The general points made by both author and reviewer seem to be (1) that, in the post-World War II era, college writing programs and writing workshops have proliferated, (2) that innumerable writers have been involved in these programs as students, teachers, or both, and (3) that American writing has risen to new heights because of them. “The rise of the creative-writing program,” McGurl is quoted as saying, “stands as the most important event in postwar American literary history.” Impressive statistics lend their weight to the argument: from a handful of programs in 1945, the number has risen to “eight hundred and twenty two” degree programs. Thirty-seven schools, it is said, now offer a Ph.D. in Creative Writing – not to mention a growing list of online PHD programs. The argument is buttressed by long lists of writers who attended various programs, met other writers who are also listed as being in attendance at the time, and then went on to teach at still other programs, where they met other writers, who taught other writers, who . . . and the beat goes on.

After a good deal of this, doubts and questions begin to insinuate themselves into the mind of a reader. If there are “eight hundred and twenty-two degree programs” shouldn’t there be at least eight hundred and twenty-two distinguished writers who teach in these programs? But the names of distinguished writers listed as associated with writing programs do not (I think—I gave up counting) amount to anywhere near that number. What do the graduates of all these programs do for a living? They teach, of course, some in famous programs and many in less famous ones. Many teach part-time in an academic market where there are far more aspirants for full-time jobs than there are funds to support them. Most writers earn nowhere near the annual incomes of the headliners and bestsellers among them: annual incomes for writers when figures are given either as averages or medians generally amount to no more than $40,000—when there is any income at all. On this point the dues structure of the Authors Guild is instructive: dues are assessed according to income from writing, and the first two categories, of four, are for writers who earn, respectively, less than $25,000 and $50,000. Try rising a family on that. A part-time teaching position begins to look pretty good. Can it be that the proliferation of writing programs is partly the response to the need for graduates of writing programs to find gainful employment while they work on books that don’t find publication, or that pay very little when they are published?

Let’s return to the question of quality. By what measure is creative writing better now than it was before1945? Many great American writers of the nineteenth century had little or no college and no tutoring in writer’s workshops. From 1900 to 1945, colleges and workshops continued to remain outside of the lives of many of our best writers. The New Yorker essay makes the point that writers seek out good writing and commonly associate with other writers, and as far as that is true, it used to be true in earlier times as well. In an era when many more people attend college than their ancestors did, it follows that those who love literature will take literature classes and that those who aspire to write will enroll in creative writing classes. It is also possible that with a total population of the United States vastly larger than it once was we now have more potential for the emergence of creative excellence. None of this means that if there is an expansion of good writing today the programs have been responsible. In the early years after 1945, Freshman English classes commonly included a unit on logical thinking that featured an explanation of the post hoc ergo propter hoc (“after this, therefore because of this”) fallacy, and this seems an occasion to invoke again that kind of intellectual rigor. Yes, classes in creative writing have expanded and have enrolled more students than they used to. But it does not clearly follow that better writing, if it exists now, is the result of that development.

Moreover, the evidence given in The New Yorker does not come close to supporting the idea that the writers and programs mentioned have produced a level of writing that can be compared with the work of the great writers of America’s past. On the contrary, a good argument can be made that writing programs, whatever successes they may have had in increasing the annual production of books, have not contributed much to the production of lasting literature.

A list of prose writers of our time who might be measured with some success against the best writers of earlier periods would include James Baldwin, Saul Bellow, Raymond Carver, John Cheever, Don DeLillo, Ralph Ellison, Louise Erdrich, Jhumper Lahiri, Norman Mailer, Bernard Malamud, Toni Morison, Vladimir Nabokov, Joyce Carol Oates, Thomas Pynchon, Philip Roth, I. B. Singer, Anne Tyler, John Updike, and Eudora Welty. Most of these names are not mentioned in the lists of authors trumpeted in The New Yorker as proof of the success of creative writing classes and most have had little or nothing to do with such programs except for occasional guest appearances that came after their success, not before it. Yet these are the contemporary writers most frequently taught in present-day American literature classes and they are the ones whose works can be most easily compared in strength and beauty to the works of Hawthorne, Melville, James, Twain, Wharton, Hemingway, Faulkner and others of our illustrious past. Perhaps the best that can be said for creative writing programs is that they do little to hurt anybody and may possibly inspire a few to find the genius that lies within.

Get an Editorial Review | Get Amazon Sales & Reviews | Get Edited | Get Beta Readers | Enter the SPR Book Awards | Other Marketing Services

I have a degree in creative writing and journalism. In the first semester of my senior year creative writing classes, my professor said (after the first couple of assignments), “You already have an A in my class. I can’t teach you anything. I’d appreciate it if you’d still come to class and turn in the assignments, though, because I love your work.” My second semester, the professor hated everything I wrote and I was lucky to squeak out a C (and that was after a direct confrontation that should never have happened).

I would submit that you cannot teach creative writing effectively without demanding the student conform to what your idea of “good” is (and probably very narrow at that) and that anything other than that is therefore “bad,” thus, a mentoring relationship may be simply an experiment in cloning. But bouncing from professor to professor may not get you any better instruction when one loves what you write and the next hates it.

The sticky wicket is the word “creative.” You can teach Comp 101 and some people are never going to get it, but likely those people don’t have a story in ’em. If they do, fine. Teach them craft and see if they get it. If not, oh well. After being in critique groups for years and stopped when one of those types of people never got it, I decided I wasn’t going to waste my time.

But what if you come across a fairly competent writer who writes fiction but has no real story? I ran into a bunch of those in my degree course…

When I was earning my MA in English some years ago, I was enrolled at a university that also had a substantial MFA in Creative Writing program, so I spent a couple of years watching how that program worked without being a part of it. I was (and still am) of the opinion that such programs are a complete waste of time, but what’s fascinating is that all of the MFA students I talked to during those years agreed with me. I never met a single person who believed that the workshops he was going to was essential to becoming a successful writer. And yet, they all stayed enrolled in the program. Odd.

Another very interesting thing that I noticed about the MFA program was that none of the fiction writers in the program were interested in becoming “genre” writers. From what I could tell, there weren’t any budding mystery writers or romance writers or YA writers. No, instead, they were all determined to write and publish only “literary” fiction. They were all convinced that they were going to be the next James Joyce or Jane Austen — which of course also led them to develop very high opinions of themselves. It was kind of funny, really. I also noticed that almost all of the MFA students also had written at least one movie screenplay. One fellow, after getting into a fistfight with a freshman student during his office hours, even dropped out of the program and moved to Hollywood to “make it big.” I never heard from him again.

I’m MFA Iowa Writers Workshop in Fiction. That’s supposedly the Gold Standard. With all due respect to Dr. Perkins (and I haven’t read the New Yorker article yet. Just got my copy today) the point of taking an MFA is not to gain reputation or get published or even get a teaching position. The latter universally require a Ph.D be in hand now just to be considered. The reason for going to a MFA program is (1) to prove that you are a good enough writer to get in the program. Iowa rejects 95% of all applicants and (2) study with writers that you admire, who have enjoyed some success and can give you guidance. There are about 50 times more graduates than teaching jobs, so you really do need a PhD. To get a PhD you have to deal with a heavy load of cultural and critical theory, none of which will make you a better writer. That’s like learning auto mechanics to get a drivers license; one has very little to do with the other. (A true educator will want you to do that, of course, because utility and learning are not on the same plane but why take chances. Cram it all in.)

I studied with writers who were considered among the literary giants of their day. Vance Bourjaily, Jack Leggett, and Robert Anderson were my thesis committee. Anderson taught me to write screenplays. If these names are unfamiliar, that just shows that literary glory is very transient. My other instructors included William Price Fox and, yes, Raymond Carver, who I endured for a semester of drunken antics and no teaching whatsoever. I’m not sure what he was doing there since he’d never completed his own degree, but he had a big rep and that sufficed.

There were genre writers in the program. Joe Haldeman was a classmate of mine. James Crumbly had been there a few years before. The program is supposed to give you a couple of years to work on your stuff and talk to other writers about writing. It’s a peer-review feedback class where people talk about story, character and style,; things which most PhDs comprehend dimly if at all.

As for the pretensions of MFA students, that too is part of the program. You already know you’re very talented because you are there. Part of the process is to build your confidence and help you discover your voice. That’s not done by being kind or gentle, but by being pretty tough. Those classes could make “Survivor” look like a tea party. But getting your work out to an audience requires a kind of mental toughness. If you don’t believe in yourself, who will believe in you? By your very presence you’ve already proven you can write; now you have to prove you can write better than anyone else. This is not a task for the shy and retiring. It requires a cast-iron ego and nerves of titanium.

These programs do not guarantee publication or great success or critical acclaim. They give you the tools, but you must do the work.

Ambrose Bierce’s “Little Johnny” column once had Johnny saying “I ast my dad how come the papers’re always printin people’s pomes, and he sez ‘So the authers c’n check ’em fer mistakes.'”

So much for my degree in Creative Writing, Skidmore College, a long time ago; in fact I made the term up afterward. It was one of the early do-it-yourself college programs, called University Without Walls. Didn’t want a perfectly good scholarship to go to waste. Like most of you, I am fully qualified to be appreciated as posthumously as anybody. Let us bow our heads and swear to be content.

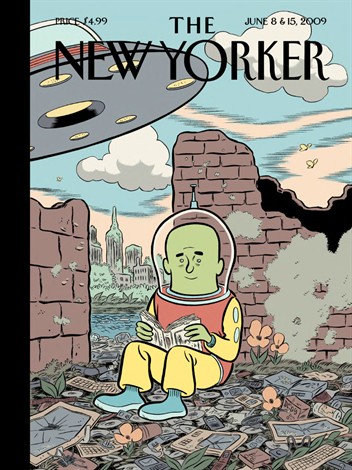

I have a treasured old friend. She’s now 103 and still going. James Thurber put the very first copy of the New Yorker in her dainty hands for her 21st birthday. She was a dancer from a highly musical family, who palled around with Thurber and the Algonquin Table people. “I still don’t know if I liked Dorothy Parker,” she said once. She seemed introverted and kind of sneaky. This lady, I am proud to say, was very fond of my writing — until I wrote about her.

I think that good writin’ can be taught, and this is no small thing. Yet “teaching creativity” resembles an oxymoron; after all, learning the rules is a rote matter. Creativity is a matter of wresting out one’s mythology from the jungles of his psyche. It is an endless living thing. If it is not, why write? If it is, a good background in literacy will do.

I started that New Yorker article, but flipped past it after assessing the tone. It registered as BS. Apparently, I gauged correctly.

The problem starts with the first word of the phrase, “creative.” How do you teach “creative”? You can teach writing to some extent, but if the person has no flair or passion, the baseline of competence should be a goal. For those with the mojo, a teacher can be problematic.

I remember taking a college creative writing course — only one. It was a joke. Even at that age, I had the feeling I could write circles around the instructor. Maybe it was the arrogance of youth, but I don’t think so. At the same time, Francine Prose, a writer with a true gift, was teaching another course I was taking, and I was in awe. That lady can write!

There’s an illusion that anything can be taught. Sorry, but nature beats nurture at almost every junction of the two. Nurture can reveal talent but it can’t generate talent. And since creative writing courses are not about revealing talent but teaching someone else’s idiosyncratic technique, they don’t work.

Good catch! The New Yorker article was BS.

Andrew:

Agreed: It can’t be taught. It can be guided and improved. Which is what MFA programs are designed to do. It’s apprenticeship.