Editor’s Note: This post welcomes Bonnie Kozek, author of the novel Threshold, to the Self-Publishing Review.

Editor’s Note: This post welcomes Bonnie Kozek, author of the novel Threshold, to the Self-Publishing Review.

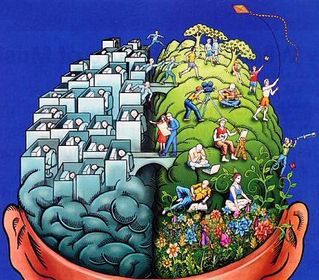

In the 1960s, Roger Wolcott Sperry, a neuropsychologist and neurobiologist, developed a revolutionary concept about the brain called the Right brain/Left brain or “split-brain” theory. (In 1981 Sperry received the Nobel Prize for this research.) His theory challenged the established and accepted view that the brain, although comprised of two hemispheres, was basically one entity with interchangeable parts.

Through experimentation, Sperry showed that instead of being composed of interchangeable parts, the circuits of the brain are largely hardwired – each nerve cell tagged with its own individuality early in embryonic development. Once tagged, the cell becomes fixed – no longer modifiable. Further, Sperry showed that if the two hemispheres of the brain are separated by severing the band of fibers that connects them, the transfer of information between the hemispheres stops. Thus, the coexistence in the same individual of two functionally different brains was demonstrated. The Left hemisphere is the one with speech, and is dominant in all activities involving language, arithmetic, and analysis. The Right hemisphere, although mute and capable only of simple addition (up to about 20) is superior to the Left in, among other things, spatial comprehension – in understanding maps or recognizing faces, for example. Until Sperry’s experiments, it was doubted whether the Right hemisphere was conscious.

But Sperry proved that a conscious mind exists in each hemisphere. By devising ways of communicating with the Right hemisphere, Sperry showed that this hemisphere is, to quote him: “. . . indeed a conscious system in its own right, perceiving, thinking, remembering, reasoning, willing, and emoting, all at a characteristically human level, and … both the Left and the Right hemisphere may be conscious simultaneously in different, even in mutually conflicting, mental experiences that run along in parallel.” The discovery of a dual consciousness opened up new doors of brain research. And today, these concepts continue to be explored by biologists, philosophers, artists, writers, and me!

Me? I’ve got the “Big Picture!” for my next book. Now all I need do is fill in the details. To do this I must enlist the part of my brain that is supremely qualified for the job: the Left hemisphere. Once engaged, I will start to look at the parts, not the whole. I will take these parts, line them up, arrange them in logical order, and piece them together to produce the whole. It’s analytical, sequential work that will no doubt take months to complete. (It’s the perfect counter-balance and repose before I embark on the glorious and torturous years I will spend in the Right hemisphere, using imagination and invention to actually bring the “Big Picture” to life; to write the book.) So armed, I begin.

I launch into some of the back-story and plot-lines: A hard-boiled, soft-hearted, misfit, with a truckload of troubles and a tragic and haunting past – a past that has left more than a few dead bodies in its wake – skips town after the gut-wrenching murder of her only friend – a homeless drunk – on the rough streets of Skid Row – a murder that thrust her straight into the murky, seedy world of sex, drugs, and greed. To escape the past, the pain, and her affection for an unavailable and happily married cop – a cop who took a bullet in the head for her – a cop who made her foolishly believe that she could fit in as well as the next guy – a cop who told her she could have something she’d never had before: love that didn’t hurt – a cop who knew entirely too much about her – she drives balls-to-the-wall – south – till she runs out of gas just outside a small town near the Mexican border – pop. 836.

Oh, joy! Oh, bliss! Oh endless possibility! It’s time to press my Left hemisphere into further action: Research. First, the Protagonist. Providentially, it just so happens that I know her well! Honey McGuinness already exists among the scores of idiosyncratic characters that live in my head. So, I move on. The small town. I start reading maps. I’m looking along the Mexican border. There are several options, and although the maps, library, and Internet provide me with copious amounts of information – something is missing, something tactile. I decide to take a trip. I explore the southern border of California: Jacumba, Calexico, Yuma. I head into Arizona: Lukeville, Nogales, and then I hit the jackpot: Bisbee – a tough little town a hop, skip, and jump from the border. I spend a couple of days at the Bisbee Inn. I observe. I walk around, eat, drink, socialize some – ask lots of questions.

By the time I leave town I know I can write about the place. I know the color of the sky, the feel of the earth. I know the shape of the people, the cadence of their voices. I know the way they walk, eat, drink, think. I move on. Back in my studio I concentrate on the man “wearing a long black coat and quoting from the Bible.” Who is he? What’s he doing in Bisbee? How will he feed the starving Honey? How will he take her down into the abyss? He’s an outsider, an outcast. He knows how to manipulate. He knows how to use sex. He’s in control of his universe. So, who is this guy? I think. Bingo! He’s the charismatic leader of a religious cult! He and his followers live on a ranch secreted in a mountainous area on the outskirts of town. Okay.

Now I’ve got to study religious cults, brainwashing, the use and mechanisms of sexual exploitation of cult members. Outstanding! (This is one of the best parts of being a writer: It provides a legitimate excuse to delve into any and all facets of life – even those that are more than a bit dodgy!) And so, I initiate contact with a religious sect just a few blocks from my studio. (As it turns out I’ve got a choice; there are several such cults in my neighborhood?!) I speak to members under the guise of possibly signing on. I attend a couple of get-togethers, and lastly an indoctrination meeting. Next I turn to the FBI for brainwashing techniques. (They are surprisingly accommodating.) As to the issue of sex, I seek out and meet several times with an author who memorialized her experiences and escape from just such a sect. (I decide to take the vicarious route on this particular issue for a host of reasons, not the least of which is that I can just hear the last question my husband asks me before packing his bags, “You did what?!”)

And so the research goes, month after month – one character, one subject at a time – until I have analyzed each part, pieced them together, and arranged them into a whole. And then one day I find myself sitting alone in my studio. Notebooks of Left hemisphere data are at my fingertips. I am now ready to draft my Right hemisphere into service, and put the story down on paper – one magical word at a time.

Of course, it’s not this black and white. There are times throughout the process that the split-brain theory doesn’t bear up. Times when the Right and Left hemispheres ooze out, spill over, burst at the seams – times when the brain works in a state of holism. But whether the hemispheres are working separately or together, there yet exists in the brain a deep, sumptuous, and seemingly bottomless reservoir of fact and fiction – science and art – upon which the writer can draw to achieve her single-minded purpose: To write. To write a story.

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Thanks for the article, I enjoyed it. I, too, have thought about the brain’s hemispheres when working on my own novel. Interesting take on it. The way I look at it is the opposite. All the work I do BEFORE I start writing is my Right brain work — I’m inventing the story, working creatively to create the characters and storyline. It’s the inventive stage. When I actually start writing, now I’m in Left brain mode. This is where I have to craft sentences and paragraphs to communicate clearly and accurately. Here i have to organize everything I created, and work with language to get the book written. Right first, then left. By the way, the story featuring Honey M. you used in the article sounds good … cant wait to read it. –LS

Hi LS —

That’s interesting. I never thought about enlisting the right brain prior to starting the actual writing. So very interesting. Thanks for your response to the article. I’ve actually gotten a few email requests to quote from it for the purpose of scientific research papers. Funny. “Threshold” is available if you want to read it. (Amazon.com etc … ) If you are of the mind, please let me know what you think. Is your work available? If so, what genre do you employ?

bk