In Search of Aimai Cristen by Phillip Good does not begin with the page above, but with this personal ad on page one:

1. The Ad

Young attractive girl, 24, searching for

love, compassion, joy from a man who can

provide financial security. Write Aimai

Cristen, Box 3689, Barb Office, 1234

University Ave, Berkeley CA 94709.

The ad is enough to pique my curiosity: a woman seeking what, I suppose, could be described as the stereotypical idea of a “perfect” man. Not only is he loving and compassionate, but he’ll be a sugar daddy. What lonely woman with no ambition of her own wouldn’t want that?

Any correspondence in a novel interests me, frankly, even if that correspondence isn’t necessarily personal and has been cast out into the world for anyone to answer. As a first page, the ad works well for me.

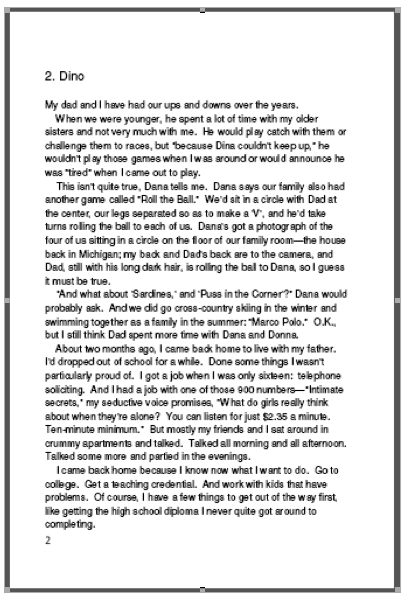

The first complete page, on the other hand, loses me a little. The first sentence, “My dad and I have had our ups and downs over the years,” is a little “eh.” Who hasn’t had ups and downs with their parents over the years? Conflict in the first sentence is effective, but giving the conflict a unique twist, something specific and in keeping with the drama between the characters, would be more effective. For example, “I’ve always hated that my father paid more attention to my siblings than he did to me” tells us exactly what the conflict is (as the narrator sees it), and we’re then curious to read in what ways the narrator was ignored, and in what way the siblings were favored.

The altered first sentence also provides some insight as we move deeper into the first full page when the narrator’s belief that her father neglects her is refuted by her sibling Dana, who offers some examples of their father spending equal time with the siblings.

“Well, O.K.,” says the narrator. “But I still think Dad spent more time with Dana and Donna.”

Were the sentence the altered one, I would expect this disagreement over time spent and would assume it to be part of the central conflict among the siblings. But, as the first sentence is originally written, I’m left wondering why I should care about the different ways siblings see the time they spent with their father. What’s special about it? What’s the “so what” of it?

I’m also left a little confused by the chapter’s title, “Dino,” followed by the mention of characters Dina, Dana, and Donna. The narrator does say she has older sisters, but how many? Are Dino and Dina and Dana all different people, or is there a typo somewhere? Without doing too much “telling,” an author could, in the case of many similar names, explain in a quick line the reason behind them. “Mom loved the Flinstones’ dinosaur and wanted us all to have a variation of its name,” for example, would eliminate some of the confusion.

With all of that said, however, I do want to keep reading. I like the way Good reveals the narrator’s sex on page one by having her mention a job she took at 16 as a phone sex worker. I like the idea of a delinquent and slacker girl—there are plenty of delinquent and slacker boys in stories, but not so many girls.

An interesting character promised, here, combined with the lure of the ad and this Aimai person. And when I scroll-flip to pages seven and eight, I see an interesting and powerful relationship between daughter and father being explored.

An editor once told me the first three chapters of a novel can usually safely be cut from a just-finished manuscript. I’m starting to believe he’s right; I’m finding in many of these first pages I’m reading that the real story often begins long after page one. It certainly seems to be true in this case.

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

Leave A Comment