The conversation with a prospective literary agency should go something like this:

“Would you like us to sell your book to a major publisher?”

“Yes, please.”

“Are you willing to make a fair number of changes to your novel to make it marketable to major publishers?”

“Absolutely yes.”

Three months ago—two months ago, one week ago—I’d have wanted to be in the position to have to answer that question. “Are you willing to make a fair number of changes to your novel to make it marketable to major publishers?” I’d have been envious of anyone else in that position. And I’d have been bitterly annoyed by anyone daring to discuss that “dilemma” as if it were oh so difficult poor baby to have to decide whether to let a literary agency take on their novel.

But now?

Now I have to decide whether I’m willing to make a fair number of changes to my novel in order to make it marketable to major publishers.

Do I want an agent, this agent, bad enough to change my book?

I don’t know, yet, what the changes are. But I know I won’t get that agent if I don’t want to make those changes. If I don’t like their suggestions I could try other agencies, sure…but I’ve already been trying—by marketing the book I self-published—for a couple of years. What if this is it?

I’d be a fool to deny this opportunity.

“Do whatever it takes to get your foot in the door,” said a writer friend whose whole body is in there.

“Let them make the changes,” said another friend. “Once you’ve published a few more books, you can re-release the first one the way it was originally written. You know, like Stephen King.”

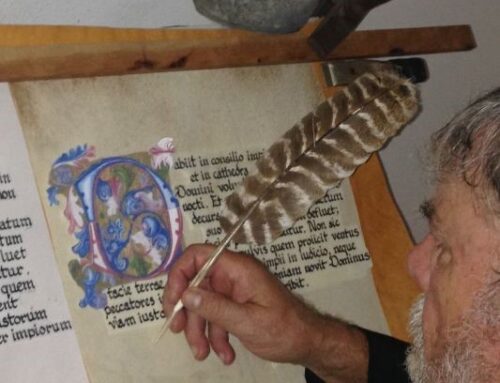

But here’s the thing (and this is not unique or special, but it’s the thing): I love my book. Every character, every character arc, every scene, every argument, every relationship, and every description was written the way it was to communicate something very specific about a singular experience in the rawest, most honest, and most effective way I knew how. Edits and revisions were done painstakingly. Obsessively.

Since self-publishing, I’ve found a typo or two in the book, and probably a page or two that could stand to go. Some scenes that would benefit from tightening. But those are minor changes. Practically cosmetic.

The agency did not say it wanted to make “cosmetic” changes. Nor did it use the word “minor.”

Since the communication with this prospective agency, I’ve been waking up earlier than usual. What changes could they mean? Changes in character relationships? Do they want to eliminate a character? What if they want to set it in a different time period, like sixty years in the future? What if the changes they want me to make include an alteration of my very voice, undoing the basic plot line, taking out every third “the,” and giving me a new name because mine isn’t author-y?

Would I say yes to get my foot in the door?

Sometimes I’m amused when people say writing is an art. I agree with them, of course, but what’s funny about it is that as much of an art as it may be, it’s not really respected in quite the same way as, say, painting. Or sculpting. Art galleries don’t take a painting from the artist before the opening and add a blue brushstroke here, a gold box there. Sculptures aren’t shaved, painted, or chipped away at by Sculpting Editors to change the shape of a curve. Art by artists is accepted as is, or it isn’t.

The same doesn’t hold true for writing. First the agency edits, and then the publisher edits. The book on the bookshelf is rarely the sole creation of the writer whose name is on the binding. If anything, novel writing is a collaborative art.

Unless you self-publish.

In its current incarnation, my book is exactly as I intended it. Mine, mine, mine. It is the most important thing I have ever done, the achievement of which I’m most proud. It is, at the risk of being trite, my baby. And it’s disturbing to hear someone say they want to change my baby.

But.

I really, really want to be published. I mean, really.

“You already have your book out there the way it is, and people have read it and liked it,” my best friend told me. “When you put out a different version, that original version will still exist.”

True. But. My name would be on the new version, too—and that new version would have to be something I’d feel good about having my name on, something I could honestly claim I’d have written myself, even without editorial urging, if only I’d thought of it first.

Or would it?

I wonder about writers like Carlos Castaneda, Tom Robbins, Douglas Adams, and Kurt Vonnegut, and what their original, unedited manuscripts looked like. How many compromises did they have to make? However many or however few, look at them now. Book after book on bookstore shelves. They lived, or are living, writers’ lives.

The fortune in my cookie tonight—no kidding—read, “The star of riches is shining upon you.” I know getting an agent doesn’t mean I’ll end up like Adams or Vonnegut. It doesn’t mean I’ll make a living writing, or even that I’ll be guaranteed a publisher. Getting an agent does, however, mean having a shot at that writer’s life. And the truth is that agents and editors aren’t stupid. They don’t destroy writing; they better it. They want to sell it just like writers do. They may be less personally attached to the work, but they’re a business, and businesses aim to succeed. Chances are I’ll be excited by many of their ideas.

Even so…

Tomorrow morning, I’ll no doubt wake up wondering about those editorial suggestions. What if they want to make a revision that changes the fundamental meaning of the book? What if they aren’t open to discussion about something I simply can’t agree to change?

How bad do I want it?

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

My observation here is that agents are interested in the easy sale and tend to chase the market. This agent probably wants you to follow the lead of of the latest best-seller. This is how we get so much bad fiction published. I am a great believer in the ‘droit morale”; the right of the author to control the work.

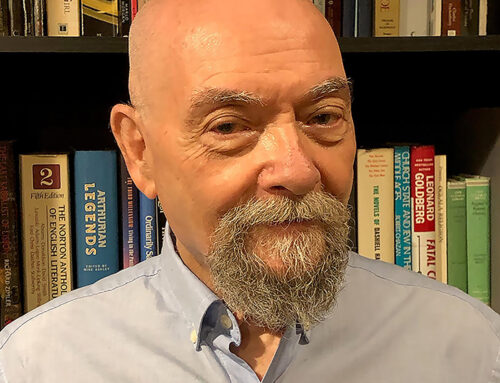

The problem with agents these days is that too many of them act as writers are working for them rather than the other way around. Ernest Hemingway never had an agent. He did have a great editor in Maxwell Perkins, who worked with him on the final form, but that was after Mr. Perkins had skin in the game in the form of a big advance. That kind of collaboration makes sense. Rewriting to satisfy an agent’s guess work about what might sell doesn’t. And it can make you crazy. The policy of large publishing houses that they will only accept work submitted by an agent simply gives them too much power and hurts publishing. They need to rethink this.

On the other hand, self publishing becomes a more viable alternative. If you think you have a good book, then put it out yourself.

I’ve had this sort of response from more than one agent, and declined to make the changes. It cost me representation, but I don’t think it would have worked out with an agent who had such a different idea from me of the book’s direction.

I have, however, been known to change short stories for editors …

Look, I am all for sticking to your guns on these matters. But the fact of the matter is that if you want to break into this highly competitive industry, then compromises are not only a suggestion, they are a motherfucking necessity. If the author of this article is who I am pretty sure it is, then I don’t need to beat this point into the ground. BUT–and this is a great flipside to that reality–the tide is turning.

As this article in the latest issue of Time magazine explicitly points out (http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1873122,00.html?xid=rss-topstories-cnnpartner), more and more the publishing industry as we know it is being forced to change gears and the former approach to finding new authors is becoming irrelevent. No longer will the gate-keepers to Big Publishing be agencies–it will be readers who have discovered our books through some form of self-publishing. This is a reality I have fought for in the three years since my novel, futureproof, was first self-published. Fuck editorial reviews in newspapers and magazines. I don’t pay the slightest attention to any of these ‘professional’ critics. I’ve gotten some nice reviews from these avenues but I dont give a damn about the reaction from some failed writer (they say all art critics are really just failed artists themselves). The critiques I truly care about are those of the people who are reading my novel when they could be spending that time not only reading something else, but doing anything else as well. Look at my myspace page (myspace.com/nfrankdaniels). The reviews I have highlighted there are those by other writers and the readers themselves. THESE are the people who really matter. This industry is becoming quickly democratized. The entire paradigm is shifting. Everyone will benefit from this. Because after all, if the ‘common’ book consumer doesn’t like your writing then it doesnt matter what some agent or editor or critic, positive or not. You might get a book published but if nobody’s buying, you are far less likely to see your second book in print.

HOWEVER, it must also be taken into consideration that it is incredibly trying to find an audience when you are self-published. You have no publicist. You have no bookstores ordering thousands of copies. You are alone and must fill every role yourself. My novel drops from Harper Perennial tomorrow. It will be in every Barnes & Noble. It will be in every Urban Outfitters. This isn’t a position you will be in if you’ve only self-published. So my advice is to hear this perspective agent out on his/her suggestions and stop worrying about it now. Decide what you can and cannot do and still sleep at night. But for Christ’s sake, don’t shoot yourself in the foot. You never know when you might have such an opportunity again. And if you’re in this for the long haul, I GUARANTEE that you will write more and better books than your first one. It’s inevitable. The juice is worth the squeeze.

I’ve had agents. Their solution to making a sale was to chase the market. The problem with that is the market evolves and you never catch up. Having done sales work, and lots of it, I understand where they are coming from. They are on straight commission — in California, by law — and they want the most money for the least time spent…and you are not their only client. If you are just starting out and don’t know much, they want to boss you rather than represent you, but they can’t do what you do, of they would be writers themselves. Every writer I know has the repeated phenomena of someone approaching them and saying “Hey, I’ve got a great idea for you!”. Meaning you do all the work and they get a piece, either as agent or collaborator. Equity without the sweat.

And they get it wrong more than they get it right, like the agent who told Tony Hillerman he’d have to get rid of “all that Indian stuff” if he wanted to sell mysteries. The pressures to compromise your vision can be intense. Resisting them is where you find out if you’re a writer or a hack or, just a typist.

The current system gives agents too much power. There’s no more direct submission, even at small presses. “Over the transom” is a thing of the past because no one hires interns anymore to read the stuff. I am convinced that the bad rap against self publishing is something put around by the agenting community to preserve their power. I’ve seen this at science fiction conventions, where some people are almost hysterical in their insistence that the One True Path to success is to get an agent and take direction. This in a community that invented fan fiction and where every fan wants to be a writer! Fan fiction is training wheels writing.

Self publishing, done right, is a lot of work and involves skill sets that most writers don’t possess. There are, however,, work-arounds and one of the purposes of this site is to show you alternatives.

Anyone can publish a book now. But the book has to be competitive as a product in the marketplace to succeed. That means it has to look better than the product from a mainstream publisher. Sadly, they keep lowering the bar. Editing, fact checking and other small attentions to detail seem to be ignored. In the end you may well be better off doing it yourself. No one will love your book like you do.

I believe in “kaizan”, which is a Japanese word meaning “continuous improvement”. This is why you might do 15 drafts of a novel to get it just right. I also believe in the motto of the old Soviet space program. “The perfect is the enemy of the good”.

Electronic publishing gives us a low-cost way to beta-test product. E-books area nicvhe market and always will be, but “niche” does not mean “small”. Smashwords.com, founded by a novelist, puts your work into all of the electronic formats for distribution and takes only15% of the net plus some transmission fees. You set the price and your work can be sold, or given away as you direct. You can revise. This may be part of the future business model for writers. Direct to the audience, as the Time Magazine article said. But that’s just the beginning. The larger audience still wants a printed edition and probably always will.

My answer to “Would you be willing to make a fair amount of changes” would be, “What did you have in mind?”

If the agent made suggestions that I felt strengthened the writing, great. If it became clear that this person had no sense of the book’s unique strengths, then no.

There’s a great essay about how to become a writer by Jennifer Weiner. She answers your agent question in step #8.