain in different ways so vanity is a completely moot point and shouldn’t be used to say self-publishing is “bad” or all authors do it for “vanity.” As if trad published authors are above this. They aren’t.

Zoe — I was referring to Andrew Kent’s comment: “I only need to sell 1,000 copies to make the same amount as I would with a rare (2.1% of the time) hot selling novel.” My argument is that you are not comparing apples and oranges in terms of the work done by the writer. And POD is irrelevant to that argument — whether the books are in your basement or not, you are having to do work to sell them that would normally be done by a publisher’s organization and distributors. I am only citing PublishAmerica because they are the only self-publication venue that has proclaimed their sales enough for me to make a fair calculation. I am well aware of electronic media — as far back as 1999 I was at a dot-com working with higher education to put texts and content online. Furthermore, my wife is multiply published electronically. There is a lot of potential in electronic publishing and POD technologies, though they raise new difficulties as well — as in figuring out a way to have your book rise into visibility in the vast quantity of content out there.

I respect the fact that you have done moderately well with self-publication — for the record, the average mass market book is at least 5-10,000 copies printed, but not all sell — but you are still arguing by exception, which I am not. Of course there are people who know what they are doing, but they are not the norm, as even you yourself imply, when you note: “We shouldn’t mistake self publishing with lack of publishing/writing savvy. And we shouldn’t forget that those who are NOT savvy are bringing down the sales averages.” Of course. But the PublishAmerica numbers indicated that something like 95% or more of their authors were in fact not selling more than a handful, and most of the rest selling only a few handfuls. Similarly, your argument that major publishing houses (they’re not all in New York, contrary to the myth) often publish crap is also an argument by exception. Asserting that “Random House, Avon, Bantom [sic]…these are no longer indicators of a quality book” is simply hyperbole. They may not guarantee greatness, but they exclude poor and often mediocre quality, which is not true of self-publishing AS A WHOLE, which by definition has only one judge of worthiness for publication — the author.

I have been finding in general that the ranks of the self-published are remarkably contemptuous of professionals who have spent their lives learning to read, edit, and sell books. Not “special magical elf others” in any sense, but people who start with interest and ability and work on their craft, just like you. And while you express open contempt for their selecting what they believe is marketable, you then judge yourself by the idea that you sell. How is that different, pray tell? They are selecting books that sell, you are writing books you believe you can sell. And you are not correct in this presumption in any case. I know many editors and publishers, and they seek out good, readable books, which is after all the best kind of marketability. Yes, there is a pernicious habit of occasionally buying “safe” books from known authors or even celebrities for ridiculous advances, but that is merely overly conservative business sense. (And note that Stephen King takes minimal advances, because he knows that money given to him up front is money they don’t have to buy other books.) The hope is that the money from a John Grisham can keep the company going to buy other books, as indeed St. Martin’s lived off the James Herriott “All Creatures…” series for years. St. Martin’s didn’t buy that one expecting a gold mine, though they got one, and they dedicated some of their profits to acquiring new authors, including through things like the contest for unpublished authors’ novels they run through the Malice Domestic conference.

Of course they are not perfect. That’s why there are many publishers, and many agents, and a key part of joining mainstream publishing is finding which are the right fit for you. Any decent publisher or agent will tell you that an element of this is taste. Janet Reid, a good agent I know slightly, has even posted on her blog about a novel that she liked but didn’t know how to sell — and that’s her job, so if she can’t do it, the ethical thing is to turn it down. She since saw the book published, and bought it herself, very pleased that he has found someone who could sell it properly. That’s hardly the snooty, arrogant elitist type you seem to think populates New York.

Your reasons for avoiding a mainstream publisher are your own. Mine for wanting one is different from either of yours, and I’ve stated clearly what it is. I’ll say it again: Because I want to write and let other people manage the rest of the printing, publishing and distribution process as far as possible. I can, I have, and I will do additional marketing (I’ve published one book, and my wife has published a dozen after all — I know the realities). Please don’t insult my dedication to writing first as vanity. And for the record, Andrew Kent said EXACTLY that mainstream-published people are more driven by vanity, which is why the point came up in the first place. Here’s his point #2 above:

“Wanting a traditional publisher’s acceptance is probably even more vanity-driven than self-publishing (“Look at me! Harcourt accepted my manuscript!”). In fact, after separating the author from the commercial realities, vanity is largely the only thing left. Self-publishing is about really engaging the audience. There’s less vanity when you have skin in the game.”

And as I noted, I know exactly what motivates published authors of virtually any stripe, because I did the research (I’m a motivational psychologist and researcher by training). It’s in my book, and I refer to it on my LiveJournal blog I maintained while I was finding more to say about it. You can call it “vanity” if you like, but I don’t. It’s known in the literature as “Power Motive” but that is an unnecessarily negative label. It is truly the motive to influence, the satisfaction found in having an impact on others. This drives coaches, leaders, and writers. Mainstream published writers have an additional trait which may be germane to this discussion as well, which is an extraordinary ability to postpone satisfaction and channel their emotional influence drive for the long term rather than acting impulsively.

What I believe — and remember I have been responding to Mr. Kent’s assertions, and he raised the term — is that vanity is about believing no one else has the ability — let alone the right — to judge your work in any way. If you can prove me wrong, more power to you. But I respectfully suggest that very, very few writers of any level of popularity or experience would not benefit from a good editor. And many writers I know — good ones, bestselling ones — feel the same way. And the mainstream publishing community (including agents) is often a good place to find people who can help you. Even Shakespeare had his critics. If they can prove themselves with the market as you can or far more so, and they feel editing by their publisher is of assistance, I’m not sure where your argument goes.

We share the desire to engage an audience; we disagree about the methods to get from manuscript to reader. And in fact, I feel I am being demonized inappropriately here, because I have not, repeat NOT rejected self-publishing, whereas you and Mr. Kent seem to have wholly rejected the mainstream publishing world. I think there are times and places and books for which self-publication is entirely appropriate — indeed, what is a blog but a form of self-publication? That’s why I have one, to capture content that didn’t go into the book. But you and Mr. Kent seem to feel that there is no place where mainstream publishing is a better choice, and I think that is neither fair nor accurate. That is the heart of this discussion, in my view, rather than trading insults about who is more vain.

This post has generated a lively dialogue, that’s for sure. Mr. Kelner seems hung up on the “professionals judging your work” piece. I agree that it separates good authors from sloppy authors, but it doesn’t separate traditionally published authors from self-published authors. I’ll wager that good self-published writers get a lot of review and editorial help before they publish. Myself, I had at least five people read my book as favors — a professional journalist, a domain expert, a professional editor, a friend who reads voraciously and doesn’t pull punches, and a friend with really great taste and a knack for finding typos and continuity flaws. They didn’t do this professionally. I didn’t pay them, but they did a great job. My reviews have been very strong, and my Amazon ranking and local sales are the envy of some on certain days. For my second book, I’m having a few different people read it, and a couple of the same. The domain is different, so I have a different domain expert, but otherwise, I have help. I know I need it. I seek it, and I trust the opinions I’m getting. The results have exceeded expectations.

By the way, I know about delayed gratification and the motivations of authors, too. I agree that the desire to influence is in there.Basically, most writers write because they’re compelled to. They have things to say, and express themselves best through writing. Vanity comes later. I still think it exists, and is not a useful way to differentiate traditionally published authors from self-published authors, in the same way editorial help isn’t. Good authors will get help, good authors will keep their vanity in check, good authors will manage all these things well.

Shakespeare had his critics, but he worked his flaws out through drafts, rehearsals, and live performances. Often, he took his plays straight to the audience. He was the playwright, the theater owner (partly), and an actor (sometimes). He was pretty much self-published in the theater sense. So, that’s an interesting comparison, actually.

Time will tell how this all shakes out. As someone who has actually done it, who cares about my readers getting a book they’ll enjoy, who understands publishing, and who thinks change is afoot, I’ve made my choice.

What choice will you make?

Andrew, you would be more convincing if you read my comments thoroughly and responded to what I actually said. You have in fact supported and proved my point that having professionals review your work is useful, but again managed to insult those of us who made a different choice by implying that we don’t know any better. I, too, have done it, I care about my readers getting a book they’ll enjoy, I understand publishing from BOTH sides of the fence, and I also think change is afoot. Indeed, I’ve been part of it.

Again, you are arguing against what you imagine to be my point by exception, and I am not. You got help, and it mattered to you. You wrote: “’I’ll wager that good self-published writers get a lot of review and editorial help before they publish.” Yes — GOOD self-published writers. Well done, you’ve proved my point again, which was NOT that all self-publishing is bad, but that it takes more work on the part of the author to do it well. You carefully hedged your bet by referring to good self-published writers, whereas as you know perfectly well, the question is of the average across the whole field or at least the minimum standards, not the exceptions who know better.

I’ll wager that MOST self-published writers do not get a lot of competent review and editorial help. I add “competent,” because there is an issue here around who’s judgment is trustworthy. I’m not “hung up” on this point, it is the central argument around the difference between the typical self-published work and the typical mainstream-published work. You picked a professional editor and a professional journalist as well as others you trusted. Good for you.

I say again: I have NOT rejected self-publishing; you have rejected mainstream publishing. And I think with inadequate reason for the majority of novel-length fiction writers. If you like what you do and have found ways to make it work, more power to you. That’s what the founders of Random House did, too. You were the one who raised the point about vanity and said that those published in the mainstream fashion were likely to be more vain. I’m glad you’ve backed off from that point. But editorial help IS a distinguisher. You have assembled your own team; mainstream authors don’t have to. That’s been my central reason for going with the mainstream, as I have said repeatedly.

By the way, Shakespeare didn’t have any other options in his day, so it’s not quite the same as today, but he did show his work to other successful, proven professionals and received criticism from his friends and colleagues who had proven capability.

I know what I’m doing and why. Good luck to you.

Steve,

I read your points and showed you where points of agreement existed, where other points were moot, etc. I was trying to get you to let go of the rawhide, man. I didn’t back off anything, but extended my thoughts to show you there wasn’t the gap you perceived.

You’re correct, I have rejected mainstream publishing for fiction — because in the right hands, the gap between self-publishing and traditional publishing is vanishingly small when they are done right. For non-fiction, I think things are a bit different, but I’m still assembling my thoughts on that subject. I might post on that topic someday.

By the way, I can’t find your blog. If it’s the one I found, you haven’t updated it in over a year. Also, I can’t find a published book by you. Can you point me to it?

Andrew, I appreciate the effort, but we’re still talking at different ends of the spectrum, since I would suggest that there is a gap you _don’t_ perceive! And the gap is largest in fiction, especially at novel-length.

You are correct, I haven’t updated my blog in a year; unlike too many bloggers, I set as my principle that unless I was adding something substantive on the subject, I wasn’t going to add anything, and I haven’t had anything different to say on the writer & motivation research in a while, save one speech I did for the Romance Writers of America I may write up on “writer’s block.” I have another nonfiction book in the works (which I refer to in the blog), but that has been set aside while I work on other things during my days and nights, including my own novel-length fiction.

As for my book: http://tinyurl.com/olywca

If you post on nonfiction, I’m happy to chime in. What I have seen is that there are many areas which are a small but dedicated audience, e.g., Civil War buffs, writing on something like “ammunition use at Gettysburg,” which isn’t big enough to justify mass distribution, but for which there are probably five hundred dedicated readers who will buy it and argue about it relentlessly. This is an ideal place to self-publish, because there are an infinite number of similar niches.

The other major category is another kind of specialty nonfiction where there is already a very good platform for marketing and distribution which makes mainstream publishing redundant. I knew the guy who published the “Motley Fool Investment Guide,” for example. Motley Fool Books is their own publishing brand, obviously, because between TV, websites, etc., they could even do a mass market printing and work the finances entirely through their own extant system. In that case they had built most of the infrastructure and the rest was an incremental cost. In a sense, they are a larger-scale version of the Civil War example — if you have a niche AND the audience already on hand, it’s much easier.

I still don’t understand this “norm” business you are referring to, Steve. Who CARES what the norm is? If Mr. Kent can do it to his satisfaction, and I can do it to my satisfaction, and other indies can do it to their satisfaction, whether their goals are higher or lower than ours, who cares? Why are you so wrapped up in what the “norm” is? How does the norm affect one individual person’s success, failure, or happiness?

Most of the time when I hear arguments against self publishing, and especially when I was first deciding to go that route, I had many naysayers saying exactly the kinds of things you’re saying about “the norm.”

Well about 90% of small businesses fail too. (may actually be higher than that.) But people still start businesses in droves. Because it’s respectable to try to build something on your own. Opening a flower shop is respectable succeed or fail. Why not indie publishing? You’d think most self publishers were opening brothels. Why is there such a mental roadblock to this? And why does it matter to you what the norm is? If I had listened to all the naysayers about the “norm” I wouldn’t be doing this. And I absolutely believe this is how I’m supposed to be publishing, because like Mr. Kent, I love the act of publishing and the process itself. I love building something that is totally mine.

And no, NY publishers do not exclude poor and mediocre books. When I only find 1 out of 5 books that I read from NY publishers on average decent enough to slog through the entire book… I consider that a quality control problem. My point is only that NY is not a high enough or consistent enough arbiter of quality for me to consider them any kind of gold standard that I have to pander to. Or to care for their opinion. They aren’t “the enemy,” they’re just… irrelevant to me.

You misunderstand me. I do not have contempt for these NY publishing people, my contempt is for the people who have elevated them to gods, who don’t realize they are fallible, and who are trying to equate quality with marketability. They are two separate standards, and you can have quality AND marketability, but quite often what is currently coming out of NY is marketability without quality. IMO. I too have spent years reading, writing and editing. I’m not saying I could do their job better (I think NY publishing is a broken system and nobody could do it better under the current rules and procedures), but I sure as hell wouldn’t do it worse.

Publishers don’t have to go to a special school for publishing. It’s not like being a doctor or a lawyer, so I feel it’s a mistake to elevate these people above what they are. By their own admission they’re running a giant gambling casino. I’ve read NY times articles where editors have been quoted talking about selecting books as some sort of mystical process and they dont’ know what will sell, etc. Except for Harlequin, most of them aren’t doing any real demographics research.

And actually as a company I do have respect for Harlequin, they’ve been one of the most forward thinking brand name publishers out there. I may not care for many of the books they produce, but they’ve got business sense and I can respect that. But when a publisher neither shows much business sense, nor much taste, what do you expect me to do with that?

And you mentioning the good agent who likes a book but can’t sell it is exactly why going indie is a good choice for many writers. It is harder and harder now for many GOOD writers to get published, even many writers who actually are marketable, just maybe not MASS marketable. But that’s the wrong barometer for whether or not a book should be published. And it’s most definitely the wrong barometer for other writers to use to judge each other.

Most fiction writers will never ever make a living at this. Even most NY pubbed fiction writers. The second I learned that, was the second I decided for sure to go indie. Why? Because for me, the only real motivation to give over creative control like that would be money (i.e. it’s a business decision.) Otherwise, I’m going to just create what I’m going to create, and get the best help I can get to make it as good as it can be (easily as good as most of what NY is putting out), and get it out there to find an audience.

As for the argument “why not choose a small publisher?” (I know you haven’t mentioned this, it’s just a general argument.) Well there isn’t a thing a small publisher can do for me that I can’t do for myself. Most good small published books sell a few thousand copies. Well *I* can do that. Because I’m competent enough to do it.

And lest you think I’m “angry” that someone has failed to recognize my “supposed genius,” I always wanted to be indie. It just took me awhile to take the plunge. I was raised in an entrepreneurial family. My grandfather owned a printing company. My dad ran several small businesses before he found the one that succeeded for him, and that entrepreneurial bug has passed to me.

If people stopped slamming self publishing and those who choose to do it tomorrow, I wouldn’t have problem one with NY publishing. I don’t care what they do or how they do it, as long as they aren’t routinely held up as higher than they are, to make me look less than what I am.

And I never said they were snooty, arrogant, or elitist. If they were any of those things, they’d be publishing more higher quality work. I believe they are turning publishing into widget-production. As I’ve said elsewhere, you can’t be snobby AND mass market, that’s contradictory.

I also didn’t say you personally were vain. I said vanity exists in trad publishing as much as self publishing. People like to be validated and recognized. It’s totally normal human nature to say “look at me, I did this.” And some people choose a certain way of doing things for that reason as a higher motivator than others. This isn’t a sin or a crime. And I didn’t pretend to know your personal motivations or where vanity ranks on the list for you if at all.

If you can take that statement and be offended by it, then you can see why I find half of the arguments against self-publishing offensive. And despite your later arguments that you aren’t slamming all self publishers, or self publishing, but just the bad books… well really, what can myself or Mr. Kent do about anyone else’s publishing choices? That’s like holding a retail store owner responsible for the actions of other retail store owners. Each effort has to be judged on it’s own merit, if it’s to be judged at all, but making sweeping generalizations about self publishing and then getting upset about sweeping generalizations about trad publishing… well that’s a little goofy, no?

Mr. Kent said “probably” more driven by vanity. And in many cases I think he’s right. If you hang out on many writer discussion forums populated by a lot of non-published writers who want NY contracts, you’ll see what we mean. There seems to be a LOT of stock put in WHO your agent is and WHO your publisher is. And not just based on it being the best fit, but based on the ego-validation of being able to say: “Oh yeah, Simon and Schuster is publishing me.” That’s no different than the vanity ascribed to self pubbers.

All this is about is the fact that we find it annoying that publishing our own books with our name on it is somehow vain, but if I were to start a clothing line and put my name on the clothes as the brand name, no one would jump up and down about how vain I was. This is a fake issue. That’s the point. Not who is “more vain.”

Mr. Kent mentioned himself that it’s a fake distinction. I mentioned the same thing. But you choose not to hear that, and instead decide we’re both name-calling.

As to self publishers trying to escape criticism, and editors… I had an editor go over my work, and I had many beta and critique readers besides that. I am not afraid of criticism. But I will say… I don’t think a corporation necessarily has more value in their opinion than another outside expert, especially when *I* personally do not value the quality of the bulk of what they put out. As an indie what *I* value and think is quality is important. I’m not going to live other people’s values, and other people’s likes and dislikes.

And going back to my sales numbers, no I do not feel that quality and numbers are necessarily equivalent. But one of the primary arguments against self pubbing is how terribly difficult it is to sell more than a hundred copies. And I think that’s a fake argument too. Depends on the person, the book, the marketing savvy, etc. And most authors no matter how they are published, most marketing falls to them. Brick and mortar stores aren’t the distribution panacea they once were. I’m not even selling to those customers. My customers are online. Those are the people I’m after…people like me, who shop like me. And that is a large and growing consumer base.

Awesome comment, Zoe. You raise a separate point I want to expand, and it’s about brick-and-mortar bookstores. There seem to be two problems with them these days. First, their selection is homogeneous. Second, the bookstore motif of today veers customers away from books. I’m saying this as someone who used to work for a chain bookstore. When I did, we had a store that was all about books, and the staff was excellent (patting self on back now I fear). We read books voraciously, knew author lists, loved looking up and securing titles from microfiche (showing my age), etc. People came in for books, interacted with us about books, and left carrying books.

Nowadays, if the DVDs, CDs, coffees, gift aisles, greeting cards, and cafe don’t distract you, you might just see books. Real books. And if the staff didn’t have to worry about stocking toys, mugs, food, movies, and music, they might actually get to know books.

There are still great bookstores around, but more and more are conglomerations of consumables. Even my local one is a mixed bag. Some of the staff definitely “get it,” and there are some real book people there, but others don’t. I’m lucky to have a local shop that’s as good as they are, even if it’s not the halcyon days of 15 years ago. They still deal in too many distractions (cafe, gift shop, greeting cards, etc.) for my tastes. It’s a shame, and a slippery slope bookstores can’t/won’t jump off. Bookstore staffs used to be the difference — they made “Wicked” a runaway bestseller almost on their own back in the early 1990s, for example. A furrowed brow from a trusted cashier could make you put a book back, and an enthusiastic recommendation could put an unanticipated book into your hands. I doubt they could do the same today.

When even the bookstores aren’t geared to deal in books, it’s no surprise that a) bookstores don’t matter as much to a book’s success, and b) that authors who sense narrow tastes among major publishers take matters into their own hands.

Hey Andrew, don’t you mean “awesome novel-length post?” hahaha. I am long-winded, my eyes glazed over just re-reading my comment. My friend April Hamilton wrote a really interesting blog post called Big Chain Bookstore Deathwatch.

In it, she makes a comparison between big chain music stores failing and big chain bookstores failing. The same situations were in place. The music itself couldn’t turn a strong enough profit, so they had to bring in “other stuff” to compensate, sort of like all the front of the store crap in bookstores now. It got to the point where indie music stores had unique offerings and knowledgeable staff, online had unlimited selection, and walmart had better price. If you wanted something quirky you either went to an indie store specializing in that type of thing or online. If you wanted something popular but cheap, you went to Walmart.

Same exact situation with books now. Barnes and Noble isn’t really a common sense place to shop for books anymore. If I want something they dont’ have, I’ll just order it online. If I want a bestseller, it’s cheaper at walmart. Barnes and Noble isn’t a mom and pop shop, so I can feel no guilt going to walmart over B&N. (Even if B&N is struggling.)

Right now I’m in a debate elsewhere with someone who despite how much the chain bookstores are struggling says that’s still where most of the sales of books happen. She is someone preaching to the trad-publishing crowd. The people really desperate to believe that there are still really good opportunities and options for them if they start hunting an agent today. But considering how these bookstores are failing… if most books are REALLY still being sold in brick and mortar chain bookstores, then we ALL have more things to worry about. Such as… why apparently no one is buying books.

I look forward to a day when we have indie coffee shops with POD book machines in them. In fact I’d love to run one of those with my husband someday. You’ve got that cool atmosphere and book lovers, and endless selection. Bands on the weekends, book discussion groups during the week. I don’t think we can really get back to what we had with bookstores, but I think we could in some new way mimic the “experience.”

Zoe — I think you misunderstand my intent and my terms, but perhaps I was slipping into an academic definition of norm. The purpose of a norm is not to flatten the range, but to indicate the center, the average that typically sits in the middle of a bell curve. A “norm” does not exclude anyone. All I’m saying is that for those who do not know where to begin in the business, it often makes more sense to start at the norm (and explore from there) than to jump in at one end of the pool and hope it isn’t too deep when you don’t know how to swim!

You may feel that everyone should learn how to swim. Fair enough, but that view is not held by everyone, nor is everyone sufficiently skilled to enjoy it. I hate to see someone devote time and money to something which was unlikely to succeed from the start, when they could do it differently — and that could be an informed approach to self-publishing as well. I have seen people fail to do their research on ANY kind of publishing, and suffer for it.

As it happens, I am a business consultant, and I would say something very similar to any entrepreneur: 90% of small businesses do indeed fail, and of those which succeed, most make no money for the first two years. That’s NOT saying “don’t start a small business.” The intent — my intent — is to provide a realistic sense of risk, and encourage people to explore their options thoroughly in order to be in the 10% rather than the 90%. My objection to many of the self-publishing marketers out there is that they do NOT provide the guidance necessary either to evaluate the risk or to mitigate it. Some of the most notorious “self-publishing services” out there are actively misleading about this, and take advantage of the writer who has not studied the business. (Don’t take my word for it — see the Predators and Editors website.) Rather than a rah-rah approach to this, I’d really rather prefer a realistic assessment of what self-publishing really entails and how to make the most of it. We could provide a contrast quite easily between positives and negatives of both.

You seem to be implying that I have a mental block about this, and that I am making sweeping generalizations about self-publishing while objecting to the same about mainstream publishing. Not so. I have said self-publishing is a viable alternative under a number of circumstances, some of which I specified in my last post, whereas neither you nor Mr. Anderson (I keep switching the names – sorry, Kent) had _anything_ good to say about mainstream publishers until your last two posts. Mr. Anderson implied that there was a narrow gap between self-published and mainstream publishing in some situations; and you praised Harlequin — on which point I heartily agree with you. I can criticize the mainstream publishing business as well — and indeed I have publicly in other places. I think the business model has problems. I also don’t see a truly viable replacement — yet. You think otherwise, and that’s fine. But in the meantime, there must be discussion with strengths and weaknesses of BOTH sides, so when the tipping point really happens, people can take advantage of it. Furthermore, the two are not mutually exclusive. On a LinkedIn site I am on, a writer went into some detail about what he had done both ways, and for some books he stuck to the mainstream publishers, and for others he went self-pub. But he knew exactly what he was talking about for both, which is unusual — and he had made some mistakes on both sides as well.

As for the “vanity” argument, I quoted Mr. Anderson’s full paragraph. If you don’t see why I might object to that as someone who HAS published with a mainstream publisher (admittedly a small academic press not in New York), let’s move the vanity argument aside, because clearly it is a hot-button that is getting in the way of discussion.

As for hanging out on lists with nonpublished writers, I have been on many. I have been part of the Internet Chapter of Sisters in Crime since it was on GEnie, back in the mid-90s. (I was president of the chapter for two years recently.) My blog attracted some minor amount of attention on LiveJournal.

So let me come back to my main point in its simplest form, which frankly both you and Mr. Anderson are supporting quite well: Self-publishing is HARD! You need to do your own work on a lot of things, or you run the risk of letting your vanity be your editor. GOOD self-published writers get lots of solid, trustworthy support in their efforts, which they pay for either by money or by time and friendship, but at any rate I think you both suggest that a professional approach to self-publishing should NOT be you by your lonesome. Mainstream publishing also takes effort, but in different areas, and generally in a narrower time and narrower set of skills. In my view, you can save a lot of effort by going mainstream, but both approaches benefit from good information.

That’s why I keep saying that you and Mr. Anderson are arguing by exception. I never denied that the smart, savvy, experienced person can do moderately well in self-publishing — though the goal in MY view is to be able to make a living from it, as writers once were able to do in mainstream publishing as recently as the 1960s and 1970s. What I’m saying is that MOST writers are going to have to learn to do a lot of new things to even start on self-publishing competently, and for MANY (and in my view, most) writers of novel-length fiction, it might not be worth it, if their goal is to sell more than a few hundred or even a few thousand books. If that is a controversial statement, I would like to know why!

Steve,

You make valid points but I guess the reason you came off the way you did is because it’s my impression that a lot of people who read this blog, *are* somewhat savvy. This isn’t the first time most of them are dipping their toes in the pool. Many of us are already deep into the process of self publishing, most of us care about quality. For most of us the term “indie author” means something.

We aren’t total noobs or dabblers or whatever. And so it leaves me wondering “who” you are addressing your comments to? A lot of your arguments are the same things we’ve heard elsewhere, and we still chose to do things this way. If you’re not talking TO me or TO Andrew about what we specifically are doing, then who are you talking to? It feels like you expect us somehow to take responsibility for what every other self publishing author does, or to feel shame for the stigma that isn’t our fault.

That may not be your intention, but I’m left wondering still.

I don’t think everyone should learn to swim. I don’t think everyone should self publish. Self publishing is only really right for a very specific personality type. (just like all entrepreneurial ventures) Most human beings just are not that entrepreneurial. They do better with more structure and that’s fine. Nothing wrong with that. But why *I* should personally concern myself with that as any kind of marker for my own behavior, I’ll never know.

And that likely isn’t your intention, but I’ve had many well-meaning people who have tried to dissuade me from self publishing. Because it isnt’ what *they* would do. I, on the other hand, have never told someone they should self publish unless it seemed like something they really wanted and seemed suited for. I don’t automatically assume my path should be everyone’s path, but that’s not true of most trad published authors, who do seem to feel that everyone should do things their way or it isn’t valid.

I agree with what you’re saying with regards to self publishing services. I personally won’t be using something like Lulu or Authorhouse or Xlibris. (which isn’t to say these are bad companies, just that I don’t consider it truly SELF publishing if you don’ t own your own ISBN numbers and have your own imprint label on your books.) When I release in print, I’ll be using Lightning Source which is a POD printer used by many other standard publishers for backlist, and for smaller publishers. LSI has the highest quality for POD paper/binding/cover that I’ve seen and a fair price. They’ve also got partnerships with Amazon.com as well as Ingram, Baker and Taylor, and many other distributors.

I agree also that before someone makes the decision to self publish IF their goal is to make ANY money, (as opposed to just self publishing as a hobby or for family and friends), then they need to go in with eyes wide open and be as educated as possible about the issues.

But just because you read an article that’s positive about self publishing doesn’t mean it’s discouraging research. Many of the readers of blogs such as this one are either currently indies or seriously considering becoming indies. Most people who are in the audience for a blog like this are not delusional people and weigh the decision to self publish carefully before moving forward. And the people who don’t have any sense at all about it but only pie in the sky dreams, well all the warnings in the world won’t dissuade them.

And we dont’ really have a lot of great things to go on about mainstream publishers, because this blog isn’t ABOUT mainstream publishing. Do you expect most traditional publishing outlets to go on and on favorably about self publishing? Or to give it equal time? That’s not what the blog is about. Why are we obligated to share the “good parts” of trad publishing? They weren’t good enough benefits for us to go that direction. Sure, trad publishing is right for a lot of people, but if they’re on this blog or other sites and blogs like it, chances are good they already have their doubts about that.

Every time I say something with regards to self publishing I’m not going to write a disclaimer about how people need to research further. That should be common sense. And if it isn’t, no amount of my saying it would do any good anyway.

I also haven’t said indie publishing should “replace” trad publishing. In a perfect world I would say, let trad publishing field the blockbusters and let indies do everything else, and let writers stop being such jackasses to each other over the issue. There is an important place for trad publishing, but when mainstream NY publishing is defined as the only ‘valid’ publishing by MANY people (even if not you) then there is a problem. IMO.

In filmmaking there are the big blockbuster making studios and indie filmmakers. They co-exist happily and peacefully. Indie filmmakers are even allowed to be nominated for Oscars. They have well respected festivals like Sundance. This is ALL I want for indie authors, an environment like what indie filmmakers get. Rather than snobbery, constant snubbing, and straw men that don’t apply to me, Mr. Kent, or many other indie authors.

As for the goal to “make a living” from writing fiction. (nonfiction is a whole separate discussion) It is incredibly difficult for most even mainstream NY published authors to make a living writing fiction. Even a few authors who have hit bestseller lists aren’t “making a living.” And why do you assume my goal isn’t to make a living? While fiction isn’t the only plate I’m spinning, I do expect within the next decade, with my entire backlist available and good writing and marketing, to be making respectable money for fiction.

And IMO, a GOOD indie, even one that wants NY, stands a stronger change ‘starting out” indie, building a platform, building buzz, THEN selling, when they are attractive enough to a mainstream publisher to warrant a high advance and a strong marketing push.

As it stands right now, many people who get mainstream NY publishing contracts are published by NY but they aren’t marketed by NY. Unless they get lucky, or have crazy mad marketing skills on their own, they aren’t going to move many books. But either way, just having a single book spine face out on bookstore shelves, isn’t likely to put a big enough dent in their sales to move them high enough up the charts to warrant high enough advances for them to live on.

The most likely scenario is they’ll get stuck low on the midlist, never break out, and eventually get dropped by their publisher or become disillusioned and cynical about the whole thing.

If an author sold 10,000 copies with a NY pub, it’s no big deal, and even disappointing. EVEN IF a large majority of those sales came about by the author’s own work to build buzz for the book. If an author sold that many by themselves, then NY in many cases sees the dollar signs. Then they *might* offer an actually decent contract which forces them to market the work and push it, which results in much higher sales and higher future advances. i.e. a fiction writing career that a sane person can actually *call* a career.

But when NY doesn’t push a book, just let’s it dangle and hang out spine face out on some bookstore shelves, it’s to the author’s detriment and to the detriment of any future career they might hope to have. Further, NY does not “build careers” any longer except for a very very select few. It often takes a writer 5-10 books to really start to build up a strong audience.

Most NY pubs aren’t going to give you that much of a shot. You might get 2 or three books if you’re lucky to build a strong enough audience to be able to stay on their shrinking midlist… or as I like to call it: “author death row.” Once they drop you, you are damaged goods, and good luck getting a second publisher under that same writing name.

IMO if you really want to make money, your best bet is being a savvy indie, building your audience until you get to the point where you can break out and THEN move to the big leagues, if you so choose. Trying to play in the majors too soon is career suicide in this publishing climate, IMO.

and sorry that was a novel. I never have a clear view of how long my post is going to be until I click submit. It looks different in the tiny window.

Steve,

I hate to quibble, but you say you’ve published with a mainstream publisher. Actually, you’ve published with a small university press consortium, not a mainstream commercial publisher. I want to clarify this because it matters to the perceptions of people reading these exchanges. I’ve published in academic journals, scholarly books, etc. To me, that doesn’t qualify as “mainstream,” even though I’ve probably reached a large audience on occasion (hard to tell in the journal space, but I’ve published multiple times in a very large circulation journal, which may reach 500K people each issue, but I still don’t think that’s mainstream since it’s very domain-bounded). I think you’re much closer to an indie author than you might care to admit. A small ($2.5 million in revenue) university press consortium in New England is a small press, not a mainstream publisher. Judging from its catalog, it’s not mainstream. And some of the cover images look, um, not that far above the quality a good indie author can attain flying solo. I’m just sayin’.

It’s my opinion that your title probably would have succeeded very well today as an indie author offering if you marketed it correctly. You wrote in a sweet spot for these things. And, you could keep more of the money! Imagine that. In fact, you’d probably quadruple whatever you’re making now (assuming that you’re getting any royalties these days — for a niche and/or academic title, I’ll bet your royalty statements are still underwater with returns and hold-backs from the publisher; you probably received one check at the beginning from the initial sales burst, and then nada. Tell me I’m wrong. Also, tell me how much marketing and PR support you’re getting from them these days. I’ll bet it’s nada, as well.)

Bragging that HOW you were published sets you apart dramatically and using that as a cudgel in these discussions is pointless. WHAT you published looks interesting enough. Plus, I continue to think the differences are thin and thinning between good indie authors and good traditional authors, especially those with small presses but even many mid-list authors with the big shops.

Kent,

Seems to me I said I was published with a “small academic press.” I used the term “mainstream” rather than “traditional,” which I think has an implied criticism and isn’t really accurate anyway (since the big publishers are using POD and Kindle, etc.). So far, the publisher/editor/distributor combination is still the mainstream, in the sense of being the dominant approach to publishing. I see no need to compare resumes; I was explaining to Ms. Winters why I found your point #2 an accusation of vanity, no more — and no less. In any case, a small press (and that’s a whole ‘nother discussion, because I see that as the future of publishing) is not the same as self-publishing.

Steve,

I think small presses are a big part of the future of publishing too. Though, I will argue with you on the “not the same as self publishing” part (just cause I like to argue 😛 ) Sometimes the lines are pretty blurry there. Obviously a small press with a staff of 3 people is different from someone publishing on Lulu…but what about a micropress? Which is just the smallest of small presses? Say you have a one person show that publishes other people’s fiction, a micropress. Then you have another one person show that is publishing their own fiction, still a micropress. Whether the “talent” comes in-house or is hired out, doesn’t change the form of the business.

A micropress is a micropress is a micropress. Same with small press, or indie press, or whatever people are calling themselves these days.

Also, one of my friends, Moriah Jovan is a self publisher, BUT she also publishes other people now in addition. She is running a small press, but she’s also self publishing her own work. So I’m thinking the distinctions between small press, micropress, and self publishing are going to get increasingly thin. You’ll always be able to point to a larger small press that publishes other people and hold them next so someone self publishing using Lulu and point to how “different” they are, but the differences become vanishingly smaller when we meet in the middle somewhere.

One other question though… if you see small publishing as the future of publishing, then exactly how are they going to be able, as a small press, to market more effectively and get into more sales venues than a savvy self publisher? A lot of small presses have a hard time getting their books into bookstores as well. If mostly the same outlets are open to them that are open to self publishers, then how do they become a better option than going indie, except for the person who either:

A. doesn’t want to handle the business end of things.

or

B. isnt’ competent to handle those areas effective.

?

I think when you begin saying that a small press is better in some way than self-publishing, the thin ice is gone and you’re in the water. Here’s why I say that. First, the marketing support of a small press is probably as close to nil as it can get. Second, the distribution advantages are certainly non-existent. Third, the publisher brand and power is not a differentiator. Fourth, as I noted above, the design capabilities of at least the cover don’t compare with the embossed, metallic-inked, custom illustration covers of mainstream fiction or non-fiction (the interior designs tend to be professional, but even then I’ve seen some pretty awful ones, too). Fifth, if you argue that the editorial process is superior, that’s just a choice — as a self-published author, for a few hundred dollars, I can match that small press’ manuscript editor, and if I knows some peoples, I can get an expert to read my book and advise me. The one area where there is necessarily a difference is that the small press assumes some risk by taking on your title. Increasingly, with POD and the large-scale utilization of that for niche titles, even that risk is about the same as for a self-publisher. Finally, you could argue that you’ve gained acceptance from a publisher, and I say, well, for people who still have a mental model of the publishing industry that’s even 5 years out of date, they’ll think it’s a big deal; for people on this site and their ilk, the differences are probably seen as tissue-thin if they exist at all for any particular title.

I would be surprised if regular readers of and contributors to the Self-Publishing Review (is there a way to italicize in comments?) DIDN’T think the difference was razor-thin. I happen to feel otherwise, and to me the facts of the case are compelling. You feel otherwise, partially because you weight issues differently than I do.

For example: I never said I couldn’t find good editors, illustrators, etc. But with a publisher (1) I don’t have to, and (2) I don’t have to pay for it myself. Let me say one more time: I want to spend my time writing and doing selected kinds of marketing. Period. I have more than my share of the Achievement Motive that drives entrepreneurs, but it isn’t aimed that way. (See Zoe’s point A in post #32, in fact.) Saying that, for example, I can find all sorts of experts to read my book if I want to go to the trouble of finding them and paying them isn’t really convincing me it’s a “razor-thin” difference — you’re just saying that if I want to I could make myself a publisher. Well, of course I can. I’ve known that for decades now. Indeed, in my case, I have better access than many, since my wife is already an award-winning author and bestselling editor, and I am friends with numerous excellent and erudite writers and artists, but that is NOT true of the vast majority of people who want to write and publish, so the general point stands — if you don’t want to be your own publishing company AND learn the myriad of skills required to be good at it, then don’t self-publish!