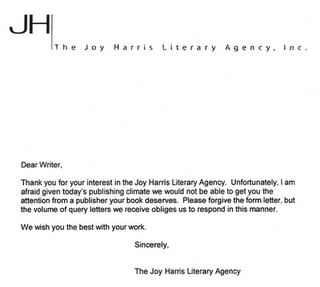

And it is in this gluttonous – perchance self-delusional – state that the writer dares to think the work all-out brilliant – surely worthy of representation and publication. So convinced, the intrepid writer takes that fateful flying leap into the duchy of literary agents and publishers – the very locus of the infamous Mr. Rebuffer, and his Gongoresque rejectionists-in-training. The writer includes the compulsory SASE with each manuscript, though certain none will be returned. Then the writer waits. Assuming that the odds of enlisting an agent and getting published are working against the writer, there are two scenarios afoot: Immediate rejection or delayed rejection. Either way, it hurts – literally.

In October 2003, a UCLA-led team of psychologists reported the results of their study on “rejection” and its effects on the brain. Conventional wisdom has long held that rejection is an emotion that is technically unquantifiable. However, the UCLA-led team proved otherwise. They concluded that “rejection” does, in fact, register in the brain! And further, that the mechanism by which this occurs is identical to the experience of physical pain!

(Aside: If you’re wondering how on earth they measured “rejection” in the brain, their methods were quite ingenious. They attached doohickeys to several people – their test subjects – then had the group play ball together. After several games had been played, the researchers singled out specific test subjects and removed them from the game. Eventually, these “rejects” started to feel “rejected” . . . which moved the needle on the brain-registering gizmo that was hooked up to the doohickeys that were hooked up to the “rejects.” Ergo, their conclusion.) (Aside #2: Having made this discovery, the scientists engaged the essential question: “Why” does rejection hurt? Their concluding theory is that “rejection” affects the brain because it is deeply-rooted in our DNA. Long ago, mammals relied on social bonds to survive. Broken social bonds put survival in peril. Mammals therefore feared any diminishing of these bonds. And this congenital fear is so entrenched that today’s mammals still see any form of exclusion from social connection as a direct physical threat. Interesting. In fairness, and in counter-balance, theology may offer a more divine answer to this question.)

Now, knowing that the pain of rejection is technically physical, the writer can take a new approach to “healing.” With an “officially recognized” injury, the writer has legitimate reason to:

- Take time off from writing. (I recommend setting a deadline. Say, a couple of weeks – one month tops.)

- Stop feeling histrionic. There is no more “over” in “over-reaction.”

- Stop the self-reproach. You are justifiably sick, lethargic, depressed, hopeless, bitter, and angry. (Warning: Do not “actually” take your anger out on Mr. Rebuffer or his myrmidons. This would be a Big Huge Mistake.)

- Luxuriate in self-pity. (Sad music is an expeditious and freely accessible portico into this seemingly bottomless abyss. Suggestions: ‘Hurt’ by Johnny Cash or Nine Inch Nails. ‘Concrete Angel’ by Martina McBride. ‘Hallelujah’ by Jeff Buckley. ‘Back to Black’ by Amy Winehouse. ‘The Promise’ by Tracy Chapman. ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’ by Sinead O’Connor. ‘In the Real World’ by Roy Orbison. ‘Gloomy Sunday’ by Billie Holiday. ‘Drugs Don’t Work’ by The Verve. ‘Lonely Day’ by Systems of a Down. ‘Creep’ by Radiohead.)

When the writer tires of these indulgences, it’s time to plunge into phase two – the restoration of fortitude! In this stage the writer should:

- Listen to positive, empowering music. (Suggestions: ‘So What’ by Pink. ‘What a Wonderful World’ by Louis Armstrong. ‘Three Little Birds’ by Bob Marley. ‘Dance To The Music’ by Sly & The Family Stone. ‘I Will Survive’ by Gloria Gaynor. Anything by Tina Turner.)

- Bear in mind the following facts: Anthony Burgess published his first novel at age 39. Henry Miller published his first novel at age 44. Raymond Chandler published his first short story at 45 and his first novel at 51. Charles Bukowski published his first novel at age 49. Marquis de Sade published his first novel at 51. Richard Adam published his bestseller at 52. Mary Wesley published her first novel at age 70. She continued to write at least one best-selling novel a year for the next two decades. Harriet Doeer published her first novel at age 73. Her novel went on to win the National Book Award. And, if the foregoing fails to elevate the spirit, consider this: Emily Dickinson was first published four years “after” her death.

- Remember that the depths which we experience one emotion is in equal measure to the heights which we experience its opposite.

- Shake off the dust, and get back to work!

Despite the technical findings and a careful execution of the above protocol, the hurt of rejection is not likely to heal as neatly as a broken bone. And perhaps there’s good reason for this – something altogether unscientific. Rejection doesn’t just build stamina – a quality that no writer hoping for longevity and success can afford to sacrifice. It also gives the smart writer a valuable opportunity to look at the work – dispassionately and critically. Viewing the work through a judicious lens, the writer may conclude that the Rebuffers were totally off the mark. Or, the writer may concede that they had a point. Either way, the next course for the writer is explicit: Carry on the process of sending the unchanged manuscript out to targeted agents and publishers – or, rewrite, and then resume the quest – all the while, steeling for the next round.

In the end, though physical and emotional pain may technically register through identical mechanism, “rejection” may, in fact, serve the heroic writer well . . . by strengthening both heart . . . and mind.

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

One more song: “I Hate Everything About You” by Three Days Grace. 🙂